(Post-)Colonial Biography

Assessment Production Details

Developer: Amanda Mingail Shubert Contact

Peer Reviewer: Sarah Ohmer

Assessment Guide: Pearl Chaozon Bauer Contact

Copyeditor: H Fogarty

Webpage Developer: Adrian S. Wisnicki

Associated Assessment: Riya Das, “Recovering and Reevaluating Anglophone Writers”

Cluster Title: Widening the Empire

Publication Date: 2023

Assessment Overview

Download the peer-reviewed assessment: PDF | Word

I created the assessment “(Post-)Colonial Biography” for my undergraduate course “Women’s Writing and the Global Nineteenth-Century,” which I taught for the first time in Fall 2022 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison). This advanced course, which enrolls a mixture of English majors and interested non-majors, asks how nineteenth-century women writers answered the question “What does it mean to be free?” Students read memoirs, fiction, essays, and speeches by women writers across the British Empire. Lectures, discussions, and assignments invite students to use textual analysis to examine how these writers imagined, agitated for, and enacted liberation. They find that women writers of different backgrounds, identities, and positionalities can define freedom in radically different ways.

I designed “(Post-)Colonial Biography” for this course, as well as for use in other courses I teach on the literature and visual culture of the British Empire, because I want students to think about the experience of colonialism as something that they share with the writers on the syllabus. Writers like Pandita Ramabai, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, Mary Prince, and Susanna Moodie are aware of themselves as actors within a colonial scene and the way that the horizons of opportunity and experience for their lives are conditioned by empire. What would it look like for my students – descended from colonizers and from colonized people and participants in settler colonialism who are learning on indigenous land – to develop a similar awareness?

The course is designed to teach students to closely analyze themes of liberation in the works we study within the context of the history of empire. This requires them to adopt methods of intersectional critique, observing how the power asymmetries created by empire and its legacies of white supremacy, slavery, and colonialism shape the different ways that British, Caribbean, South Asian, U.S., and Canadian settler-colonial women demand and envision freedom for themselves and for their communities. To this effect, the course is divided into three units:

- Unit 1, “Freedom from Patriarchy,” explores how women writers advocated for female emancipation and education in patriarchal societies. We focus on the essays of three feminist women, Mary Wollstonecraft (Britain), Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (India), and Pandita Ramabai (India), but we also read short stories by Olive Schreiner and Charlotte Perkins Gilman that address themes of women’s oppression and liberation.

- Unit 2, “Freedom from Slavery,” focuses on two memoirs by formerly enslaved women, The History of Mary Prince and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, to consider how these writers portray the intersectional oppressions of colonialism, chattel slavery, and patriarchy. To cap off this section, we read the opening chapters of Jane Eyre, asking how this narrative of white female emancipation appropriates the literary conventions of the slave narrative.1

- Unit 3, “Freedom to Move,” addresses excerpts from Susanna Moodie’s Roughing it in the Bush, a settler-colonial pioneer narrative considered a feminist classic in Canada, to ask how white female self-determination in the settler colony not only enacts but also constitutes itself through violence against indigenous communities.

I introduce “(Post-)Colonial Biography” at the end of Unit 3 to move students from a historically and culturally specific analysis of nineteenth-century empire to a presentist analysis of the effects of empire on their own lives today. I do this by asking them to write a biographical essay or create a short biographical video of someone or something they care about that is connected to European or U.S. empires. Four prompts are available, each directing students to create a different form of biography:

- Option 1: Students interview someone they love, such as an elder family member or a friend, who experienced British colonialism or neo- or post-coloniality.

- Option 2: Students write an autobiography, investigating how their own lives are shaped by British or U.S. imperialism.

- Option 3: Students consider how they participate in U.S. settler colonialism by researching the history of the Ho-Chunk people whose land UW-Madison and the surrounding Madison, WI area occupies.

- Option 4: Students write a biography of a colonial commodity, like tea or chocolate, or a work of art made by an artist from a former British colony or commonwealth country, like Rihanna’s Anti.

The awkward punctuation of my title – (post-)colonial – registers the multiple relations to empire that students might discover. These prompts are available to all students, including white U.S.-born students, but I hope that they will empower students of color and students from immigrant families to examine their own family experiences of post/coloniality.

I have explained how I situate this assignment in my syllabus for “Women Writers and the Global Nineteenth Century,” but I want to address the role that it can play in Victorian Studies curricula more broadly. “(Post-)Colonial Biography” invites students to research, reflect upon, and explain to others how the effects of empire are felt in the present. The assignment is a response to an issue that I come up against regularly when I teach empire, colonialism, and the history of slavery: the tendency of my students to distance themselves from the course material by reflecting on how such crimes against humanity happened “back then,” before “we” learned that such things were wrong.

This gesture reflects, in part, the understandable but erroneous assumption that history belongs to the past or that history itself is progressivist. For example, after reading Shashi Tharoor’s vivid description of Britain’s colonization of India in Inglorious Empire, one student exclaimed in genuine anger and confusion, “How could this have been allowed to happen?” I was grateful for my student’s moral outrage. But we were having this conversation on the ancestral land of the Ho-Chunk people in September 2021, shortly after President Biden pulled U.S. troops out of Afghanistan after a 20-year occupation. I had opened my students’ eyes to the western history of colonialism, but they were not yet able to think of colonialism as a living history, one that is ongoing.

In this regard, the assignment is meant for any course in Victorian Studies that addresses empire or colonialism. I have designed it with my particular students and institution in mind, in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, but with adjustments it can translate across national and institutional contexts. UW-Madison is a predominantly white institution (PWI). The majority of enrolled students identify as white and are Wisconsin natives, and most are women. However, the course also enrolls students from across the country, including international and exchange students, and includes a contingent of students of color, primarily of Asian descent. Likely because of the title and description, more women of color and immigrant students have enrolled in this course than in the typical nineteenth-century literature courses that I teach: in Fall 2022 when I taught this course, I had students who were born in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China.

I can imagine this assignment working well at a variety of kinds of institutions in the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, and other Commonwealth countries. Instructors at other PWIs whose courses enroll primarily white students may like to invite their students to research the colonial origins of a campus building they frequent or a cultural institution built from the profits of chattel slavery. Instructors at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) or minority-serving institutions (MSIs) in the U.S. can similarly design prompts that invite students to research how colonial history shaped family histories of enslavement, displacement, migration, community building, language learning, and resistance.

Built into the assignment is my community-based research and writing pedagogy, which asks students to create work that teaches one another something they have learned. The assignment is also designed with contract grading in mind. Because other instructors may not share these practices, let me say a few words about how they work and why I have chosen them. I have written in the past about my selective use of contract grading to promote equity and engaged learning in a year of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the success of this experiment, I now exclusively use labor-based contract grading. All assignments are graded complete/incomplete, with students receiving final grades based on the number of assignments they have completed over the course of the semester. This frees students to experiment and take risks without anxiety.2

I find that my students thrive when labor-based grading is paired with a horizontal knowledge-sharing ethos. For example, “(Post-)Colonial Biography” asks groups of four students to read or watch each other’s work. They then complete a peer-review worksheet for each project to reflect on what they learned and to analyze the quality of research and analysis. After this, students meet up outside of class for an informal conversation in which they share insights and feedback. Finally, they submit a brief reflection on what they learned from the process as a whole. This kind of scaffolding means that students’ social and educational responsibility to one another and to the collective project of learning is supported by the work of researching, writing, reading, and thinking critically.

While contract grading and community-based pedagogy may not be possible in all contexts, it is imperative that assignments that ask students to engage with antiracist and anticolonial content are assessed in ways that do not replicate the racist and colonial assumptions underpinning many traditional grading practices. I urge instructors to thoughtfully consider how to respond to and assess their learning objectives without passing judgement on students’ personal reflections or experiences.

- Julia Sun-Joo Lee argues that Jane Eyre is modeled on slave narratives in “The Slave Narrative of Jane Eyre,” in The American Slave Narrative and the Victorian Novel (Oxford UP, 2010): 25-52. Back to text

- For models of grading contracts, see Asao B. Inoue “Community-Based Assessment Pedagogy,” Assessing Writing (Vol. 9, no. 3), 2005, pp. 208-38 and Jane Danielewicz and Peter Elbow, “A Unilateral Grading Contract to Improve Learning and Teaching,” College Composition and Communication (Vol. 61, no. 2), Dec. 2009, pp. 244-68. Back to text

Developer Biography

Amanda Mingail Shubert is Lecturer of English and Film Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she teaches courses on nineteenth-century British and Anglophone literature, world cinema, and the literature and visual culture of empire. She is the author of Seeing Things: Virtual Aesthetics in Victorian Culture, forthcoming from Cornell University Press, and has published essays in Victorian Studies, Victorian Literature and Culture, and Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies. Her current research is supported by grants and fellowships from the American Council of Learned Societies and the American Philosophical Society.

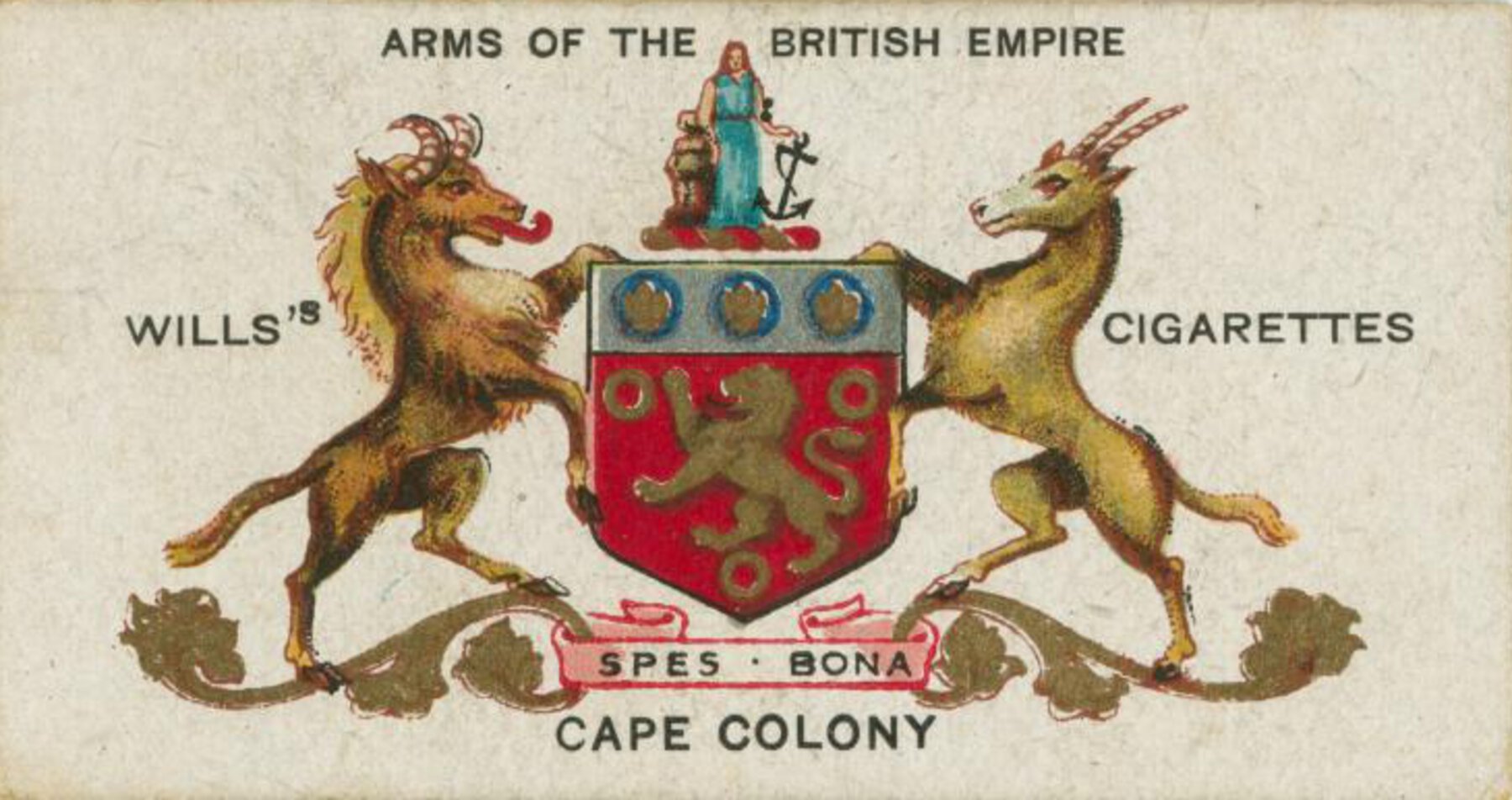

Tile/Header Image Caption

W.D. & H.O. Wills. Cape Colony. [early twentieth century]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections, b15262620. “The copyright and related rights status of this item has been reviewed by The New York Public Library, but we were unable to make a conclusive determination as to the copyright status of the item. You are free to use this Item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use.”

Page/Assessment Citation (MLA)

Amanda Mingail Shubert, dev. “(Post-)Colonial Biography.” Sarah Ohmer, peer rev.; Pearl Chaozon Bauer, assess. guide; H Fogarty, copyed. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2023, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/assessments/(post-)colonial_biography.html.