Ethiopianism

Lesson Plan Production Details

Goals, Questions, and Usage

Variously a movement, an ideology, and a collection of assorted concerns, Ethiopianism was loosely centered around the idea of African greatness. It drew from the Bible (Psalms 68:31) and the history of African empires. It had strains in the United States, West Africa, and southern Africa. It might encourage a diasporic return to Africa, religious separatism (the creation of Black churches), or economic self-reliance. In most iterations, it presaged Pan-Africanism. Energizing and uniting Africans and those of African descent, Ethiopianism terrified many whites. The selection of texts below, from British, American, Rhodesian, Ghanaian, and West Indian writers, will enable students to explore Ethiopianism from multiple angles. Topics of discussion might include cultural exchange, religion and the novel, Pan-Africanism, proto-nationalism, racism, imperialism, genre, and resistance. Students might consider what kinds of connections these texts seek to establish, compel, or disavow – particularly but not only between peoples and places – and how they do so. The lesson plan would work well in a course on the Black Atlantic, the trans-Atlantic, Pan-Africanism, the British empire, or South Africa as well as in a more thematic course, such as one on resistance.

Suggested Materials

Primary Materials *

* Note: Items listed in chronological order in this section.

African Civilization Society. “(1858) Constitution of the African Civilization Society.” Blackpast, 2009.

The African Civilization Society was founded by Henry Highland Garnet, an American abolitionist, minister, and former enslaved person, who encouraged Black Americans to emigrate to Africa.

Booth, Joseph. Africa for the African. n.p., 1897.

A white English missionary who spent significant time in New Zealand, Australia, and Africa (and also traveled to the United States), Booth supported African self-rule and urged Black Americans to help bring that about. He directly influenced John Chilembwe, who organized, and died in, a 1915 rebellion against British colonial rule in Nyasaland (modern-day Malawi).

- Turner, Henry McNeal. “Emigration.” 1 Apr. 1900. Black Nationalism in America, edited by John H. Bracey et al., Bobbs-Merrill, 1970, p. 176.

- ---. “The Negro Has Not Sense Enough.” 1 July 1900. Black Nationalism in America, edited by John H. Bracey et al., Bobbs-Merrill, 1970, pp. 172–75.

Jones, Roderick. “The Black Peril in South Africa.” The Nineteenth Century and After, vol. 55, no. 327, May 1904, pp. 712–33.

Written by a close friend of John Buchan, this article in a widely circulated periodical describes Ethiopianism as a “quasi-religious,” “anti-white movement” (718, 716). Its title refers to a slippery but pervasive specter, ranging from a Black political majority to a Black revolution, from miscegnation to the rape of white women by Black men, which whites in southern Africa often invoked.

Gouldsbury, [Henry] Cullen. God’s Outpost. Nash, 1907.

Written by a British South Africa Company administrator, this very early Rhodesian novel includes a subplot in which “an apostle of the Ethiopian Mission” attempts to organize a rebellion against white rule (271). The apostle’s argument is similar to that of the African leader of John Buchan’s Prester John, who describes “a picture of the overthrow of the alien, and the golden age which would dawn for the oppressed” (ch. 11): “To-day in this continent, we outnumber the white men by half a million to one, and once we learn to combine, nothing can withstand us. The land shall run red with blood, their blood. [...] [T]he day will come when we will deny them the franchise, and be ourselves a law unto ourselves” (Gouldsbury 269). Note: Melissa Free can provide excerpts from this hard-to-get novel.

Buchan, John. Prester John. 1910. Project Gutenberg, 1996.

This adventure novel, written after Buchan spent two years as a colonial administrator in southern Africa, is narrated by Davie Crawfurd, a nineteen-year old Scotsman, who goes to work as a shopkeeper in a remote part of southern Africa. It takes its title, however, from John Laputa, a charismatic, American-educated, widely traveled Christian Zulu, who leads a large-scale, carefully coordinated indigenous rising. A “roving evangelist” who “talked Christianity to the mobs” and African nationalism to their leaders, Laputa takes the name “Prester John” from the mytho-historical Christian priest-king of Abyssinia (ch. 7). Representing both the threat of African nationalism and its futility, Laputa is a highly unusual figure in contemporary British writing.

Hayford, J. E. Casely. Ethiopia Unbound: Studies in Race Emancipation. C.M. Phillips, 1911.

This philosophical novel set in both the Gold Coast and England centers on discussions between a Ghanaian man and an Englishman. It is among the first novels in English by a Black African.

Garvey, Marcus. Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey. 1925. Ravenio Books, 2015.

In “The True Solution of the Negro Problem – 1922,” Garvey argues that people of African descent in the West Indies (where he was born) and the United States (to which he emigrated) have no future in the “Western hemisphere” because they are oppressed – and outnumbered – by whites (ch. 4). They should therefore “enter into a common partnership to build up Africa in the interests of our race,” as he writes in “The Dream of a Negro Empire” (ch. 4).

Critical Materials

Free, Melissa. “‘There Will Be No More Kings in Africa’: Foreclosing Darkness in Prester John.” Beyond Gold and Diamonds: Genre, the Authorial Informant, and the British South African Novel, State University of New York Press, 2021, pp. 135–54.

This analysis of Prester John provides a short summary of Ethiopianism in Buchan’s novel, in southern Africa, and as a transcontinental movement. It also explains the significance of the mytho-historical figure Prester John, a Black Christian king, to the indigenous rising that is at the heart of the novel. In depicting indigenous strength as contingent on a single charismatic leader and the fetish that legitimizes him, Buchan’s novel, Free argues, acknowledges only to destroy the dreaded swell of organized, collective African nationalism. Though it begins as an imperial romance, by the time it concludes there is no treasure left to unearth, no enemy to oppose, no darkness to withstand.

Kalu, Ogbu U. “Ethiopianism and the Roots of Modern African Christianity.” World Christianities, c.1815-1914, Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 576–92.

Providing religious, political, and social contexts, this relatively short article is a comprehensive overview of Ethiopianism’s “three broad strands: in African-American diasporic experience, West African manifestations and southern African genre. In all incarnations, it fuelled black nationalism” (581).

Wittenberg, Hermann. “Race, Resistance and Translation: The Case of John Buchan’s UPrester John.” English Studies in Africa, vol. 54, no. 1, 2001, pp. 1–10.

A popular school textbook in Britain and the Commonwealth, Prester John was read by both the colonizer and the colonized. Wittenberg explains that while the novel “[fit] well into a cultural milieu shaped by Rider Haggard, Treasure Island, and the Boy Scouts,” it has also been read as an anticolonial novel (6). His main focus is the translation of Prester John into Zulu in 1958 as “a complex form of negotiation [between] resistance [and] collaboration” (6).

Developer Biography

Melissa Free is Assistant Professor of English, Affiliate Faculty in the School of Social Transformation, and Barrett Honors College Faculty at Arizona State University. Her monograph, Beyond Gold and Diamonds: Genre, the Authorial Informant, and the British South African Novel, was published by State University of New York Press in 2021. She is the editor of a Broadview Anthology of British Literature edition, The Dead and Other Stories, by James Joyce. Her scholarly articles and book chapters have appeared in such places as Victorian Literature and Culture, Victorian Studies, Genre, and The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Literary Culture, edited by Juliet John. Her primary academic interests are Victorian literature and culture, twentieth-century British literature and culture, postcolonial studies, gender and women’s studies, and genre studies.

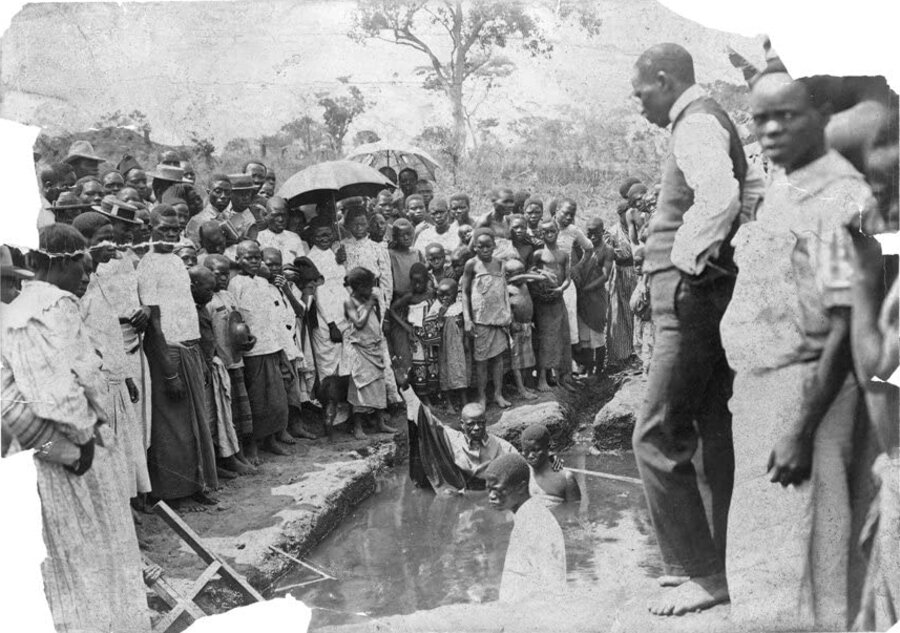

Header Image Caption

Baptism by John Chilembwe in Liberia or Malawi. c.1900-15. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LOT 12573 <item> [P&P]. No known restrictions on publication.

Page/Lesson Plan Citation (MLA)

Melissa Free, les. plan dev. “Ethiopianism.” Carolyn Betensky, Cherrie Kwok, Ji Eun Lee, collab. peer revs.; Sophia Hsu, les. plan clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2021, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/lesson_plans/africa_ethiopianism.html.