Colonial Landscapes and Travel Narratives

Lesson Plan Production Details

Goals, Questions, and Usage

A landscape presupposes a separation between nature and its beholder. “The very idea of landscape,” as Raymond Williams claims, “implies separation and observation.” It requires the presence of the “self-conscious observer,” who attentively looks at a site with a particular awareness of his position defined in society (120–21). This position is often that of the white, bourgeois, European man who perceives the land as a distanced spectator rather than as a person with intimate knowledge of the land. Colonial landscapes are especially marked by this imperialist distance.

According to Simon Gikandi, nineteenth-century English travelers described colonial landscapes in such a way that indicated a desire for totalization. Given that these descriptions consistently used the metropole as a reference point, these travelers fostered a perception of foreign lands that enabled them to establish their own identities. Mary Louise Pratt, however, argues that colonial landscapes are shaped by the “transculturation” that occurs in “contact zones,” where colonial distance and dominance can be subverted as colonial and indigenous cultures meet and change each other (4–7). Landscape is, as W. J. T. Mitchell contends, “a medium [...] for communication between the Human and the non-Human” as well as “a process by which social and subjective ideas are formed” (15, 1). The possibility exists, then, for colonial landscapes to transform imperialist distance into a portal for communicative construction.

This lesson plan critiques the distanced perspective that white settlers used in nineteenth-century travel narratives to characterize African landscapes. It also examines the process of looking in a context that displaces the imperialist separation of the observer and the observed by revealing the interconnected networks of human viewers and nonhuman vistas. This lesson plan thus combines postcolonial and environmental approaches to interrogate the nature/culture binary, which was used to support the dehumanization of colonized natives and the capitalist exploitation of indigenous labor and resources.

Possible questions that students might explore in this lesson plan include: What features do the nonfictional records of colonial environments have in common? How does the aestheticization of colonial landscapes both promote and challenge imperialism? How do the travelers’ encounters with animals and plants work for or against colonial taxonomy? To what extent do these travel narratives and images establish or blur the distance between the human spectator and their physical surroundings? How do fictional and nonfictional travel narratives imagine nineteenth-century Africa along the continuum of humans and environments?

Suggested Materials

Below are suggested primary texts and images that might help students analyze the colonial dynamics of African landscapes, both written and visual. These suggestions and the accompanying annotations are not meant to be comprehensive. Rather, I provide them to give instructors a brief sense of the possible materials, topics, and questions they might explore with their students. Any corrections or further suggestions are welcome.

Primary Texts

Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. Edited by Paul Armstrong, 4th ed., Norton, 2005.

This fictional travel narrative investigates the complexity of imperialism through Marlow’s observation of wilderness and Black natives in the Congo. Students can discuss how the implied position of the narrators in the travel and frame narratives – Marlow’s perspective as a separate, colonial “seeing-man” from Europe and the first person anonymous narrator who conveys the story second hand – shapes the reader’s understanding of the hierarchical binaries constituting imperialism (e.g., wilderness vs. civilization, the Black woman vs. the Intended) as a precarious discourse. Students can also critique this implied position as it manifests in the racist aestheticization of the landscapes of the Congo River.

Horton, James Africanus B. Physical and Medical Climate and Meteorology of the West Coast of Africa with Valuable Hints to Europeans for the Preservation of Health in the Tropics. John Churchill & Sons, 1867.

Although this book, written by a Krio surgeon, is not technically a travel narrative, it deserves attention, as it describes the material components of the African environment and their effects on human bodies and related diseases from an indigenous, medical perspective. It is a scientific account of African climate that provides “the detailed causes of the diseases of the coast, and the prophylactic measures which are necessary for their amelioration” (vi). The book starts with the “Definition of the Term Climate” (chapter 1), reviews the “four seasons: the rainy, harvest, harmattan, and summer” (15), and discusses the “effects of great heat on the intellectual faculties of men” (66). This book may be useful for a course on colonial environments engaging with the medical and environmental humanities.

Livingstone, David. Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript, directed by Justin D. Livingstone and Adrian S. Wisnicki, first ed, peer rev. and revision, Livingstone Online, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2019-20.

This text is Livingstone’s most famous written work. It details his time as a resident missionary as well as his famous transcontinental expedition across Africa. See Justin Livingstone’s article “The Meaning and Making of Missionary Travels” for a brief review of the ambivalence characterizing the book’s stance on imperialism. According to Justin Livingstone, Missionary Travels reads initially like an imperialist discourse that narrates the explorer’s adventures in South Africa and encounters with local tribes, animals, and terrain that appear easily conquerable. Yet a close scrutiny of David Livingstone’s original manuscript reveals his “relativist approach to local cultures and his resistance to racial stereotypes,” which complicate the book’s reception as the work of empire (286).

Pringle, Thomas. Narrative of a Residence in South Africa. 1834. New ed., Tegg, 1851.

In this text, the Scottish poet and abolitionist writes about his years spent in South Africa. The perspective is Evangelical and sympathetic. At the beginning of the book, he calmly observes his “journey through the wilderness of jungle,” noting the aesthetic qualities of the landscape: “[t]he scenery through which we passed was in many places of the most picturesque and singular description” (9, 11). Pringle’s description of natives and animals (43–55) may read like an objective, distanced taxonomy that translates the unknown into graspable, Western knowledge. But might it be read otherwise? Indeed, one could interpret Pringle’s exposure to the broad spectrum of species and native tribes in South Africa – an exposure that challenges his restrictive residence in Europe – as him extending his self-awareness to the planetary scale, as he embraces his relationality across the globe.

Trollope, Anthony. South Africa. 4th ed., 2 vols., Chapman and Hall, 1878. Volume 1. Volume 2.

In this book, Trollope records his travels to the South African colonies, including the Cape Colony, Natal, the Transvaal, Griqualand West, and the Orange Free State. With each place he visits, Trollope discusses the history of colonization, customs, and diverse races inhabiting the region. The perspective is quite imperialist, endorsing English supremacy and disparaging the natives’ incompetence. As if to demonstrate an aesthetic appreciation, Trollope often uses words such as “pretty,” “picturesque,” and “beauty” when he prepares to describe African landscapes. However, the actual descriptions do not affirm this view. Even when he introduces “picturesque” South African sites, the description is full of factual details and imperialist comparisons with European landscapes. There is no sincere admiration.

Visual Materials

I recommend analyzing the following images alongside famous landscape paintings of the eighteenth century, such as those by Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. See Williams’s chapter “Pleasing Prospects” in The Country and the City, pp. 120–26 for more potential landscape paintings.

A Woman Attacked by a Crocodile Emerging from the Water, in Central Africa. 1874. Wellcome Library, 561388i.

This illustration is based on a scene in Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and its Tributaries; and of the Discovery of the Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858-1864, Livingstone’s travel narrative about his second journey across the African continent published in 1865. It could be paired with Val Plumwood’s essay “Being Prey” (also known as “Surviving a Crocodile Attack”). This essay destabilizes the idea of human mastery over nature, as implied in colonial landscapes, by revealing the shared vulnerability of humans in the animal food-chain. Some questions to consider with this image include: How does the image of the woman attacked by a crocodile complicate the cross-species encounter typically found in colonial hunting visuals? To what extent does this image challenge the white observer’s aloof position? How does this image, which is both threatening and aestheticized, affirm or contest the distance between nature and its beholder that is inherent in the structure of landscapes?

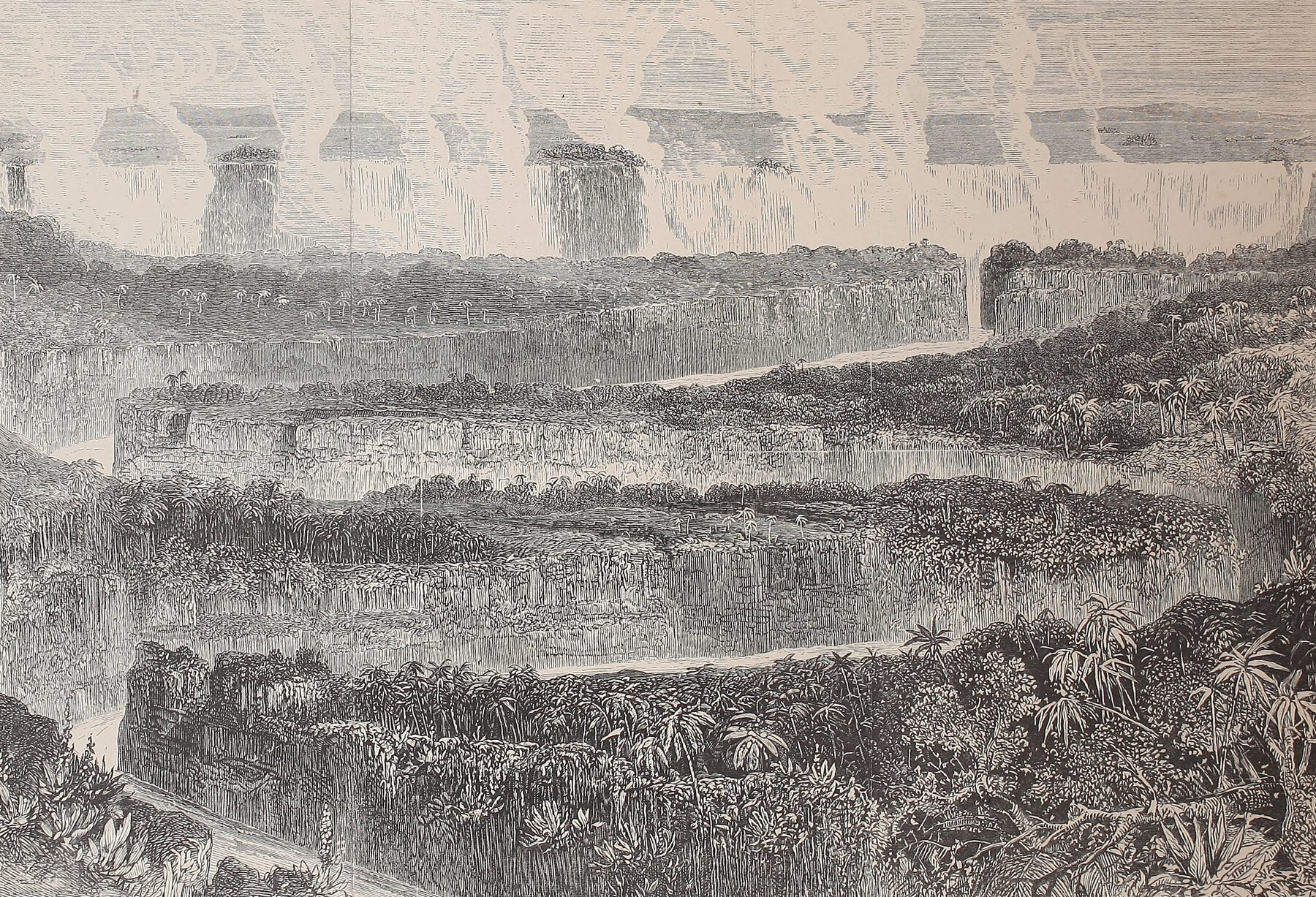

“Bird’s-Eye View of the Great Cataracts of the Zambesi (Called Mosioatunya, or Victoria Falls) and of the Zigzag Chasm below the Falls through Which the River Escapes.” Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries and of the Discovery of the Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858-1864, by David Livingstone and Charles Livingstone, John Murray, 1865, frontispiece.

This image epitomizes the colonial aestheticization of African landscapes for the pleasure of the white male traveler, who seeks triumphant mastery over indigenous nature. Students can discuss the violence implied in the bird’s-eye view of Victoria Falls, the message conveyed by the layout of the falls and trees, and the significance of the observer’s disembodied presence.

David Livingstone’s Steamboat, the Ma-Robert, on the Zambezi River; Crocodiles in the Foreground. Wellcome Library, 561391i.

Ma-Robert was a steamboat that Livingstone employed for his expedition to the Zambezi in 1858–62. The layout of the scene mimics the typical country landscape found in eighteenth-century landscape paintings. Yet the abundance of animals (crocodiles and birds) and their central positioning challenge the colonial aestheticization of African nature by foregrounding what is usually marginalized: animal life.

Man on Horseback Accompanied by Men with Spears; Man Kneeling Below Tree. Travels in the Interior of Africa, by Mungo Park, Adam and Charles Black, North Bridge, 1858, frontispiece.

The Scottish explorer Mungo Park left records of his expedition to the Niger and encounters with African tribes in his popular book, Travels in the Interior of Africa, the first edition of which was published in 1799. The frontispiece of this book depicts his initial sighting of the Niger, which he describes as “the long sought for majestic Niger, glittering to the morning sun.” The title page, which features Park himself left alone after being looted by gangsters, portrays the white man as hopeless and forsaken in a wild forest, thus countering the triumphant, distanced perspective of the white “seeing-man.” For Park’s “sentimental travel writing,” see Pratt’s chapter, “Anti-conquest II: The mystique of reciprocity,” in her book Imperial Eyes, pp. 69–85.

Secondary Materials: Criticism on Country and Imperial Landscapes

Gikandi, Simon. Maps of Englishness: Writing Identity in the Culture of Colonialism. Columbia University Press, 1996.

Livingstone, Justin. “The Meaning and Making of Missionary Travels: The Sedentary and Itinerant Discourses of a Victorian Bestseller.” Studies in Travel Writing, vol. 15, no. 3, 2011, pp. 267–92.

Mitchell, W. J. T. Landscape and Power. 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2008.

Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. Oxford University Press, 1973.

Secondary Materials: Criticism on Colonial Environments in Postcolonial, Environmental, African American, Indigenous, and Victorian Studies

Aguirre, Robert D. Informal Empire: Mexico and Central America in Victorian Culture. University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Banerjee, Sukanya, et al. “Introduction: Widening the Nineteenth Century.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 49, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1–26.

Bergner, Gwen. “Introduction: The Plantation, the Postplantation, and the Afterlives of Slavery.” American Literature, vol. 91, no. 3, 2019, pp. 447–57.

Buell, Lawrence, et al. “Literature and Environment.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 36, 2011, pp. 417–40.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. Allegories of the Anthropocene. Duke University Press, 2019.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth, et al., editors. Global Ecologies and the Environmental Humanities: Postcolonial Approaches. Routledge, 2015.

Griffiths, Devin, and Deanna K. Kreisel. “Introduction: Open Ecologies.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 48, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–28.

Heise, Ursula K. “Afterword: Postcolonial Ecocriticism and the Question of Literature.” Postcolonial Green: Environmental Politics and World Narratives, edited by Bonnie Roos and Alex Hunt, University of Virginia Press, 2010, pp. 251–58.

---. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Hensley, Nathan K., and Philip Steer, editors. Ecological Form: System and Aesthetics in the Age of Empire. Fordam University Press, 2018.

MacDuffie, Allen, and Aubrey Plourde. “Introduction.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 62, no. 2, 2020, pp. 123–27. Appears in a special journal issue on “Victorian Environments.”

Miller, John. “Postcolonial Ecocriticism and Victorian Studies.” Literature Compass, vol. 9, no. 7, 2012, pp. 476–88.

Nixon, Rob. “Environmentalism, Postcolonialism, and American Studies.” Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Harvard University Press, 2011, pp. 233–62.

Taylor, Jesse Oak. “Wilderness After Nature: Conrad, Empire, and the Anthropocene.” Conrad and Nature, edited by Rebozo Lissa Scheider et al., Routledge, 2018, pp. 21–42.

Voskuil, Lynn. “Victorian Plants: Cosmopolitan and Invasive.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 49, no. 1, 2021, pp. 27–53.

Developer Biography

Ji Eun Lee is a BK21 postdoctoral fellow in Interaction English Studies in the Era of AI at Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU) in Seoul, South Korea. She received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English Language and Literature from Seoul National University and her Ph.D. in English from UCLA. Her scholarship investigates nineteenth-century British literature, environmental humanities, medical humanities, and postcolonial studies. Her first book-in-progress, Walking London: Urban Gaits of the British Novel, examines the rise of the novel in relation to the emergence of the city through the perspective of a city-walker, whose gaits are shaped by the material environment and are translated into narrative movements. She also works on contemporary Anglophone literature and has published on Kazuo Ishiguro and Chang-rae Lee in Texas Studies in Literature and Language and American Studies, respectively.

Header Image Caption

“Bird’s-Eye View of the Great Cataracts of the Zambesi (Called Mosioatunya, or Victoria Falls) and of the Zigzag Chasm below the Falls through Which the River Escapes.” Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries and of the Discovery of the Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858-1864, by David Livingstone and Charles Livingstone, John Murray, 1865, frontispiece. Public domain.

Page/Lesson Plan Citation (MLA)

Ji Eun Lee, les. plan dev. “Colonial Landscapes and Travel Narratives.” Carolyn Betensky, Melissa Free, Cherrie Kwok, collab. peer revs.; Sophia Hsu, les. plan clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2021, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/lesson_plans/africa_colonial_landscapes.html.