Southern Africa, 1820–1930

Lesson Plan Production Details

Goals, Questions, and Usage

Beginning with British settler poetry and concluding with the earliest full-length novel in English by a Black South African, this lesson plan explores issues of race, belonging, gender, and agency. It covers the period between the arrival of five thousand British settlers in the early 1820s and the first two decades that followed the 1910 formation of the Union of South Africa. It includes fiction or poetry (and in most cases also non-fiction) by six authors, who are variously Scottish, British South African, English, Zulu, and Tswana. Students could be asked to consider settler identity, including its relationship to indigeneity and the metropole. They could reflect on Olive Schreiner’s changing attitude to Boers and Black Africans. They could compare indigenous and white writers’ depictions of conflict, race, space, religion, gender, and history.

The lesson plan is designed to be flexible. Instructors could select just a few of the suggested texts if they want to teach a unit on southern Africa rather than a whole course – in a course on literature of the British empire in the long nineteenth century, for instance. They could pair one of the suggested texts with a later South African text: An African Tragedy with Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country (1948), which both explore the perils of city life for Black South Africans; or Pringle’s Narrative of a Residence in South Africa with Zoë Wicomb’s Still Life (2020), an historical novel about Pringle told from multiple perspectives, including that of Mary Prince, a formerly enslaved West Indian-born woman whose narrative he edited.

Any of the suggested texts could bring southern Africa into a conversation that is not primarily about southern Africa. For example, Pringle’s poetry could be included in a unit, a week, or even just a day on abolition poetry by William Cowper, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and others. Schreiner’s short story “Eighteen-Ninety-Nine” could be paired with a short story from the American Civil War, perhaps one focused on the women left behind when the men go off to fight or one that is sympathetic to “the other side.” Bessie Marchant’s Molly of One Tree Bend could be read alongside contemporaneous young adult fiction, such as Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), with which it has much in common, or pretty much anything by G. A. Henty. Mhudi could be compared to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958), which also depicts shifting power dynamics in nineteenth-century Africa.

Suggested Materials*

*Note: Items listed in chronological order in all the following sections.

Thomas Pringle

- “Song of the Wild Bushman.” 1825. The Poetical Works of Thomas Pringle, Edward Moxon, 1839, pp. 11–12.

- “The Kosa.” 1828. The Poetical Works of Thomas Pringle, Edward Moxon, 1839, pp. 13–15.

- “The Slave Dealer.” 1828. The Poetical Works of Thomas Pringle, Edward Moxon, 1839, pp. 58–59.

- “The Bechuana Boy.” 1830. The Poetical Works of Thomas Pringle, Edward Moxon, 1839, pp. 3–8.

Narrative of a Residence in South Africa. 1834. New ed., Edward Moxon, 1835.

Pringle’s first-hand account offers insight into settler colonial life.

Olive Schreiner

The Story of an African Farm. 1883. Project Gutenberg, 1998.

Written when Schreiner was a governess in her late teens, this was the first internationally successful South African novel and the first New Woman novel. Foregrounding issues of authority and belonging, it offers a view into colonial life, critiques gender inequality, and experiments with narrative form.

Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland. 1897. Project Gutenberg, 1998, 2008.

This is a semi-religious, allegorical, anti-imperialist novella in which the protagonist, a soldier in Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company, eventually recognizes and rejects his former racism.

“The Supreme Question for South Africa: A Warning and An Appeal, ‘The Native Problem in South Africa.’” Review of Reviews, vol. 39, no. 230, Feb. 1909, pp. 138–41.

This short piece illustrates the change in Schreiner’s attitude towards Black South Africans since her writing of The Story of an African Farm, in which Black characters are a mere backdrop to settler colonial life. Having resigned from the South African Women’s Enfranchisement League because it had decided not to advocate for Black women, Schreiner here argues for the enfranchisement of Black Africans.

“Eighteen-Nintey-Nine.” 1923. Stories, Dreams, and Allegories, Victorian Women Writers Project, 2021.

Focused on a Boer mother who sees all her sons go off to war, this short story offers a sympathetic, even romanticized, view of the Boers, in stark contrast to The Story of an African Farm.

H. Rider Haggard

Cetewayo and His White Neighbors. 1882. Project Gutenberg, 2006.

In this work of nonfiction, Haggard discusses the Zulus and their king, Cetewayo. In addition, he describes tensions not only between Cetewayo’s “white neighbors,” the Boers and the British, but also between colony and metropole.

The Ghost Kings. 1908. Project Gutenberg, 2003, 2005.

This female colonial romance depicts female settler heroism in southern Africa in the leadup to the Great Trek (the migration of approximately ten thousand Boers inland from the Cape in the 1830s and 1840s). It is particularly interesting for its portrayal of mystical feminism – protective supernatural powers facilitated by female bonds across cultures – and female authority as well as its blending of history and romance. (On the female colonial romance and mystical feminism, see Melissa Free, “‘It Is I Who Have the Power’: The Female Colonial Romance,” Beyond Gold and Diamonds: Genre, the Authorial Informant, and the British South African Novel, State University of New York Press, 2021, pp. 61-105.)

Bessie Marchant

Molly of One Tree Bend. Butcher, 1910.

This short young adult novel follows the entrepreneurial and other adventures of its young colonial heroine in her second decade of life. As in Dhlomo’s An African Tragedy, the city in Marchant’s novel is a place of danger (particularly financially), but it is also a market for Molly’s growing business ventures. The novel is useful for discussing gender, race, and agency in a colonial context.

R. R. R. Dhlomo

An African Tragedy. Lovedale Press, 1928.

In the first novella in English by a Black South African, Dhlomo describes the dangers of city life for Black Africans. Leaving his village teaching job, the Zulu protagonist moves to Johannesburg to earn enough money to marry the woman he loves. He falls under the influence of drink and gambling, has sexual relationships with married women, gives his own wife a venereal disease – and as a result the child she soon births—and is ultimately murdered. The story, which has clear Christian overtones, ends with the man’s deathbed confession.

Sol T. Plaatje

Native Life in South Africa. King, 1916.

Passed just three years after the formation of the Union of South Africa, which did not guarantee voting rights to Black Africans, the 1913 Natives Land Act dispossessed them of almost all of their land. This trenchant critique is written by the founding secretary of what would become the African National Congress.

Mhudi. Lovedale Press, 1930.

The first novel in English by a Black South African, Mhudi was written in the late 1910s and early 1920s, though not published until 1930, as Plaatje struggled to find a publisher. It is self-consciously hybrid, using both African idiom and the English language; orality and the novel form; African storytelling techniques, such as songs, gossip, anecdotes, folktales, and proverbs, and European literary genres, like the epic and the romance. The influence of the female colonial romance is manifest most ostensibly in its courageous heroine who “thrice face[s] the king of beasts [a lion] and [ultimately] kill[s] one with her own hand” (47). Set during the Mfecane (the period of indigenous wars and power struggles that took place between roughly 1815 and 1840) and the Great Trek (the north- and eastward migration of approximately ten thousand Boers seeking to escape the reach of British authority, which took place in the 1830s and 1840s), Mhudi depicts warfare between the Matabele and other Black African peoples as well as cross-ethnic, cross-racial, and cross-cultural alliances.

Developer Biography

Melissa Free is Assistant Professor of English, Affiliate Faculty in the School of Social Transformation, and Barrett Honors College Faculty at Arizona State University. Her monograph, Beyond Gold and Diamonds: Genre, the Authorial Informant, and the British South African Novel, was published by State University of New York Press in 2021. She is the editor of a Broadview Anthology of British Literature edition, The Dead and Other Stories, by James Joyce. Her scholarly articles and book chapters have appeared in such places as Victorian Literature and Culture, Victorian Studies, Genre, and The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Literary Culture, edited by Juliet John. Her primary academic interests are Victorian literature and culture, twentieth-century British literature and culture, postcolonial studies, gender and women’s studies, and genre studies.

Header Image Caption

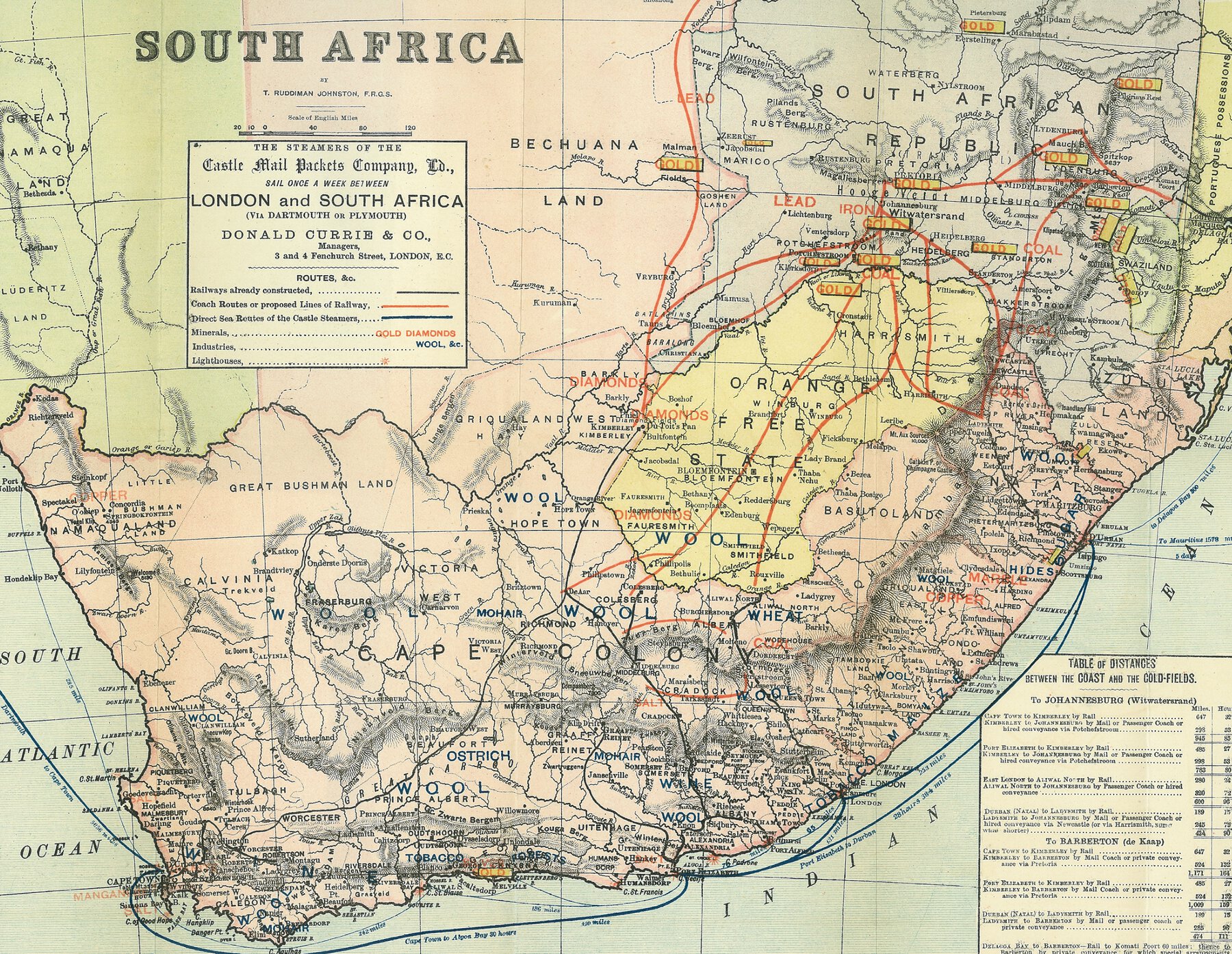

Map of Southern Africa. South Africa and How to Reach It by the Castle Line, by Edward P. Mathers, Simpkin, 1889, opp. contents page. Public domain. In describing southern Africa as “South Africa” when not referring specifically to the Union of South Africa (formed in 1910), the British elided the region’s indigenous territories and (for most of the nineteenth century) Boer republics.

Page/Lesson Plan Citation (MLA)

Melissa Free, les. plan dev. “Southern Africa, 1820-1930.” Carolyn Betensky, Cherrie Kwok, Ji Eun Lee, collab. peer revs.; Sophia Hsu, les. plan clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2021, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/lesson_plans/africa_southern_africa.html.