Audio Encounters with Victorian Poetry

Assignment Production Details

Developer: Ashley Nadeau Contact

Peer Reviewer: Jacqueline Barrios

Assignment Guide: Sophia Hsu Contact, Jude Fogarty Contact

Webpage Developer: Adrian S. Wisnicki

Associated Assignment: Taylor Soja, “Victorian Histories for Today”; Gregory Brennen, “Rhetorics of Empire”

Cluster Title: Beyond the Essay

Publication Date: 2025

Assignment Overview

Download the peer-reviewed assignment: PDF | Word

I developed the assignment, “Narrating Victorian Poetry” – which tasks students with studying and recording a recitation of a Victorian poem and reflecting on their process – as a supplement to an ongoing research project I am conducting that studies the role of audiobooks in the undergraduate literature classroom. This research project, which I developed beginning in 2020, was the direct result of trying to address the specific needs of my students.

I teach at Utah Valley University (UVU), a former community college that is now a regional university with the largest number of enrolled students – well over 40,000 – in the state. As an institution, UVU serves a dual mission as an open-enrollment community college and teaching university, and it caters to a student population shaped both by its open-access, vocational ethos and by the dominant religion of Utah, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

As of 2022, 38% of UVU students are first-generation, 37% are married or in a domestic partnership, 14% support at least one child, 82% are employed, and 28% work more than 31 hours per week. What these figures mean for the classroom is that the vast majority of my students are juggling the competing demands of family, work, and school, and it is not all that uncommon for students to show up to class in their work uniform or with a sleeping infant in tow. As such, accessibility is highly valued at UVU. Making a course accessible means not only addressing the needs of students with disabilities but also being cognizant of the cost of course materials for a student population that is by-and-large loan adverse and pays their tuition out of pocket. It likewise means being flexible with the many non-traditional students whose busy lives require a heroic level of multi-tasking.

These demographic conditions are why I should not have been surprised when I discovered in 2019 that two of my students were resorting to audiobooks to manage the “loose baggy monster” that is a Victorian literature survey reading list. One student was the primary caregiver of a young child; the other had a full-time job. Both wanted to do well in the class. Inspired by their efforts to stay caught up with the reading by any means necessary (and to be honest, my own enjoyment of the medium), I set out to find out how many of my UVU students occasionally listen to an assigned text in their English classes (over half!) and whether audiobooks could serve as legitimate supplements to my British literature surveys and Victorian literature courses and a means of promoting accessibility.

A study I conducted in Fall 2023 comparing listening and reading comprehension in a Victorian literature survey course found no significant difference in performance between visual media and audiobook readers, which should allay the concerns of those who question the status of audio reading as reading (Nadeau and Craig). This result is in keeping with two recent meta-analyses that found that reading and listening comprehension outcomes are variable across studies and that there is no clear indication whether these two mediums are significantly different in terms of understanding (Clinton-Lisell; Singh and Alexander). Recent fMRI studies in cognitive science have also found no difference in the semantic processing of written and audio text, suggesting that these modes of narrative immersion may be less far apart than many literary scholars and educators assume (Deniz et al.).

While audiobooks may not provide an advantage (or disadvantage, for that matter) for neurotypical readers, student accounts indicate that they provide a much-needed accommodation for non-traditional and neurodiverse students. This accords with research in K-12 education and literacy, which finds that audiobooks facilitate content acquisition and can be valuable assistive devices for students with learning disabilities like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Boyle et al.).

Framing audiobooks as assistive devices rather than as shortcuts for the lazy recuperates their historical relationship with readers with disabilities as recorded books for the blind (Rubery, “Talking Books”). It also highlights their utility for making prohibitively “heavy” courses, like surveys of British literary history and Victorian literature, accessible for chronically overburdened students. Given UVU’s demographics and the fact that students with learning disabilities attend community colleges at a higher rate than other higher education institutions (McCleary-Jones), it seems only wise to embrace audiobooks as supplementary teaching material.

None of this is to say that I think listening to and reading Victorian literature are exactly the same. But perceived differences in the reading experience don’t rule out the possibility that audiobooks offer other literary interpretive possibilities and modes of engagement. Many of my students report discovering just how funny Charles Dickens or Jane Austen can be while listening, something they may never have discovered while trying to silently parse the unfamiliar language and forbidding sentence structure of nineteenth-century texts. They felt for the first time how exciting, propulsive, and wry nineteenth-century literature often is. For affect studies scholars and scholars of the empathetic dimensions of reading (see, for example, Keen), the strong emotional and kinesthetic responses elicited by audiobooks are noteworthy.

Of course, we need not turn to other fields to justify the inclusion of audiobooks in the Victorian literature classroom. As Ivan Kreilkamp, Kate Nesbit, and Matthew Rubery, amongst others, point out, reading aloud was a significant part of Victorian social life and it was practiced in both private domestic spaces and public sites of assembly and entertainment. In listening to audiobooks, today’s students are experiencing old ways of reading with new technology. Still, there are real limitations to teaching with audiobooks, not the least of which is cost and the dominance of the Amazon subsidiary, Audible, over the audiobooks marketplace. Demand drives production in this increasingly competitive corner of the publishing industry, which means that while there are dozens of audio editions of Jane Eyre, there are just three of The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands.

At the present moment, availability and diversity are somewhat at odds, forcing teachers who embrace audiobooks to choose between readily available, high-quality audio editions and expanding their curriculum to include authors from underrepresented groups or genres of writing besides the novel (James F. English further addresses this dilemma). In other words, I was finding it difficult to move beyond the “whiteness (as white supremacy)” of the Victorian literary canon and “undiscipline” my classroom at the same time I was trying to accommodate my non-traditional and neurodiverse students with audiobooks (Chatterjee et al. 370).

This brings me to my “Narrating Victorian Poetry” assignment, which I designed in Fall 2022 as an optional alternative to a traditional short essay assignment in an upper-division, Victorian literature survey course. Inspired in part by my students’ desire to read more poetry alongside our selection of audiobook novels and short fiction, and by Catherine Robson’s study of recitation as a pedagogical norm of the past, I developed an assignment that would connect my course’s orientation towards aurality with my efforts to expand the body of Victorian writers represented on my syllabus beyond those whose works are readily available as recorded readings.

Like Victorian fiction, nineteenth-century poetry and verse were often experienced socially and aurally (Behlman and Moy; Cohen). Less the coherent literary category we think of today, nineteenth-century poetry was more a “hodgepodge of genres, formats, and media that engaged readers in many different ways” (Cohen 22). For example, in recounting the popularity of nineteenth-century American balladmongers, Michael C. Cohen observes that their peddled poems were performed to gathered family rather than read silently in private (20).

Likewise, Lee Behlman and Olivia Loksing Moy point to the variety of audiences who encountered Victorian poetry and the many different spaces of consumption for reading and “‘nonreading’—that is, memorizing, reciting, imitating, and even mocking” Victorian verse (Behlman and Moy 8). Combining Behlman and Moy’s capacious framing of “nonreading” with my own critical stance towards the traditional assumption that listening to an audiobook is not reading, my assignment plays with conventional approaches to teaching Victorian poetry and moves beyond the discipline-standard literary analysis essay.

The resulting project tasks students with creating their own audio narration and interpretation of a text by instructing them to select, study, and post a recorded recitation of a Victorian poem of their choice in our class’s shared anthology on the Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education (COVE). For the first iteration of the assignment, I required my Fall 2022 students to write a brief narrator’s statement (2-3 pages) accompanying their recording and reflecting on their process and interpretation as expressed in their voicing of the poem.

To prepare for this assignment, we first read Alfred Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and then listened to his 1890 phonographic recording of the poem. We then discussed the choices Tennyson made as a reader of his own work and how his reading compared to how they imagined the poem should sound. Following this, we practiced an in-class collaborative recitation of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “The Cry of the Children” and discussed as a group how the poem’s sonic dimensions contribute to its effectiveness as political commentary. This limited scaffolding was instructive regarding the need for clear directions and additional guidance on unconventional assignments. As I discovered, my students also needed instruction on how to convert voice memos on their phone and upload them as audio file annotations on our shared COVE Studio anthology.

Given free rein over their choice of poem for recitation, it is perhaps unsurprising that most students reached for anthology standards. Nevertheless, their narrator’s statements revealed deeply personal and thoughtful encounters with the texts. Emily Brontë’s “No Coward Soul is Mine” was especially popular that semester, with several students reflecting that existing recordings on YouTube were too somber. Connecting Brontë’s meditation on faith with their own attitudes towards religion, these students reported trying to imbue their recitations with enthusiasm. As one explained, “I wanted to convey a dynamic character [...] While I see the value of [a solemn tone] in expressing a deep reverence for the narrator’s beliefs, I want my performance to challenge the typical notion of reverence for God.” Other similar responses underscored “a sense of hope” and a desire to “recite the poem in a passionate and brave way.”

Other students reflected on the politics of representation and framed their recitations in terms of what it felt like to give voice to the views of the past from the perspective of the present. Writing about her experience of reciting Browning’s “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,” one student explained:

In reciting the poem, I was mindful of the fact that I am a white woman reciting the struggle of a slave. Of course, Elizabeth Barrett Browning was herself a white woman reciting the struggles of a slave. Because of this fact, it was extremely important to me that I be as respectful as possible, while being aware of the differences between my experiences and the experiences of a black slave. This project impacted my appreciation and understanding of the context of the annual the poem was published in and learning Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s background made me realize how it is both problematic and important.

For this student, the self-awareness promoted by reciting Browning’s words in her own voice resulted in a productive engagement with issues of racial representation and privilege as she struggled to imagine the experience of the poem’s speaker, a self-emancipated enslaved woman who commits infanticide. Although this student’s decision to recite Browning’s dramatic monologue risks re-enacting the minstrelsy that Melissa Gregory argues is embedded in this genre (and this poem specifically), her sustained engagement with Browning’s work complicates this dynamic. Instilled with pathos, her recitation and reflective essay revealed that she had spent a significant amount of time with the poem, studying its cadence and emotional beats and contemplating its layered racial appropriation.

Learning from the experimental launch of the project in Fall 2022, I revised the “Narrating Victorian Poetry” assignment for Fall 2023 and rolled it out as a required assignment, in place of a midterm exam or essay, for the same Victorian literature survey course. Central to these revisions was my desire to expand my students’ knowledge of Victorian poetry beyond the familiar and overwhelmingly white faces of the literary canon.

This newest iteration of the assignment aimed to provide students with access to a greater diversity of Victorian authors while still promoting student choice as they broadened their understanding of the nineteenth century. Although students remained free to pursue their own interests in their poem selection, I also pointed them towards COVE’s “Works by and about People of Color” and provided them with a curated folder of suggested works, linked to our COVE anthology, that included historically marginalized poets, like Toru Dutt, E. Pauline Johnson, Amy Levy, and Michael Madhusudan Dutt.

To support this race-conscious approach to Victorian poetry, I dedicated class time to discussions of representation and appropriation, and we worked together to develop strategies for responsible recitation and critical reflection. These discussions developed organically out of in-class conversations regarding narratorial styling. And although this relatively informal approach worked well with my Fall 2023 students, I want to provide future sections with a more structured framework. To better introduce this discussion in the future, I will utilize one of our course texts to illustrate how considerations of identity shape narrative performance. As a class, we will listen to the opening pages of three different audiobook editions of Seacole’s Wonderful Adventures, performed by three different narrators.

The first is the edition that my students are most likely to encounter when they search for the assigned readings on YouTube (a popular platform for undergraduate audio readers): a Librivox recording read by Cori Samuel in 2014. The second is Yasmin Mwanza’s reading of Seacole’s work for Penguin Classics (2020), and the third is an Amazon Classics edition read by Debra Michaels (2021). Michaels and Mwanza are both professional actors and narrators and women of color, and they both chose to perform Seacole’s first-person narrative in a Jamaican accent; whereas Samuel is a white woman who reads Seacole’s work in her own, British accent.

Following our listening session, I will build on James F. English’s observation that the issues presented by racial representation, appropriation, and vocal stereotyping in audiobook narration can be approached as “teachable controversies” (423), and I will lead a group discussion that grapples with how to ethically narrate the work of an author whose positionality is not shared by the student reader. To do that, I will provide them with this prompt from English: “Every vocal performance of a novel is an interpretation, a reading as well as a reading out loud [...] Should we avoid white actors’ performance of work by writers of color generally? What about vice versa? How should characters’ gender and sexuality be vocalized?” (422-23).

Moreover, to English’s questions, I will add: What about class or disability? Guided by these questions, my students and I will work through the complexities of embodying someone else’s voice, the negotiation of accessibility (i.e., free Librivox recordings) versus attempted authenticity (via paid professional actors), and the intersecting dynamics of representation, copyright, and corporate performative activism. Ultimately, I will advise them to recite their chosen poem in their own voice and critically reflect upon how their positionality might intersect with, shape, or reconfigure how a future audience might interpret the poem.

Besides my efforts at introducing my students to a more diverse body of Victorian poets, another major revision focused on the written component of the assignment and my desire to promote the relevance of academic research to non-traditional essay assignments. Like my Fall 2022 students, my Fall 2023 students were asked to produce an accompanying narrator’s statement reflecting on their process of studying and reciting the poem.

However, this statement was expanded to comprise a longer reflective essay (5-6 pages) that describes their research into their chosen poem’s historical and critical context, meditates on their performance and how this context shaped their narration, and considers how the act of recitation shaped their aesthetic and affective response. To prepare my students for the essay’s research requirement, I invited a UVU research librarian specializing in literature to visit our class and demonstrated how to evaluate scholarly and non-scholarly sources.

While this latest version of the assignment maintains the written component, on the whole it decenters the traditional literary analysis essay in favor of a multimodal project that better accommodates students with varying levels of academic experience and preparation. For example, the reflective nature of the essay allows for less formulaic forms of writing than traditional academic essays, which predicate success on previous academic training and the reproduction of the white supremacist cudgel that is “standard English” (for more on this, see Milsom). Instead, students demonstrate their understanding and interpretation of the text through describing the choices they made in pacing, inflection, tone, and other embodied modes of expression.

Evaluation, in the case of these reflective essays, is focused on the specificity and depth with which students are able to discuss their narratorial styling of the poem, their research into the poet and poem’s historical and critical context, and how this context framed their experience of giving voice to the text. In deprioritizing the formal essay elements that mark success in more traditional forms of written work, this assignment lowers the stakes for students who have historically struggled in the English classroom and quells anxieties about the “correct” way to interpret a text that often serve as barriers to literary interest and engagement.

Additionally, the unconventional shape of this project allows for more creative expression. For example, one student felt that Amy Levy’s “A Wall Flower” – which is set at a dance – deserved a score, and her recitation was accompanied by carefully chosen and timed background music. It also allowed me to better understand the challenges my students navigate as they complete their coursework. Many students disclosed that they recorded their recitations in their cars, as this was the only space where they could ensure privacy and silence.

Given that many audiobooks are read during commutes to work and school, and that nineteenth-century poetry was imbricated with everyday life and encountered in a variety of settings both public and private (Behlman and Moy), this choice was apropos. However, it also served as a good reminder that my commuter campus is populated by students for whom a room of one’s own is a luxury. Another student shared her trepidation towards the assignment as someone with dyslexia:

As I did on the research and read the assigned poem (which I must admit I read well over a hundred times), I began to notice a transformation within myself. I was reading with increasing confidence, making fewer and fewer mistakes. My first attempt at recording my reading, compared to the final version I turned in, showed a striking contrast. It was a revelation for me. I had been proven wrong yet again. Researching, understanding, and consistent practice were precisely what I needed to make this poem resonate fully with me.

Through her candor and vulnerability, this student makes a good case for creating space in a semester-long survey for the concentrated study of a single text. Doing so might just allow students to discover points of resonance (to borrow my student’s apt term) in otherwise marginalized texts, as well as make these texts more accessible for future readers through the students’ recorded recitations. With their permission, their recordings can be shared with future sections of Victorian literature. And with some additional preparation and recording instruction, they might contribute to Librivox’s weekly and fortnightly poetry project.

Ultimately, this assignment attempts to challenge the primacy of the print text as the benchmark for academic assessment and engagement. In doing so, it invites us to reconsider the intellectual and creative value of oral/aural assignments and self-directed research, and it promotes authentic learning and metacognition through embodied explorations of positionality, identification, and representation. It also takes seriously the project of accessible and antiracist assignment design. Through its engagement with the aurality of nineteenth-century poetry, this assignment introduces students to authors and works regularly excluded from anthologies and surveys of Victorian literature, encourages sustained engagement and critical reflection on the affinities and displacements of reading and reciting Victorian poetry in the contemporary classroom, and makes these texts more accessible for multimodal readers through the student recitations.

Furthermore, situated in the context of my audiobook-inclusive course, this assignment invites my students to consider the relationship between mediation, narration, and authorship, and thus produces more insightful discussions of the narratorial dimensions of our course texts, which extend to other forms of media encountered by students outside of the classroom. In sum, this assignment undisciplines traditional modes of academic assessment, challenges conventional ideas about the nature of reading and writing, and attempts to unsettle the essay’s role in replicating the structures of power that safeguard institutional white supremacy.

Works Cited

Behlman, Lee, and Olivia Loksing Moy. “Introduction: Defining Victorian Verse.” Victorian Verse: The Poetics of Everyday Life, edited by Lee Behlman and Olivia Loksing Moy, Palgrave Macmillan, 2023.

Boyle, Elizabeth A., et al. “Effects of Audio Texts on the Acquisition of Secondary-Level Content by Students with Mild Disabilities.” Learning Disability Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, 2003, pp. 203–14.

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Introduction: Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Victorian Studies, vol. 62, no. 3, Spring 2020, pp. 369–91.

Clinton-Lisell, Virginia. “Listening Ears or Reading Eyes: A Meta-Analysis of Reading and Listening Comprehension Comparisons.” Review of Educational Research, vol. 92, no. 4, 2022, pp. 543–82.

Cohen, Michael C. The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Deniz, Fatma, et al. “The Representation of Semantic Information Across Human Cerebral Cortex During Listening Versus Reading Is Invariant to Stimulus Modality.” The Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 39, no. 39, 2019, pp. 7722–36.

English, James F. “Teaching the Novel in the Audio Age.” PMLA, vol. 135, no. 2, 2020, pp. 419–26.

Gregory, Melissa Valiska. “Race and the Dramatic Monologue.” Victorian Studies, vol. 62, no. 2, 2020, pp. 213–18.

Keen, Suzanne. Empathy and the Novel. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kreilkamp, Ivan. Voice and the Victorian Storyteller. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

McCleary-Jones, Voncella. “Learning Disabilities in the Community College and the Role of Disability Services Departments.” Journal of Cultural Diversity, vol. 14, no. 1, 2007, pp. 43–47.

Milsom, Alexandra L. “Assessing and Transgressing: On the Racist Origins of Academic Standardization.” Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, 2021.

Nadeau, Ashley, and Jessica Craig. “Reading Transformed: Measuring the Impact of Audiobooks and Transmedia on Learning in the Victorian Literature Classroom.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, vol. 47, no. 1, 2025.

Nesbit, Kate. “‘Taste in Noises’: Registering, Evaluating, and Creating Sound and Story in Jane Austen’s Persuasion.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 47, no. 4, 2015, pp. 451–68.

Robson, Catherine. Heart Beats: Everyday Life and the Memorized Poem. 2012.

Rubery, Matthew. “Play It Again, Sam Weller: New Digital Audiobooks and Old Ways of Reading.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 13, no. 1, 2008, pp. 58–79.

Rubery, Matthew, and Matthew Rubery. “Introduction: Talking Books.” Audiobooks, Literature, and Sound Studies, Routledge, 2011, pp. 1–21.

Singh, Anisha, and Patricia A. Alexander. “Audiobooks, Print, and Comprehension: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” Educational Psychology Review, vol. 34, 2022, pp. 677–715.

“Utah Valley University Enrollment Reaches Record 44,653 Students, a 3.61% Increase from Fall 2022.” Utah Valley University, 17 Oct. 2023.

“Utah Valley University Fall Enrollment Tops 43,000 Students.” Utah Valley University, 17 Oct. 2022.

Beyond the Essay Series

This cluster challenges instructors to think beyond the traditional essay often used in Victorian studies classrooms by providing examples of multimodal and/or public-facing assignments. Through creative assignment design, this cluster demonstrates that students can participate in the undisciplining of the field via projects that encourage critical and multimodal remaking, engagement, and communication, as well as those that reimagine and expand the audience of Victorian studies.

Developer Biography

Ashley Nadeau is an associate professor in English at Utah Valley University in Orem, UT. Her current research project examines the role of audiobooks in undergraduate literary studies and studies in the Victorian novel. When not thinking about audiobooks, she studies the relationship between the social and architectural histories of built public space and the Victorian literary imagination. Her work has appeared in Victorian Literature and Culture, Victorians Journal, The Gaskell Journal, and Modern Language Studies.

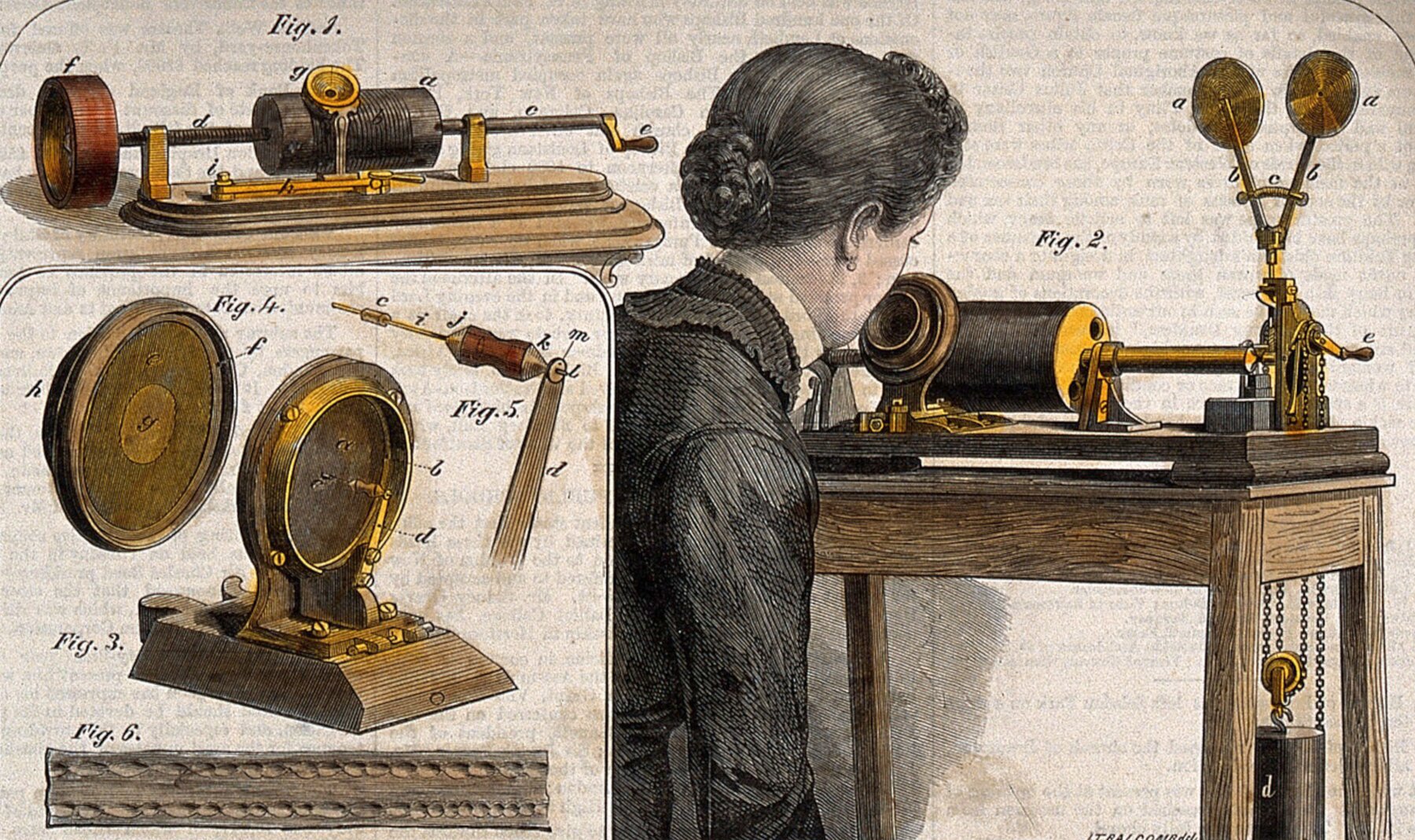

Tile/Header Image Caption

Balcomb, J. T. “Acoustics: An Edison Phonograph with a Carbon Microphone.” 1878. 47037i, Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark..Page/Assignment Citation (MLA)

Ashley Nadeau, dev. “Audio Encounters with Victorian Poetry.” Jacqueline Barrios, peer rev.; Sophia Hsu, Jude Fogarty, assess. guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2025, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/assignments/audio_encounters.html.