Teaching Romanticism and Victorianism in Palestine

Lesson Plan Production Details

Developers: Mohammad Sakhnini Contact, Sarah Copsey Alsader Contact, Lenora Hanson Contact

Lesson Plan Cluster Developer: Ryan D. Fong Contact

Lesson Plan Guide: Cherrie Kwok Contact

Webpage Developer: Ava K. Bindas

Cluster Title: Palestine in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Publication Date: 2023

Overview

This resource in this lesson plan cluster aims to familiarize teachers and students with the contemporary conditions in which teachers and students in Palestine learn.

The resource synthesizes multiple conversations that I conducted with teachers and academics in Ramallah, Jenin, Hebron, and East Jerusalem in the summer of 2022. The Palestinian Authority technically controls Ramallah and Jenin, but these cities are surrounded by areas that are under Israeli control and illegal settlements. The Palestinian Authority is also supposed to control Hebron, but extremist settlers and a large population of Israeli Defense Soldiers have illegally occupied the city since 1994.

East Jerusalem is a part of Palestine that has been illegally occupied by Israel since 1968. Since Palestinian instructors in English language departments teach survey courses and other courses in which canonical texts of the Romantic and Victorian periods are an important part of their students' education, this lesson plan cluster would not be complete without engaging this contemporary context. What is it like to teach texts that are often understood to be part of an Orientalizing project under the current settler colonial occupation of Palestine by Israel?

Recent attention has been drawn to the conditions faced by students of British studies in Israel, but engagements with the intellectual and day-to-day lives of those who have been colonized by Israel are completely absent in our fields.

It is worth hearing from Palestinian teachers and academics who continue to live through the ongoing effects of British imperialism and its support for the Zionist settler project that led to the Nakba as well as the present-day existence of the ethno-nationalist state of Israel on the historic land of Palestine, which was once a home for “Muslims, Christians, Jews, Samaritans, Arabs, and other indigeneized Palestinians” (Masalha 3). To that end, this “Situating Pedagogy'' resource shifts us away from the usual focus on historical and primary documents and toward the relevance of the experiences of Palestinian educators for how those of us outside of Palestine read and teach British Romantic and Victorian texts.

This resource contextualizes the conversations that I had with teachers and academics in Palestine and presents their approaches to teaching Romantic and Victorian literature under occupation, with the larger goal of situating these approaches through the framing of anti-colonial pedagogy. I want to be clear that this is my own framing: it is meant to ask us to reflect on our motivations and commitments to teaching about imperialism and colonialism in both the Romantic and Victorian periods of British literature, the extent that these topics inform who we take to be valuable interlocutors, and the relationships that we decide to build through our work as educators.

I have divided this material into three interrelated lesson plans, the third of which is forthcoming:

- Teaching Romanticism and Victorianism in Palestine

- The Question of Palestinian Literature Anti-Colonial Identity

- Anti-Colonial Practices in the Classroom (forthcoming)

I have removed names and institutional affiliations in order to anonymize and protect the identities of those whom I spoke to. Instead, I have used alphabetical letters to distinguish them from one another. All the interview transcripts have only been lightly copy-edited in order to preserve as much of the original voice as possible.

Teaching Romanticism and Victorianism

Undergraduate students at all three of the universities that I visited in the West Bank are required to take at least one course that surveys the major periods of British literature. These courses range from British literature courses to World Literature courses. Take a moment to let that set in.

Palestinian students are required to take these courses because, as A told me, “we were colonized by Britain. So that's why it's, you know, it's the traces of colonization. That's why we focus on British Literature as a canon as a kind of, it's like, subconsciously, we still feel that it's superior, we still feel like we should teach English literature, not any other, not French, not German, or international literature.” These students, who are still living under a settler colonial state put into place by the British empire, are reading the same texts that we in North America and Europe teach in our British literature classrooms.

Of course, many of us teaching about British colonialism through the literatures produced under its conditions often do so within the well-cushioned fantasy of a safe ideological remove. This is not the case for students and faculty who continue to live in the historical wake of Palestine's occupation by Great Britain and its public declaration of support for the Zionist movement in Palestine in 1917 (Khalidi, 158-162). That declaration formally established the collaboration between the British empire and a European Zionist project.

The partnership between the British empire and the Zionist movement manifests today as the routine invasion of Palestinian universities by the Israeli Defense Forces, arrests and incarceration of Palestinian students for the barest suspicion of political activity, and the difficulty – or impossibility – for Palestinian students to travel from one part of Palestine to the other. (Traveling to Jerusalem is almost certainly impossible for male Palestinian students and a challenge for female students.)

As many instructors noted, very few students want to take these courses. Understandably, they struggle with the significance of British literature to their own lives. Despite the colonial histories that shape British literature, all of the immediate pressures that Palestinian students are under today makes literature that is not connected to the literature of Palestinian resistance feel, as one instructor put it, pointless. This disconnect puts an immense pressure on teachers to work against the inherently colonial mentality of canonicity as well as the hierarchy that positions teachers as sources of knowledge that are ultimately abstracted from the lived realities of Palestinian students. B told me that:

At the start of the semester, I always have a general discussion. A lot of the students that we have don't like literature, they don't see the point in it. And I think rather than being offended by that, as some might, I always like to ask them, “why?” Because I don't want to sort of stand up there and proselytize and sermonize on how great literature is, and I get the whole thing. How is it relevant? Those students who are from the bloody refugee camp? You know, I mean, it's insulting just to say to them, you should. And so always at the start of every literature course, I say that if they think that that is pointless, why is that and how does it compare to other disciplines? (B, Personal conversation)

Thinking “Outside the University”

In a way, the challenge of revealing the relevance of literature that is historically and culturally removed from students is familiar to all instructors. Yet B mentions that some of her “students are from the bloody refugee camp,” and we are reminded of the specificity of her context. It is “insulting” to insist on the value of the literature she is supposed to teach them. What may seem vaguely obvious is brought into sharp focus here – that is, when one is teaching in a colonized land, what is of interest to students takes on a force that must transform the classroom:

I want to know what the students are interested in. So, one of the things that I do at the start of the course is I ask students about all the things that interest them outside of university and also academic disciplines that interest them. So, for example, you know, a lot of students will say things like they are interested in medicine or they're interested in crime and criminology. And so based on what they say I can prioritize certain literary works.

So, for example, I have a disturbing number of students who love watching serial killer movies. They love Element of Crime and also the psychology of crime. And so for that reason, when I started developing courses, I prioritize everything from Shakespeare's Richard the Third to Macbeth to Robert Browning's “Porphyria's Lover” and Poe's “Tell Tale Heart.” (B, Personal conversation)

B's orientation to teaching in this context is strikingly similar to perspectives that fall under the heading of student-centered pedagogy in the United States. Less analogous, however, are the contexts for this approach. One centers student interests in the context of settler colonial occupation, the other as both response to, and the effect of, neoliberalism in the United States.

What, then, can we learn from thinking of interests that come from “outside the university” as a practice undertaken against the everywhere-ness of death? What would it mean to situate interests through the colonial histories of the specific contexts in which we teach rather than through student-centeredness?

B's turn to the popularity of crime genres through texts by William Shakespeare, Robert Browning, and Edgar Allan Poe is reminiscent of Edward Said's argument about the worldliness of texts in The World, the Text, and the Critic (1983). Texts are worldly in the sense that they travel across space and time and are accommodated to different contexts; in B's case, it is to the context about which Said wrote so much. Her goal here isn't to teach her students “how great literature is”: rather, in each semester, what her students study is different depending on what it is that directs their interest away from the colonial insistence on death. As A put it to me:

When you live under occupation death is everywhere. And it is every day, we wake up and think about death. So, it's very hard to go and meditate and think about your intuitions and your inner side.

I do not know what it would look like for us to begin moving towards the relation between interests in general that are found outside of the university and anti-colonial pedagogy, but I think that we will only learn what this might look like in conversation with those who, like B, are actively in the midst of constructing that relation out of necessity. That these interests must come from outside of the university and outside of an enclosed canon reveals an important relationship between anticolonial pedagogy and continuous revision: class-by-class experimentation that is required in the interest of an education that does not reproduce a border between the inside and outside of the classroom and the university. This is an education, to borrow from the poet Rafeef Ziadah, in life.

What might our own teaching of the Romantic and Victorian texts that we share with B and her classroom look like if we began each semester similarly with such a discussion –n ot to win students over to literature, but out of an interest in learning something about the relationship between interests generated generally and teaching against colonialism's interest in the indifference of interests abstracted from its context?

C shared a similar perspective on teaching, but turned to the language of communication:

I think over the past few years I've been trying to not be a distant professor but am trying to get close, trying to listen to students and trying to know what's going on and to empathize and to understand and to be able to educate and teach them and guide them about several issues. [. . .] Students are a little bit resistant to communicate, especially in English, because they are not allowed to communicate in Arabic in the classroom. As an English teacher you have to communicate in English, so we have to get out of the box and exert more effort and try to teach students more than expected. (C, Personal conversation)

C emphasized the usefulness of classroom presentations in order for students to engage with what interests them as well as to facilitate their discussion with one another. He teaches survey courses in British Literature and World Literature and told me he enjoys teaching Mary Shelley's Frankenstein in particular. But he likes teaching communication courses with students the most:

Because, you know, in communication courses, students are given the chance and the opportunity in the space to communicate and to speak about issues in general and also to practice talking English in class, to be able to, you know, just like to engage and to participate. And to think aloud and so the communication courses for me were actually more successful than teaching literature students. (C, Personal conversation)

Note here that C also speaks about the relevance of “issues in general,” as did B. He also describes the inseparability of teaching communication and literature through the language of exposure:

Students are non native speakers of English. Some people think we should not teach literature to students. The only work that should be taught is skills and students should only be able to speak and to be able to write some decent writing. But that is not good enough, because they should be exposed literary texts and to be able to understand that and to be able to reflect on, you know, to be able to be critical and evaluative and to try to connect with the text and see if this is this, and the relevance in one way or another between a personal experience a student has had with the texts and songs. (C, Personal conversation)

B's and C's approaches are not a decontextualized teaching, but a radically immanent contextualization of literature inherited from colonialism. This philosophy of teaching was referred back more than once to the Palestinian teacher, scholar, and poet Khalil Sakakhini for whom “all learning occurs in context,” and rather than “giving rules for teaching Arabic grammar, present[ed] examples and ask[ed] the students to extract the methods and principles and apply them to other new problems” (Alshwaikh 67). The contamination of interests to which they speak is an apt place to begin planning for anticolonial collaboration with Palestinian teachers because it challenges us to ask what we have taken as the given distinction between the relevant contexts for teaching British literature. B and C's pedagogy provokes a thinking about the general interest of an anticolonial pedagogy that must get beyond national borders and their reinforcement through strict periodization, both of which militate against the interests that we might share with our Palestinian colleagues who are teaching the same texts as we do.

Beyond the Classroom and the Nation

A question worth continuing to ask is why the refrain of general interests appear in classrooms that themselves cannot be separated from colonial conditions and how the cultivation of such interests through communication is, or is not, bound up with struggles against colonial ways of knowing in our classrooms. Such questions will have to be asked directly in conversation with teachers in Palestine and through conversations cultivated through “the point” of Palestinian liberation from the occupation in all of its forms.

Some of the conversations that I had with instructors pointed in this direction through their own interests in texts from the Romantic and Victorian periods. For A, this makes Samuel Taylor Coleridge's “Kubla Khan” (1816) into more than an Orientalizing text, because of the centrality of imagination and power to it:

I also tell them that it's not all about colonialism, because there is you know, the other, because there are other things in the poem that are very rich, and that can be emphasized like the power of human imagination that has to do with colonialism in itself, but actually the power of our imagination, and how this power made [Coleridge] capable of building a palace in the in the air as we say. And then it was destroyed in a moment because he lost this connection to imagination and to nature. I connect it to Romantic philosophy because they believed in the power of imagination, and the inspiration of nature. So once you lose this connection to your imagination, then you can't be creative anymore. (A, Personal conversation)

A emphasizes both the power and fragility of the imagination, of its capacity to create “a palace” and the ease with which that power disappears in an instance. It is hard not to be drawn to the looming threat of the loss of creativity in this context, especially considered in relation to the destruction of Palestinian homes, archives, libraries, mosques, and farms that began with what Nur Masalha describes as “the hunt for ancient manuscripts, rare books, and associated artifacts [that] took place in the nineteenth century at the height of . . . European and Russian political and ecclesiastical penetration of the Holy Land” (283).

It would be all too easy to read a longing for national identity as determined by a Romantic ideology of sovereignty, borders, and self-possession into A's interest in the cultural and architectural power of the imagination. Yet everyone whom I had conversed with insisted on the historical importance of co-existence to Palestinian identity and that what is at the center of Palestinian demands for freedom is the end of Israeli sovereign power over their lives – and deaths – as well as the restoration of lands that had been part of Palestinian collective ownership for centuries prior to 1948. As D told me:

We have similar things between us and the Israelis. At the same time we have to be two-sided. Some brave literature, some brave writers say we can live with them. At the same time, we can't say directly that we can really live with them. This is occupation. If I want to go to Nablus I have to go through checkpoints. I cannot live comfortably. Really, we need our own freedom. We need to think like other people. We need at the same time, we need brave writers. (D, Personal conversation)

A described the same need for such writers in the context of combatting the patriarchal nature of Palestinian society under the conditions of, and in reaction to, the present occupation. This is where she described the relevance of Victorian literature to students' lives:

They connect to Victorian literature, particularly when we talk about women and their position. That's interesting. We talked about how the society was patriarchal and there were voices that reject this patriarchy, and they can connect to that. We have this suffering. The voices of women are silenced. So, when we talk about feminism, when we talk about gender issues, they feel that, yeah, they listen. Yeah, it makes sense. Because this is their suffering. And most of my students are female students actually. Like if I have a section of 35 students, 30 are female students and only five, or sometimes less, are male. (A, Personal conversation)

Survival and Knowledge

Whereas A told me that it was far more difficult to get students to connect to Romantic literature (especially poetry, because of its emphasis on nature and solitude), C proposed a direct and significant relationship between Romanticism, of both British and American varieties and Palestinian literature. According to what he called his own “self-analysis” of poetry, Romanticism was a huge movement in Arabic poetry more generally:

It's, actually, it's, an amazing influence, because it was not only social, but it was rather political because, you know, like Lebanese writers and Syrian writers and Palestinian writers were forced to leave Palestine at some stage in their lives, and then settled in the United States. Like, you know, like first generation immigrants, they had to write about nostalgia and love, politics and exile, and all these experiences, they had in the Middle East and they did that in poetry and tried to see the, you know, the, I would say the thread that ties politics together when it comes to, like, politics. And English romanticism, British romanticism in American romanticism, we have some similarities, definitely some influence going back. And the social economic context, actually, that writers have tried to reflect and the practice of dispossession and exile. (C, Personal conversation)

E also described the connection that she feels to a particular strain of Romanticism. She began with a citation from Lord Byron's poem, “Darkness” (1816):

“I had a dream, which was not all a dream / The bright sun was extinguish'd.” This line sets an unsure tone of darkness, of romantic darkness. Byron talked about the end of the world to the reader, the fallout that comes from that, and the cold and gloomy world which is full of fog. He gives people a sense of despair.

Dark romanticism is immensely about guilt, about sin, about suffering, so it does, or it touches our feelings and has this aspect of suffering, the deep side or the dark side of our life. Which I think not all works of literature do. And when talking about dark romanticism, it talks about something you have felt but that will not be noticed according to reason, that we don't have the language to talk about. So, dark romanticism may represent this feeling without words and this is the way we are maybe dealing with our situation here in Palestine. It deals with this suffering, this dark world which is Palestine, which is gloomy, which we cannot know when we will end this catastrophe. So there is no answer in the future, everything is dark, we don't have a happy, lovely, happy life. As we said, we don't have this glowing future, this glowing present.

So we have to look at the dark side, like other people look at the end. When [dark romanticism] deals with these aspects, when it deals with suffering, with sin, that the occupation does to us . . . it also deals with solitude. All of the writers here need to live in isolation so they can write about this situation, to collect or gather ideas in order to show people the immense pain, the immense suffering that Palestinian's have.

It talks about the importance of imagination, when referring to nature and human nature and the dark nature. Also in talking about this is to be alone, this is solitude to be alone, yes, because we are alone, as Palestinians we don't have someone to look to, to look at our issues and say we are with you, we are supporting you, we are siding with you. So it is to be alone, it is solitude. So, we don't have this bright side of life. And this is why I am very concerned with the dark and gloomy. (E, Personal conversation)

E introduced me to her extended family with immense generosity, sharing food, coffee, and her home whenever she could, and even arranged for her brother to drive me over three hours to where she was. She arrangedfor conversations with other teachers and for a visit to a school for students with learning disabilities. Her overwhelming generosity was paired at each point with a reminder of where we were, from the bullets still lodged in her brother's body to her mother-in-law's statement that she does not know a time when she was hopeful for Palestinians.

I was always reminded of the immanence of colonialism in every conversation that I had. This ongoingness begins in the periods we study, of which Ra'ad says “it is possible to view the 'rediscovery' of Palestine in the nineteenth century as 'Israeli prehistory'” (79). What might our relation to the pasts that we study look like when considered from A's perspective, in which colonialism is the traumatic present?

And when we talk about colonialism and postcolonialism, it's a very wide thing. We're not only thinking about one case of postcolonialism, because here in Palestine, it's very different. And it's not even “post” because the occupation is still here. So we have to think about it in a different way.

I write about trauma. And when I was reading about trauma it's all about the idea that it's a psychological injury, a shock that happens in the past. When I talk about Palestinian trauma, I thought that maybe it's different in this case, because the traumatic moment is repeated, like every day, we have like, traumas every day.It's not only about the Nakba, the one collective event, but it's also the trauma that happens every day because of occupation. It is ongoing and to think about post colonialism, it's the same because we're still colonized. Yeah. Yeah. So maybe, maybe, maybe everything can be seen differently.

We think we are civilized and we live in a civilized world that actually apologizes for colonialism. So now it's like a new page. But, actually, it's not because we still have these ideas of superiority. Yes. Because we still have wars and occupation.(A, Personal conversation)

At the time of editing these conversations and writing this essay, one of the universities that I visited has been closed at least twice due to invasions by the Israeli Defense Forces, and at least one professor I spoke with was facing immediate physical danger from Zionist settler attacks when she was able to travel to campus and teach. In this context of constant invasion, the opening out to what sustains interest for students outside of the university works as a way to refuse the reproduction of the colonial separation between aesthetics and material life. Moreover, it opens up the question for us about the relationship between survival and knowledge as an everyday one, and how that question gets lost when we are too committed to teaching context in such a way that it remains locked in the past.

Discussion Questions

- What did you learn about contemporary life in Occupied Palestine that you did not know before? What questions or gaps in knowledge did these conversations bring up for you about that context

- What is your experience of reading conversations as primary texts rather than historical documents or literature? What role do you think conversations and conversations might play in changing our ideas about scholarship or academic writing?

- Read some of the conversations in relation to postcolonial theories about the center and periphery. Discuss your thoughts in class.

- Consider how the context of Occupied Palestine as described in this essay affects pedagogy and classroom interactions. How do teachers respond in their classrooms and to their students in that context? Why do you think they respond in the ways they do?

- If you have spent time reading about and discussing Edward Said's notion of Orientalism, consider the extent to which that process continues to apply to dominant narratives of Palestine in U.S. culture. How do the experiences of Palestinian teachers speak back to the othering that Orientalism creates?

Works Cited

“Introduction: Occupied Hebron/Al-Khalil.” Mapping the Apartheid. February, 2016.

A. Personal Conversation. July 2022.

Alshwaikh, Jehad. “History of Education in Palestine: Time to Reconsider.” This Week in Palestine, Nov. 2014.

B. Personal Conversation. July 2022.

C. Personal Conversation. July 2022.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Kubla Khan.” Poetry Foundation.

D. Personal Conversation. July 2022.

E. Personal Conversation. July 2022.

“Five Palestinian Student Leaders at Birzeit University Seized by Israeli Occupation Forces.” Samidoun: Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network, 10 Jan. 2022.

Khalidi, Rashid. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. Columbia University Press, 1997.

Lord Byron (George Gordon). “Darkness.” Poetry Foundation.

Masalha, Nur. Palestine Across Millennia: A History of Literacy, Learning and Educational Revolutions. I.B Tauris, 2022.

Rafeef, Ziadah. We Teach Life. YouTube, 2011.

Said, Edward. The World, The Text, and the Critic. Harvard University Press, 1983.

Recommended Reading

Allen, Lori. “What's in a Link?: Transnational Solidarities across Palestine and Their Intersectional Possibilities.” South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 117, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 112–33.

Salih, Ruba, and Sophie Richter-Devroe. “Palestine beyond National Frames: Emerging Politics, Cultures, and Claims.” South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 117, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 1–20.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos, Continuum Books, 2005.

Lorde, Audre. “The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House.” 1987. Sister Outside: Essays and Speeches, Crossings Press, 2004, pp. 110–14.

Shehadeh, Raja. Palestinian Walks: Forays into a Vanishing Landscape. Scribner, 2007.

---. A Rift in Time: Travels with My Ottoman Uncle. OR Books, 2011.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “How the Heritage of Postcolonial Studies Thinks Colonialism Today.” Janus Unbound: Journal of Critical Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, Fall 2021, pp. 19–29.

Who Is Khalil Sakakini? Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center. October, 2021

Developer Biographies

Mohammad Sakhnini is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of English at Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi. He works in the fields of eighteenth-century British literature and culture and travel writing. His book, British Encounters with Syrian-Mesopotamian Overland Routes to India: Rethinking Enlightenment Improvement (1751-1795), has recently been published with Anthem Press (March 2023).

Lenora Hanson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at New York University. Their research focuses on dispossession and enclosure beginning in the Romantic period and as it continues into the present, with particular attention to the way that rhetorical language registers the destruction of non-capitalist forms of life. They recently edited a special issue of Studies in Romanticism entitled "Palestine: Romanticisms Contemporary" and published The Romantic Rhetoric of Accumulation (Stanford University Press, 2022).

Sarah Copsey Alsader is completing her PhD at the University of Kent on Discourses of Islam in British Romantic Poetry. She has research interests across literature, philosophy, religion and psychology, subjects which are pulled together through questions about metaphysical structures of feeling. She is especially concerned with how such structures of feeling shape and interpellate individuals, are written into and elided in narrative, and construct the world in which we live.

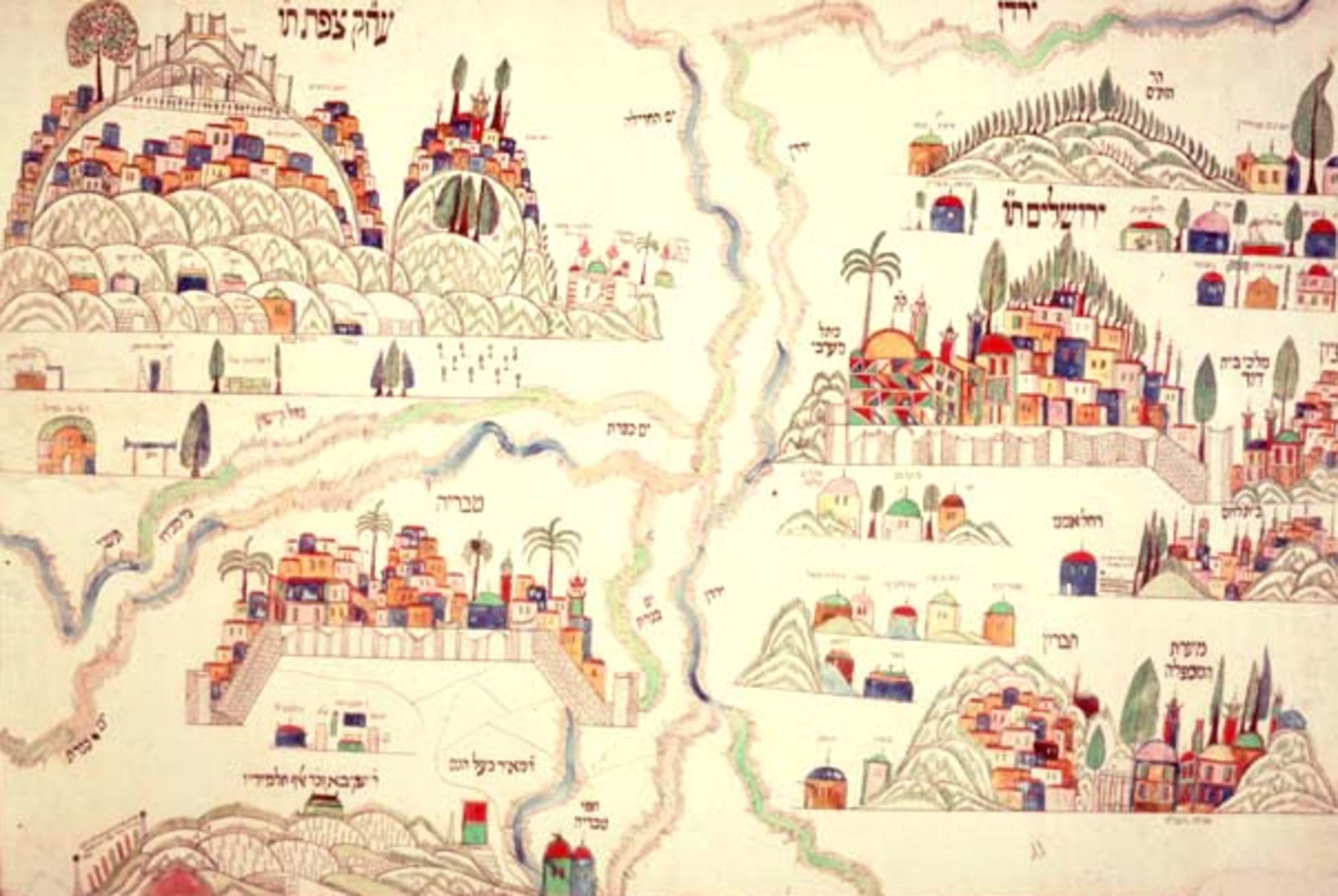

Tile/Header Image Caption

Once Known Artist. Holy Cities Plaque. 19th century. Hebraic Collections of the Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Page/Lesson Plan Citation (MLA)

Lenora Hanson, Sarah Copsey Alsader, Mohammad Sakhnini, dev. “Teaching Romanticism and Victorianism in Palestine.” Ryan D. Fong, les. plan clust. dev.; Cherrie Kwok, les. plan guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2023, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/lesson_plans/palestine_teaching_romanticism_victorianism.html.