Rhetorics of Empire

Assignment Production Details

Developer: Gregory Brennen Contact

Peer Reviewer: Jacqueline Barrios

Assignment Guide: Sophia Hsu Contact, Jude Fogarty Contact

Webpage Developer: Adrian S. Wisnicki

Associated Assignment: Taylor Soja, “Victorian Histories for Today”; Ashley Nadeau, “Audio Encounters with Victorian Poetry”

Cluster Title: Beyond the Essay

Publication Date: 2025

Assignment Overview

Download the peer-reviewed assignment: PDF | Word

I developed this assignment in Spring 2022 when I was a Marion L. Brittain Fellow in the Writing and Communications Program at Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Georgia Tech embraces a multimodal approach to teaching composition and communication. Multimodality is an approach to composition rooted in the New London Group’s 1996 call to expand pedagogy beyond the “textual” to additional “modes of meaning-making” such as “the visual, the audio, the spatial, [and] the behavioral” (Cazden et al. 64). Georgia Tech uses a distinctive “WOVEN” approach to multimodal composition, teaching written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal communication (Holdsworth et al.; “WOVEN Communication”). WOVEN is both an acronym and a metaphor for how different types of communication interact and reinforce one another.

I entered the Brittain Fellowship somewhat apprehensive about designing and teaching multimodal assignments: I don’t think of myself as especially technologically savvy, and my previous experience teaching composition had been in relatively traditional programs that focused on the essay. After many years as an undergraduate, graduate student, writing tutor, and instructor, I had become rather disciplined: academic essays were what I was most comfortable writing, assigning, and evaluating. Yet I soon came to find multimodality invigorating. Georgia Tech’s multimodal vision invited me to reassess my own reliance on the essay as the coin of the realm in humanities classes.

The academic essay is, after all, a specific disciplinary genre that cannot by itself accommodate the varied and constantly changing ways that students communicate and will communicate in the future. Multimodality, I’ve come to believe, can both challenge and thus “undiscipline” the inequitable constraints of traditional academic genres and serve a practical purpose (Chatterjee, Christoff, Wong; Sharpe 13). It empowers students to draw on their own languages, dialects, and modes of communication and helps students become versatile communicators prepared to adapt their communication abilities for a range of personal, academic, and professional rhetorical situations.

This assignment was the third of three major “artifacts” in my Composition II class on the theme of “Narratives of Empire: Rhetorics & Media of Victorian Imperialism.” The second in a two-course, first-year writing sequence, Composition II asks students to cultivate rhetorical awareness, practice multimodal communication, and engage in an extensive research project (“English 1101 and 1102”). Instructors have the freedom to develop their own topics and choose their own primary texts. My version considered Victorian imperialism as a rhetorical, narrative, and media phenomenon and sought to analyze the rhetorics of empire via research and primary source analysis, including both literary texts and Victorian “new media” such as photography.

In this particular assignment, students practiced multimodal communication by integrating written, oral, verbal, electronic, and nonverbal communication to effectively lead a class session. This assignment was designed to be a pedagogical experiment, meeting the course’s goals of research and multimodal communication while piloting an alternative to a traditional research paper or presentation. Working in teams, students designed and executed research projects that culminated in interactive, class-length presentations. Groups researched flashpoints in the history of Victorian imperialism and educated their peers about their historical, cultural, and rhetorical contexts.

This project seeks specifically to undiscipline the hierarchical power structure of the classroom and the established genre of the research paper as means of assessment by supplementing or even replacing it with a more inclusive, flexible, interactive, and student-centered project. First, this assignment intentionally decenters the instructor, leveling out the hierarchical model that is the default of the traditional classroom and giving students ownership of and responsibility for not only their own learning experience but also that of their peers. Students, therefore, used their research, collaboration, and communication abilities to become teachers. The opportunity for students to become teachers has the potential to empower students and help them both to become and to see themselves as experts; it also allows them to practice a highly transferrable skill.

Second, this assignment explicitly does not privilege writing in standard academic English but instead values a variety of communication skills. Traditional assignments in academic writing classrooms can be exclusionary because, as writing studies scholars such as Asao B. Inoue have influentially argued, “most if not all writing courses… promote or value first a local SEAE [Standardized Edited American English] and a dominant white discourse” (14).

One of the promises of multimodality is to enable students to practice whatever combination of discourses and modes of communication will allow them to say what they want and for effective and versatile communication to be valued over adherence to “dominant language rules” (Young 111). In doing so, this assignment embraces what Vershawn Ashanti Young calls “code meshing” by enabling students to simultaneously practice multiple “dialects, international languages, local idioms, chat-room lingo, and the rhetorical styles of various ethnic and cultural groups” and by valuing such diverse communication (114).

This flexibility allows students of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds and learning styles to thrive as they communicate, research, and think critically about the rhetorics of Victorian imperialism. I found such flexibility particularly fruitful for the population of students at Georgia Tech. Demographically, Georgia Tech’s student body is relatively diverse; white (35%) and Asian (34%) students are the largest groups, with smaller cohorts of Black (8%), Hispanic (8%), and international (9%) students (“Student Demographics”). Students are mostly traditional-aged and high-achieving; Georgia Tech is highly selective, admitting 36% of Georgia applicants and only 12% of applicants from other states or abroad in its most recent cycle (“Georgia Tech Admission”).

As an instructor, what stood out to me the most about the student body was its disciplinary makeup. As one would expect from a technology institute, the overwhelming majority of students study science and technology (STEM) fields; a full 86% of the entering students in 2021, the year I started at Georgia Tech, were pursuing STEM majors (“Freshman Cohort: Fall 2021”). In general, these students tended not to gravitate towards the humanities, and while my classes certainly also emphasized written communication and essay-writing, the opportunity for a multimodal project allowed students who might excel more in other forms of communication, such as electronic or visual, to flourish.

However, the added demands of collaboration, balancing multimodal communication, and the not insubstantial risk of the instructor giving up “control” of numerous class sessions (six full classes for me) require intentional and careful scaffolding, or breaking assignments down into smaller steps that build on each other. In this case, incremental assignments and activities building up to the main event included a group constitution, an annotated bibliography, a lesson plan, and peer review. Scaffolding is important not just to the steps of the assignment itself; the skills, interpersonal dynamics, and community need to be deliberately honed from the beginning of the semester for such a large-scale, relatively high-stakes collaborative learning project to succeed. Practicing smaller-scale, lower-stakes presentations and team-based learning tasks throughout the semester helps to build the skills and confidence for such a major project.

Students often find large-scale group projects intimidating, annoying, or anxiety-inducing. These reservations come from a variety of sources depending on students’ positionalities and experiences. Sometimes high-achieving students feel like they’ve had to “carry the team” in past projects; sometimes students worry they won’t be able to contribute as effectively for any number of academic or material reasons; sometimes students think having to coordinate with others is an extra thing to worry about in a busy schedule.

Regardless of the source of students’ hesitation, explicitly discussing the pitfalls and possibilities of collaboration helps to generate buy-in and mitigate students’ reservations. In this class, we began the project by reading a chapter from WOVENText on collaborating effectively in multimodal, team-based projects (Holdsworth et al., ch. 7). Students then collaboratively produced a group constitution in which they addressed such questions as how they would communicate, what skills each person would bring to the table, how they would use their meeting time, and what they would do if someone’s contributions did not meet expectations.

Incorporated into the rubric for this assignment was 20% set aside for groupmates to evaluate each other’s performance. This provided some accountability without the professor being too involved in internal group dynamics; the constitution asked groups to reflect and agree on the criteria by which they would evaluate each other. In addition to the peer evaluations, a further 20% of the final grade was in the hands of the audience, the fellow students each group was teaching. Brief, anonymous surveys were completed at the end of each lesson in which each audience member rated the effectiveness of the lesson.

Thus, this assignment actualizes the leveled classroom philosophy by handing a significant amount of the grade (40%) over to students. This assignment is really about the instructor creating conditions for students to flourish and then – except for providing advice and support – largely getting out of the way. Because I was teaching four sections of Composition II in the semester I piloted this assignment, I’ve seen twenty-four of these lessons, equivalent to around eighteen hours of class time. All twenty-four groups executed class sessions that were excellent and engaging enough to validate the assignment design and inspire me to adapt and disseminate it.

One particularly memorable example was by Andrew Hsu, Lara Bailen, Matthew Kerner, and Srujal Gawali, whose lesson on the Morant Bay Rebellion stood out for its excellent collaboration, remarkable audience awareness and engagement, and effective multimodal communication.1 This group executed a complex, perfectly-timed class period rich with interactive activities that displayed a considerable array of communication skills. While the core of the presentation was a twenty-five slide deck, it never felt like a lecture. I was particularly impressed by the students’ integration of close reading exercises and array of interactive activities, including collaborative annotation, that thoroughly demonstrated that they had indeed become reading and writing teachers in their own rights.

Most significantly, Andrew, Lara, Matthew, and Srujal’s lesson demonstrates how effective use of multimodal pedagogy can disrupt the norms of traditional genres. The slide presentation format can, depending on how it is deployed, reproduce many of the classroom norms that this assignment aims to disrupt, such as privileging SEAE, enforcing linear thinking and argumentation, requiring the audience to be oriented towards a screen, and relegating control of the space to the person presenting.

By contrast, the slides in this lesson served as launching pads for the audience: far from passively observing a presentation, they were encouraged to participate in or even take ownership of their own learning experience. Andrew, Lara, Matt, and Srujal each presented portions of the slideshow and led segments of the discussion; they used their slides to create a network of other media, ranging from Google Slides and Docs to present content to a Kahoot! game and QR code to engage the audience; and they utilized the physical space of the classroom by having students leave their seats to sort cards representing different participants in the Morant Bay Rebellion and tape them to different areas of the classroom walls.

For me as a teacher, a benefit of this assignment was the opportunity to teach students how to teach and to reflect on my own pedagogical practices. I explicitly framed this assignment as an opportunity to practice teaching, a highly transferable skill. While perhaps only a handful of my students will become professional teachers, each of them may need to leverage their multimodal communications skills to educate colleagues, customers, managers, peers, or investors. In general, most of the students in my first-year writing classes were majors in computer science or some form of engineering and pursuing related careers, such as working in the technology industry.

The process of helping students develop their lessons forced me to reflect on and articulate my teaching practices. Students asked excellent, probing questions that got at the fundamentals of teaching: How do you get people to say things when you ask a question? How do you get people to do what you want them to do in an activity? How do you know how long something will take? What do you do if an activity takes more or less time than you expected? Like all teachers, I’ve developed ways of handling these situations, but I don’t often think explicitly about my own strategies, let alone articulate them to curious students.

Building in time and creating space for such conversations to happen is critical. In Spring 2022, I was able to dedicate a full month to this assignment; I even replaced two normal classes with group meetings to meet with each group one at a time. Leveling the classroom by inviting students to take on the instructor’s role is a powerful goal, but it requires intensive support from the instructor and the whole classroom community.

The biggest restriction on this type of assignment, at the scale that I initially designed it, is that it requires a degree of curricular flexibility that, at least in my career, I’ve found somewhat extraordinary. In the Georgia Tech curriculum, I had the freedom – indeed, almost a mandate – to make a major assignment a multimodal group project and to dedicate weeks of class to it. That freedom certainly doesn’t exist everywhere, particularly in composition programs, many of which require a specific sequence of essays. For just that reason, I haven’t yet had the opportunity to teach this assignment again given the curricular restraints of my current institution.

Despite this, I have begun exploring ways to integrate lower-stakes, smaller-scale team-based multimodal work into my classes. For example, in a Spring 2024 class, groups of students led shorter discussions on scheduled days spread out throughout the semester. On a larger level, I advocate for those educators with the privilege and opportunity to do so to work towards including more multimodal and/or team-based assignments in their classes and curricula, whether at the level of an individual syllabus, an academic program, or the whole general education curriculum.

My colleagues at the University of Tampa, for example, recently took the opportunity of a new liberal-arts based general education curriculum focused on the local and global experiences to make a multimodal project a major assignment in humanities core courses. For the core class that I developed there – a multi-section course taught by other instructors as well – the multimodal project is team-based and employs many of the structures and philosophies from the assignment I share here.

In today’s academy many of us trained as Victorianists rarely teach courses in Victorian literature. Whatever Victorian content we teach has to find a place in the general education classroom, often in composition courses. There are, of course, plenty of reasons to lament the state of academic hiring and the limited ability of many departments to staff and fill courses in Victorian – or any – literature, but it is also worth thinking about how we can use our training, contribute to the field, and even bring the study of Victorian culture to a wider audience by designing creative assignments for the composition classroom. I don’t think this assignment is useful only in composition classes, but part of my goal here is to share a model of how the study of Victorian imperialism can flourish in them.

Looking back at this assignment with a couple years’ critical distance, it strikes me that the “flashpoints” of imperialism I offered students were wars and/or rebellions. There is certainly no need for all the projects to be focused on armed conflict. That just happens to be how I did it in 2022 in part because I used my own lessons on the Crimean War to model this kind of presentation for students. Any event that caused ripple effects in Victorian media and culture and that has had a post-Victorian cultural legacy could be just as effective. To keep things manageable for the teams, it is important for the events to be of limited scope with somewhat stable start and end dates: for instance, the Great Stink of 1858 would work better than the Industrial Revolution. When I teach this assignment again, I’ll broaden out the possible topics.

Giving students the space to research and identify their own topics, rather than choosing from a menu of options pre-selected by the instructor, would also better express the democratizing philosophy underlying this assignment. I didn’t do that in this case mainly because this was a course in multimodal communication first and Victorian imperialism second; you can only ask students to do so much reading and research when they’re also trying to master new communication skills. In a class with the scope for guiding students in more self-directed research, inviting students to choose their own topics could be an improvement on the assignment as I’ve presented it here.

In the future, I would also like to set aside class time after the presentations for everyone to reflect on the different lessons holistically. I can imagine a variety of formats for doing this: writing exercises, a roundtable discussion featuring representatives from each group, or a simple large-group discussion. Students did write reflectively about the project on an individual basis, but because of time constraints, we could not engage in class-wide reflection and synthesis. I would like to do so in the future and suggest that as a possible enhancement to this assignment.

Group work can reinforce inequitable hierarchies among students, and in keeping with the rhetorical grounding of this assignment, it’s important to consider the circumstances of the student population and institutional context when adapting this assignment. While inequities among students take various forms, I’d like to close by thinking about some of the potential material inequities that can be particularly fraught for team-based assignments that rely on the use of technology. I acknowledge that Georgia Tech’s institutional privilege and the nature of its student body sheltered my students and me from some of the challenges this assignment might raise in other institutional contexts.

While Georgia Tech students certainly come from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and personal circumstances, all my students were traditional-aged (18-23, mostly closer to 18), full-time college students. A full 97% of first-years at Georgia Tech live on campus (“Are First-Year Students”), and all students are required to own a laptop (“Required Computer Ownership”). While I don’t want to paper over the differences in my students’ individual circumstances and resources, these institutional realities nevertheless ameliorated concerns about access to computers and high-speed internet and availability to meet on campus that would be major factors in many educational contexts.

In adapting this assignment for pedagogical situations with greater proportions of non-traditional students or where students’ access to computers and the internet is not guaranteed, it would be necessary to revise the assignment to take these circumstances into account. For example, best practices for asynchronous group collaboration could be explicitly included in the instruction so that students with limited availability to meet on campus or limited access to technology would not be disadvantaged. As well, in cases where this assignment is used in synchronous, in-person classes, setting aside class time for groups to meet and collaborate can facilitate access.

While this assignment is designed to be maximally flexible and inclusive, it will have limitations and the potential to reproduce inequities in different contexts. In the spirit of rhetorical awareness, this assignment should be adjusted for each situation and audience. Embracing the full range of the affordances of multimodality will, I hope, enable this assignment to transfer to a variety of pedagogical situations.

I’d like to thank Anna Gibson, the participants, and the audience members in the “Just Assignments: Rethinking Student Work in the Victorian Studies Classroom” panel at the 2022 North American Studies Association Conference for the opportunity to share, discuss, and continue thinking about this assignment. Thank you as well to Jude Fogarty, Sophia Hsu, Ashley Nadeau, Taylor Soja, and Jacqueline Barrios for valuable feedback on this assignment and essay. Finally, I gratefully acknowledge my students at Georgia Tech, especially those cited above, for making this assignment a success in the classroom.

- Thank you to Andrew, Lara, Srujal, and Matthew for their permission to reference their work and credit them by name. Back to text

Works Cited

“Are First-Year Students Required to Live on Campus?” Georgia Institute of Technology, 2022.

Cazden, Courtney, et al. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 66, no. 1, 1996, pp. 60–92.

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Los Angeles Review of Books, July 2020.

“English 1101 and 1102: Composition I and II.” Georgia Institute of Technology, 2024.

“Freshman Cohort: Fall 2021” (PDF). Georgia Institute of Technology, 2024.

“Georgia Tech Admission Announces Decisions.” Georgia Institute of Technology, 27 Mar. 2023.

Holdsworth, Liz, et al. WOVENText. Georgia Institute of Technology, 2023.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. The WAC Clearinghouse, 2015.

“Required Computer Ownership.” Georgia Institute of Technology, 2023-2024.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.

“Student Demographics.” Georgia Institute of Technology, 2024.

“WOVEN Communication.” Georgia Institute of Technology, 2024.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. “Should Writer’s Use They Own English?” Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2010, pp. 110–17.

Beyond the Essay Series

This cluster challenges instructors to think beyond the traditional essay often used in Victorian studies classrooms by providing examples of multimodal and/or public-facing assignments. Through creative assignment design, this cluster demonstrates that students can participate in the undisciplining of the field via projects that encourage critical and multimodal remaking, engagement, and communication, as well as those that reimagine and expand the audience of Victorian studies.

Developer Biography

Gregory Brennen is Teaching Assistant Professor of English and Assistant Director of First-Year Composition at Oklahoma State University (OSU). Prior to joining OSU in 2024, he taught writing and literature at the University of Tampa, Georgia Tech, Duke, Elon, and the Leadership Enterprise for a Diverse America. This project originated with his work as a Marion L. Brittain Fellow in the Writing and Communication Program at Georgia Tech in 2021-22. He holds a Ph.D. in English from Duke University with a dissertation titled “The Serial Imagination: Novel Form, Serial Format, and Victorian Reading Publics.” His research and teaching interests include Victorian literature, serial media, the British empire, multimodal composition, and academic writing.

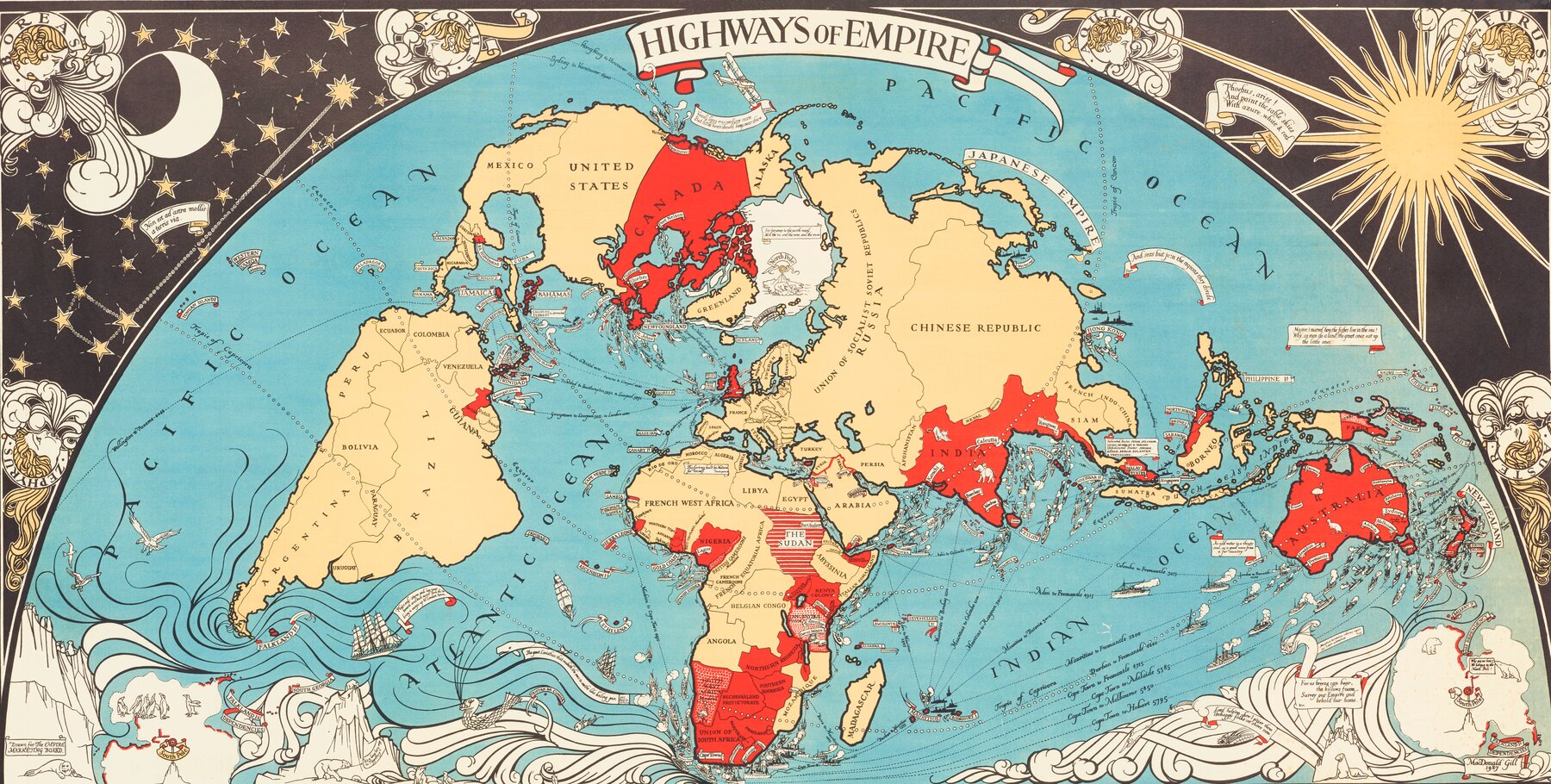

Tile/Header Image Caption

Gill, MacDonald. “Highways of Empire.” 1927. GH021711, Museum of New Zealand | Te Papa Tongarewa. No Known Copyright Restrictions.Page/Assignment Citation (MLA)

Gregory Brennen, dev. “Rhetorics of Empire.” Jacqueline Barrios, peer rev.; Sophia Hsu, Jude Fogarty, assess. guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2025, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/assignments/team-based_learning.html.