Recovering and Reevaluating Anglophone Writers

Assessment Production Details

Developer: Riya Das Contact

Peer Reviewer: Sarah Ohmer

Assessment Guide: Adrian S. Wisnicki Contact

Copyeditor: H Fogarty

Webpage Developers: Ava Bindas; Kristen Layne Figgins; Adrian S. Wisnicki

Associated Assessment: Amanda Shubert, “(Post-)Colonial Biography”

Cluster Theme: Widening the Empire

Publication Date: 2023

Assessment Overview

Download the peer-reviewed assessment: PDF | Word

Note: The assessment included here and under discussion below comes from my “British Literature II” syllabus, which is also published by Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom in the “Beyond Victorian Literature” syllabus cluster.

I developed an assessment titled “The British Literary Profile Project” (BLPP) for my intermediate survey course, “British Literature II,” which covers literature from the neoclassical period to the present. I teach this course at Prairie View A&M University, a public Historically Black University. The class size for the course was capped at twenty-five students, enabling me to teach the course in the style of a seminar. A majority of my students were first-generation university students, with a mixture of majors in English and other fields. For this assessment and the course as a whole, I required no prior knowledge of British literature/history and offered relevant contextual/historical information through the course content.

My institution recently attained the R2 Carnegie Classification, one of only ten Historically Black Colleges and Universities to have earned this status. In keeping with the scholarly expectations of this designation, my pedagogy is focused on practices that elevate BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and other vulnerably-positioned students through professionalization, mentorship, and knowledge transfer/creation opportunities in the classroom. With the BLPP assessment, I sought to remove or otherwise address the structural impediments in the way of scholarly research that vulnerable students routinely confront (see, for example, Pascarella et al. and Walkington).

I introduced students to BLPP during the fourth week of the semester after they had read short texts by myriad canonical and lesser-known British and Anglophone authors such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Dickens, Toru Dutt, and Olive Schreiner. This approach familiarized my students with the wide range of authors, or what I call “British literary profiles,” whose voices collectively constitute the landscape of British literature surveyed in our course. Students completed their essays during the eighth week of the semester, making BLPP the midterm assessment for the course.

For BLPP, I asked my students to research and discover global Anglophone authors who are either not part of the Victorian canon or, despite being well-known, can be studied with a renewed thematic/cultural focus. In this way, the assessment enabled students to select their preferred method of contributing to our classroom either by rediscovering or by reexamining an author of their choice. BLPP aligns with the pedagogical philosophy that informed how I selected texts for my “British Literature II” syllabus. By having students read excerpts rather than complete texts, I gave them the cognitive space and time necessary for equitable study of British and Anglophone global authors beyond the established literary canon. Works by diverse authors are equally represented in my syllabus instead of accommodated in small amounts around canonical authors and their longer works. BLPP extends this representative rather than accommodative approach by enabling students to recover overlooked authors or reevaluate well-known authors based on their individual interests.

The twenty-first century has seen myriad efforts in recovering forgotten achievers in fields such as literature, art, science, entrepreneurship, and activism. These efforts include restoring the achievers to their rightful place in public memory and academic curricula by running obituary series such as Overlooked in The New York Times, digital humanities recovery projects such as One More Voice, and events such as the recent Bearing Untold Stories hybrid interdisciplinary symposium. Just as One More Voice’s mission statement asserts that “there is always one more voice to recover from the archives” (emphasis original), I contend that there is always one more author to learn about in a literature course, and students play an important role in the process.

I previously engaged my students at Prairie View A&M University in recovery work with “Forgotten No More,” an assessment I developed for an introductory humanities course focused on nineteenth-century women’s rights, which asked students to discover and write about obscure global women achievers (see Das). While recovering obscure nineteenth-century women achievers might be expected in a course centered on gender, BLPP extended recovery work to a course typically focused on the canon.

Thus, BLPP enabled students to transgress the canonical boundaries of British literature with their discoveries. Students accomplished this by deploying a combination of three skills. First, students searched online for specific information based on their broad interests, which is a skill at which most were adept. Second, they honed the skill of filtering online search results by identifying credible sources. Third, they acquired the skill of critical evaluation and selection by reviewing topics and choosing a specific subject (in the case of BLPP, a British/Anglophone author) on which to write.

As a result, the assessment was not only representative of the diversity of the British literary field, but also of the academic interests of the student population in my classroom. For example, one student was invested in resurrecting forgotten women achievers and utilized BLPP to write about nineteenth-century Australian novelist Matilda Jane Evans, who has become obscure despite her prolific literary output. Another student channeled their interest in the complex history of abolitionism to write about eighteenth-century Nigerian abolitionist Olaudah Equiano. A third student explored their passion for contemporary poetry and oral poetic performance by writing about contemporary British poet Malika Booker.

I graded my students’ BLPP essays irrespective of whether they chose to research a new author or revisit a canonical one. A student who decided to rediscover an obscure author wrote a successful essay if they satisfactorily justified their choice and critically analyzed the impact of the author’s life and work. Similarly, a student who elected to reexamine a well-known author wrote a successful essay if they satisfactorily justified their reexamination and critically analyzed an overlooked aspect of the author’s life and work.

My students’ responses to the intellectual liberty BLPP afforded them was overwhelmingly positive for two primary reasons. First, several students expressed relief that at a time in the semester rife with midterm assignments, BLPP did not cause them additional stress and anxiety. They had already been working on their essays for several weeks instead of having to prepare for a timed examination. Second, students appreciated the import of their own intervention. Based on responses I received, including a student who professed a newfound appreciation for British literature, students valued the agency to select an author.

Moreover, by having the option to investigate British literary profiles beyond the literary canon or to contemplate popular authors in a new light, students were able to grasp and exercise the multifaceted power of scholarly research. The assessment effectively conveyed to my students that, based on their individual academic interests, they had the capacity and liberty either to venture into uncharted territory and revive obscure knowledge or to dig deeper into a widely-explored landscape to reveal overlooked knowledge.

And for my students of color, the choice to follow their interests is particularly important since it loosens the rigid expectations that academia has for scholars of color to conduct race- and/or area-focused research. As someone who teaches in a minority-serving American institution, I would find it counterintuitive to demand that my minority students focus solely on resurrecting minority authors, while simultaneously advocating for resisting the same racial boundaries that define canonicity in British literature. Thus, for BLPP, one of my students with a keen interest in the history of British speculative fiction reexamined J. R. R. Tolkien and the enduring influence of his works. Another student explored their interest in British children’s literature by writing about the early life of Anna Laetitia Barbauld. These contributions, along with those by students who resurrected obscure authors, upheld the representative philosophy of our classroom and the course, which consists of Anglophone literature of and beyond the established canon.

My approach, in turn, speaks to a critical debate about area studies that has been ongoing since at least the late twentieth century, when U.S.-based scholars warned against the exploitative potential of area studies, as it “develop[s] a body of elite scholars capable of producing knowledge about other nations to the benefit of ‘our’ nation” (Rafael 93). Comparing twentieth-century area studies in the U.S. to nineteenth-century classical studies in Britain, Rafael argued that the former “shatter[ed] the intellectual isolationism of Americans” in the same way that the latter “resulted in a break with ‘British provincialism,’ leading to the acquisition of a far-flung empire” (93). In contrast with the U.S.-based elite area studies scholarship Rafael described, Premesh Lalu recently pointed out the methodological limitations encountered by area studies scholars outside the U.S.: “in the United States, […] scholars today transgress disciplinary boundaries readily and freely, experiment endlessly, and shift directions effortlessly, while their African counterparts are pressured by demands for more case studies” (Lalu 129).

Substantiating Lalu’s statement, U.S.-based scholars recently called for the transgression of disciplinary boundaries: “[I]t might be time to collaborate with disciplinary formations such as area studies, which are marked by their cross-disciplinary and primarily non-European focus. To bridge the gap between nineteenth-century studies and area studies – to twin, in other words, the temporal axis with a spatial one – is one way to ‘lateralize’ Victorian Britain, to think of widening in coeval terms” (Banerjee, Fong, and Michie 6-7). Recalling Rafael and Lalu’s critique about the racial/ethnic/national stereotyping of scholars of area studies while heeding the call to transcend disciplinary boundaries in the U.S., I argue that teacher-scholars of British literature must carefully consider whom they expect to answer this call. In practice, I employ this care with assessments such as BLPP in order to inform BIPOC students of the wide range of British literature without bestowing on them the burden of dismantling the canon in one specific way.

In the future, when pandemic-related challenges and inequities hopefully subside, I envision transforming BLPP into an interactive presentation project, thus widening the dissemination of students’ rediscoveries and reexaminations in the classroom. I also plan to integrate multimodal writing into the assessment, with blogs or student-led digital humanities projects that can enhance BLPP. Students are much more conversant in digital technologies in the twenty-first century compared to earlier decades. A digital approach would give them the opportunity to capitalize on their digital literacy and is in the spirit of the assessment in terms of prioritizing student initiative. Notably, BLPP demystified the process of research and showed my students that rigorous scholarship truly begins with them in the undergraduate classroom. BLPP enabled my students to realize that with the power to seek and disseminate the knowledge they deem interesting, they can boldly intervene in an eclectic academic field.

Works Cited

Banerjee, Sukanya, et al. “Introduction: Widening the Nineteenth Century.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 49, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1–26.

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 10 July 2020.

Das, Riya. “Transgressing with Rediscovery: The ‘Forgotten No More’ Essay.” Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, Spring 2021.

Lalu, Premesh. “Breaking the Mold of Disciplinary Area Studies.” Africa Today, vol. 63, no. 2, 2016, pp. 126–31.

Pascarella, Ernest T., et al. “First-Generation College Students: Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes.” The Journal of Higher Education, vol. 75, no. 3, 2004, pp. 249–84.

Rafael, Vicente L. “The Cultures of Area Studies in the United States.” Social Text, vol. 41, 1994, pp. 91–111.

Walkington, Lori. “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education.” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, vol. 39, 2017, pp. 51–65.

Developer Biography

Riya Das is Assistant Professor of English (British/World literature) at Prairie View A&M University. She is currently working on her first monograph, Women at Odds: Indifference, Antagonism, and Progress in Late Victorian Literature, with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, Victorian Literature and Culture, and other venues.

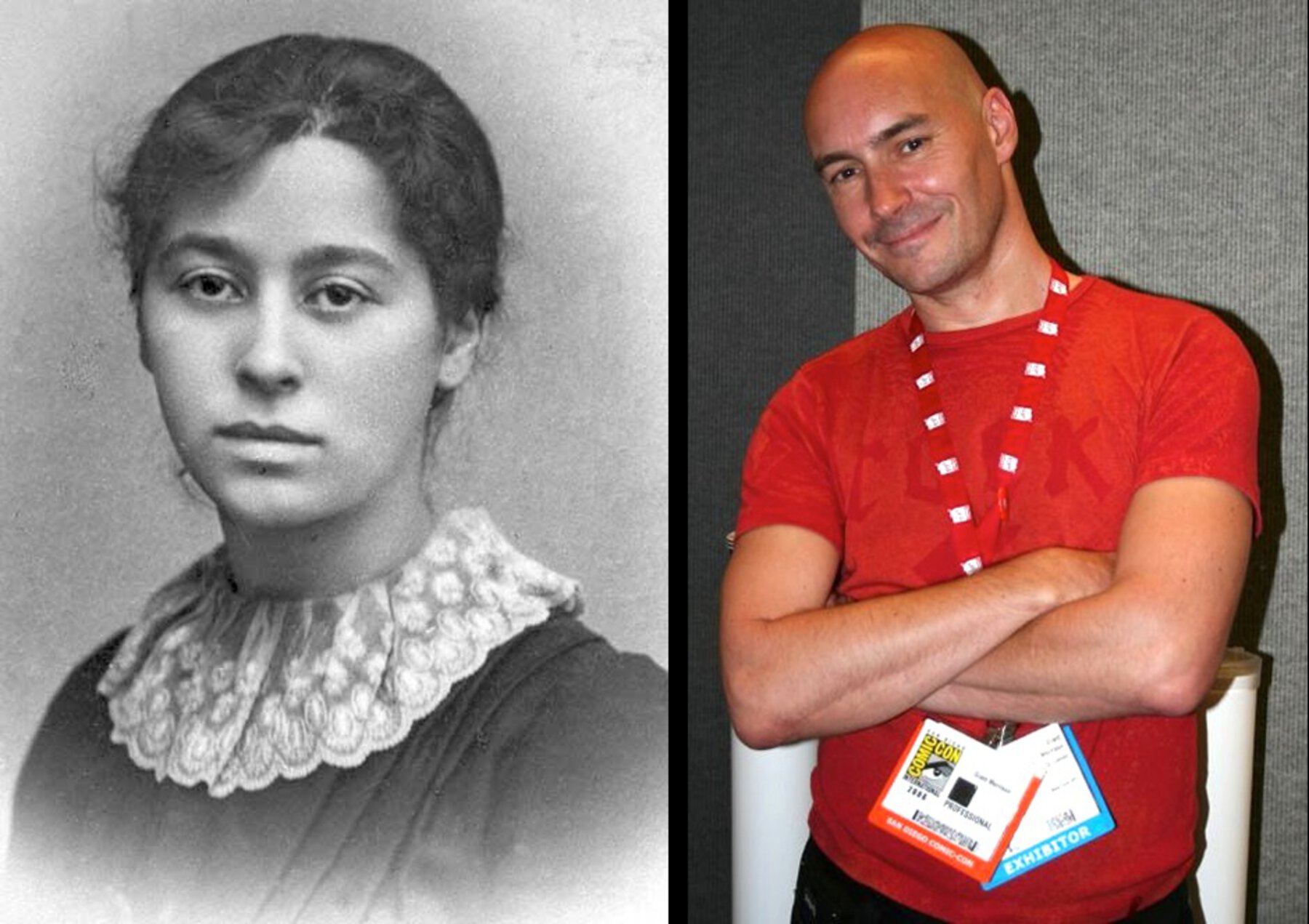

Tile/Header Image Captions

(Left) Anonymous. Amy Levy. [nineteenth century]. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

(Right) PDH. Grant Morrison. 22 July 2006. Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

Page/Assessment Citation (MLA)

Riya Das, dev. “Recovering and Reevaluating Anglophone Writers.” Sarah Ohmer, peer rev.; Adrian S. Wisnicki, assess. guide; H Fogarty, copyed. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2023, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/assessments/recovering_reevaluating.html.