Palestine in Victorian Travels and Travel Writings

Lesson Plan Production Details

Developers: Mohammad Sakhnini Contact, Sarah Copsey Alsader Contact, Lenora Hanson Contact

Lesson Plan Cluster Developer: Ryan D. Fong Contact

Lesson Plan Guide: Cherrie Kwok Contact

Webpage Developer: Ava K. Bindas

Cluster Title: Palestine in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Publication Date: 2023

Overview

This lesson plan invites students and teachers to consider how British travelers and travel writers found in their excursions in Palestine an opportunity to re-write the country and its populations as primitive and in need of European redemptive and civilizing power. That is, they did not exclusively operate within a discursive network of citations and interpretations long established in European writings about the Holy Land. This lesson plan also considers how these encounters with Palestinian communities and landscapes allowed British travelers to negotiate and redefine their affinity to their own nation and culture.

Many scholars of nineteenth-century European writings about the Middle East have reinforced the notion that British knowledge of the region can only be understood in the context of British imperial interests in the Arab-Ottoman world in the period following the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte (1799-1801).

For instance, Ilan Pappe, an eminent scholar of Palestinian history and culture, observed that “[m]ore than 3000 books and travelogs on Palestine were written by Europeans throughout the nineteenth century, all painting a picture of a primitive Palestine waiting to be redeemed by Europeans” (34).

To argue that most nineteenth-century Britons who went to the Holy Land were not keen on providing vivid recollections and descriptions of Palestinian lives is perhaps true, but the idea that all travel accounts showed prejudices towards, and projected British power over, the natives characteristic of what Lorenzo Kamel calls “Biblical Orientalism” and “cultural imperialism,” or that “all” Europeans who visited Palestine were, in the words of Pappe, “colonizers, Christian missionaries and Zionist settlers” is an overstatement (1; 32).

Indeed, Gudrun Krämer has warned of the anachronism of seeing all European travelers in the region as racist settlers and colonizers: “[nineteenth-century European] travel literature” she wrote, “is by no means as uniform as some of the critics of Orientalism describe it” (87).

A central learning objective of this lesson plan, then, is to invite students to consider how writing about, or visual representations of, Palestine equipped the British writer and artist with reflective opportunities, enabling her to confirm and also rethink the regime of science and progress, notions of patriarchy, and religious uniformity which dominated what John Stuart Mill called “The Spirit of the Age” in Victorian Britain (228).

Central Learning Questions

- How did the encounter with Palestinian locals allow European travelers to confirm or rethink some romantic associations in Europe which idealized the Holy Land?

- How did the rising British power in the Middle East or the growing European leverage over the Ottoman Empire throughout the nineteenth century shape representations of Palestinians in British travel writing about the Holy Land?

- Given that the harsh conditions of traveling in the Holy Land required that Europeans interact with locals who facilitated their movement across the region, how does such an encounter help to consolidate or disrupt European negative images of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish inhabitants of the Holy Land?

Suggested Materials and Discussion Questions

Below are suggested primary texts and images that might help students analyze the dynamics of Palestinian landscapes and culture.

The following texts and visual material are not meant to be representative of all British encounters with Palestine. Yet they can be read and viewed as examples that reflect the diversity of attitudes and approaches in British writings and art about Palestinian people and the landscape of Palestine. These materials invite students to explore how the idea of traveling and writing about Palestine represented a liberating experience for many Britons concerned about the radical changes in their own culture.

Primary Textual Materials

Clarke, Edward Daniel. Travels in Various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa (Part the Second). London: T, Cadell and W. Davies, 1810.

Clarke visited Palestine in the summer of 1801, less than two years after the British Navy (in cooperation with the Ottomans) drove Napoleon Bonaparte off the coast of Egypt and Palestine.

In his travel narrative about Palestinian cities, Clarke, who accompanied Captain Culverhouse on his mission to the Ottoman governor of Acre at the time, Ahmad Pasha Al-Jazzar, was mostly dismissive of what he saw as Christian superstitious traditions in the Holy Land. He critiqued the institution of the Catholic Church and considered any Christian (Oriental or European) who visits Palestine for purposes of performing the pilgrimage as “unable to discriminate between monkish mummery and simple truth” (432).

With the Bible in hand, Clarke found it impossible to believe what the local and Catholic traditions mention about the Holy Land, recalling that these traditions are nothing but superstitions and do not reflect what the Bible mentions about the topography and landscape of the region. To that end, his Palestinian journey was a way for Clarke, who was appointed professor of mineralogy at Cambridge after he returned to England in 1803, to critique Christian pietism represented in the worship of shrines and ruins instead of using reason to interpret the Bible.

Clarke found in writing about his experience in Palestine an opportunity to reflect on how religious enthusiasm and worship of relics lead to sectarian and religious wars, such as those of the Crusaders (of whom he was a critic).

The students who read Clarke's book might discuss the extent to which travels in Palestine allowed Britons to contribute to the debate in Britain and Germany at the time about the extent to which the Bible is a historical document, rather than a religious book valid for all people and at all times. Students can read Clarke's chapters about Palestine while studying the rise of Biblical criticism as a discipline in which travel writings about the Holy Land constituted an important component.

Possible Discussion Questions

- Why was the tension between religion and science in the pre-Darwinian period in Britain channeled into the field of travel writing about the Holy Land?

- How did Clarke's religious convictions and scientific career shape his views of the Holy Land and its different populations? Could faith be reinforced or undermined by new discoveries in archaeology, geography, and ethnography?

- To what extent was Clarke's journey in the Holy Land meant to deconstruct the romance of the Crusades, which was gaining momentum in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century with the publication in 1781 of Thomas Warton's The History of English Poetry, in 1794 of Thomas Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, and in 1805 of George Ellis's Specimens of Early English Metrical Romances?

Silk Buckingham, James. Travels in Palestine Through the Countries of Bashan and Gilead East of the River Jordan. London: Longman, Hurst and Rees, 1821.

Buckingham was the first writer in nineteenth-century Britain to use a travel narrative about Palestine as a medium to develop and express liberal, anti-colonial attitudes at a time when Britain's imperial stock in the Middle East was on the rise.

While in Palestine, Buckingham uncovered evidence that confirmed and justified his liberal views. He exposed the hypocrisy of missionary activities and undermined the rising calls in Britain for restoring the Jews. “That which myself witnessed confirmed to me,” he lamented, “all that I had heard and seen of the vile appropriation of religion here to the worst purposes” (252).

Buckingham did not call for possessing the land and reconstituting it anew; nor did he see it, as his countryman the Earl of Shaftesbury did, as an empty land needing the restoration of its original Jewish possessions.

Students could discuss how Buckingham's attitude towards Palestine was not only tied to Britain's rising commercial and imperial interests in the Middle East but also an illustration of rising political ideals during the period which critiqued British and European imperial and missionary activities in Palestine. Students can also read Buckingham's book in the context of an intersection in nineteenth-century Britain between liberal values and empire.

Possible Discussion Questions

- To what extent did the rising critique in Britain of the established church and theology shape Buckingham's views of religious rituals that he witnessed in Palestine, including those by European pilgrims?

- How does Buckingham's critique of British rule in India inform his critique of European missionary activities in Palestine?

- To what extent did Buckingham use his experience of traveling and socializing with different people in the Middle East as a prop to critique British and European prejudices against Islam and Arabs? To answer this question, students might also read selected chapters from other travel books written by Buckingham about different regions of the Middle East which he visited (such as his 1827 Travels in Mesopotamia and his 1829 Travels in Assyria, Media and Persia).

Richardson, Robert. Travels Along the Mediterranean and Parts Adjacent in Company with the Earl of Belmore. London: T. Cadell, 1822

Whereas Buckingham's walk in Jerusalem always led him to doubt the relevance of the Jerusalem of the Bible to the modern city, Robert Richardson's walks led him to strengthen his belief in the truth of the Bible and Biblical prophecies.

Robert Richardson was a Scottish physician with deep religious convictions. He was born in Stirling in 1779. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and graduated in 1807. After graduation, he practiced in Dumfries for a few years before he was able to use his medical skills for the purposes of improving his financial and social status. To that end, he worked as a traveling physician to Charles John Gardiner, second viscount Mountjoy.

In 1816, he joined Somerset Lowry Corry, known as the second earl of Belmore, and Corry's wife on a two-year journey in Europe, Egypt, and Palestine. While residing in Palestine, Richardson used his medical skills to develop friendships with local Palestinians, mainly the members of the elite, which allowed him to access religious sites in the city that few Britons had previously seen.

Richardson examined the famous Muslim site, Al-Aqsa Mosque, which many Britons during the period wished to see, but were unable or not allowed to enter its premises. The experience of strolling on the site and witnessing Islamic rituals reminded him of the ancient Jewish devotion he learned about from reading the Bible. While doing so, Richardson did not critique Islamic worshippers - a detail that encourages the reader to discuss the extent to which Richardson, like Buckingham before him, saw Jerusalem as a multi-faith center in which all monotheistic religions had valid claims.

Students could examine Richardson's views in the context of the rising debate during the period about religious uniformity and dissent (such as the debate in the 1820s around repealing The Test and Corporation Acts).

Moreover, students could discuss Richardson's attitude to the Palestinian landscape: for Richardson, as his book shows, freedom from the tyranny of the mind can be reached in the act of strolling in spaces untouched by modern schemes of improvements, among ruins illustrating the futility of material progress. Richardson's sentimental effusion equated strengthening one's faith with the idea of walking in ruined and barren sites, which recalls the fascination during the period with picturesque and sublime landscapes.

Students could also explore how representations of the Palestinian landscape helped travelers to pass political messages, one of which was a critique of industrialization and urbanization. Richardson's position was a political critique of the enchantment in Britain with excessive materialist culture, a position that he might have learned from the Romantic poets of his generation such as Lord Byron, who spoke highly of Richardson's Travels. Richardson, Byron recalled, “is just the sort of man I should like to have with me in for Greece-clever, both as a man and a physician” (512).

Possible Discussion Questions

- How does the Bible as a frame of reference shape how Richardson represents Palestinian people (living Biblical figures) and landscapes?

- To what extent do Richardson's encounters with local Palestinians allow us to deconstruct the dominant view in Western scholarship that all European writings about the Middle East constituted clear expressions of Western hegemony over the region and its population?

- How are British and European aesthetic discourses reflected in European representations of Palestinian landscape?

Martineau, Harriet. Eastern Life: Present and Past. 3 vols. London: Edward Moxon, 1884.

This multivolume book describes the author's journey in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, which the Christian and European mind has continually associated with ancient civilizations and religions. In her travel accounts about these lands, Martineau, whose writings on political economy and morals were informed by contemporary theories of evolution, aimed to show how contemporary religious practices (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) are derived from ancient pagan practices, religions, and traditions.

To that end, her critique of what many Britons during the period saw as the uniqueness of Christianity angered so many that Britain's leading publisher at the time, John Murray, refused to publish her book. Students, while reading the third volume of her work (mainly the chapters on her excursions in Jerusalem and its surroundings), are encouraged to discuss to what extent Martineau, who was ill while traveling in the East, confirmed and rethought gender stereotypes about travel and writing at the time.

By insisting on traversing roads previously untrodden by male travelers and by socializing with and observing Palestinians from different social and religious backgrounds, Martineau pushed the boundaries of travel and travel writings at the time by showing her readers how a female traveler can offer them more nuanced views about local cultures that none of the male travelers previously did.

To that end, Martineau, while confirming the philosophical positions of the Romantics at the time (Johann Gottfried Herder's writings about the evolution of society are useful here) believed that a Western traveler needed to understand how the local circumstances of people shape the formation of different cultural practices and value systems, and that these practices and systems are not the same in all countries and cultures.

If anything, Martineau was the opposite of the Enlightenment traveler who believed that European values and practices were the norms by which non-European cultures should be assessed. By constantly critiquing religious practices (particularly those related to polygamy and restricting women's choices) of all faiths that she encountered in Palestine, Martineau complicates the commonplace view at the time that female writers are meant to publish books encouraging piety, domesticity and conformity.

Possible Discussion Questions

- How did the rise of dissenting thought in Britain that critiqued organized religion shape Martineau's views of the religious communities she encountered in Palestine?

- To what extent did Martineau's economic thought, which is itself shaped by Enlightenment discourses about political economy, influence her views of the primitiveness of Palestinian society?

- How did prevalent notions of patriarchy and social hierarchy in Britain shape Martineu's view of Palestinian society and culture?

Ashworth, Jonathan. Walks in Canaan. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co, 1869.

Ashworth's narrative was mainly aimed to educate the lower and laboring classes in the north of England about the value of discipline, piety, and self-improvement. Ashworth's book was first published in Manchester by the House of Tubbs and Brook, a publisher specialized in commissioning and selling cheap self-help books, educational fiction, and religious tracts in order to diffuse the ethics of discipline among working classes.

Ashworth's Walks in Canaan was originally published in 1869 after a brief journey he undertook in the Holy Land in February 1868. It describes a few excursions Ashworth made across “the theatre of our Saviour's birth, labours, sufferings, death, crucifixion, and glorious resurrection” (38). The description of this theater, however, requires the traveler to be there on the spot: “The sorrows of our Saviour ... [are] read on the Mount of Olives with a force impossible to be understood in any other place” (38).

Ashworth did not seem to have departed radically from the dominant discourse in nineteenth-century British writings about the Holy Land: he saw Palestine as a land of piety, milk, and honey in the past but one of barren fields and superstitious people in the present, a land which reminded the metropolitan traveler of the vanity of human wishes. Indeed, this trope appeared in his Palestinian travel book, but it originally informed his Strange Tales (1871) and the great deal of lecturing that Ashworth did in the north of England before, and after, his excursions in the Holy Land.

Unlike many nineteenth-century travelers in Palestine, however, Ashworth, given his social background and interests in the causes of the poor in England, produced a narrative about his rambles among the poor in the city of Jerusalem, for whom he expressed sympathy and among whom he imagined himself as a savior, “a consistent man of peace,” which is how Friends' Review in 1870 described him (365).

Possible Discussion Questions

- To what extent were Ashworth's sympathies towards and commentary on the poor (Christian, Muslim, and Jews) in Palestine informed by discourses of self-help and self-improvement widely disseminated in nineteenth-century Britain?

- How did the comparable economic and social situation of the poor in Palestine and British working classes depicted in Ashworth's narrative produce affinities which complicate the polarities between East and West, Islam and Christianity, and Britain and the Middle East, that dominate the scholarship of European writings about the East?

Primary Visual Materials: Orientalism and Romanticism

This plan recommends analyzing the following images alongside famous paintings of the nineteenth century such as those by John Constable (for example, see Weymouth Bay [1824], a painting of a landscape) and Edgar Degas (for example, see Women Ironing [1875], a painting representing urban and working classes). Among the many paintings and etchings which represented Palestinian landscapes and people, two of the primary sources that were listed above are also particularly relevant for this section of the lesson plan: Richardson's Travels Along the Mediterranean and Ashworth's Walks in Canaan.

Seddon, Thomas. Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel. 1854-55.

According to the Tate Gallery, Seddon and his friend, Holman Hunt, went to the Holy Land in 1854, “to bring greater authenticity, spiritual and topographical” to their paintings which primarily touched on religious topics, concerns, sensibilities, and memories. The painting above shows “the Mount of Olives and the Garden of Gethsemane, the site of Christ's anguish before the Crucifixion.”

“Unlike John Martin's apocalyptic visions, displayed nearby,” the Tate Gallery adds, “Seddon represents the site in painstaking, sun-lit detail, paralleling the art critic John Ruskin's remarks that 'in following the steps of nature, artists were tracing the finger of God.'”

Students can pair the paintings above with Simon Coleman's critical essay on "the sublime and meticulous" in which the dilemma of mapping the Holy Land into the religious and scientific sensibilities of the Victorian age resulted in the emergence of complex artistic articulations. British writers and artists, despite discrediting the traditions of pilgrimage to the Holy Land, insisted on visiting and seeing the Holy Land.

The anthropological and skeptical sensibilities of the period required the artist and writer to visit Palestine and report about it objectively. However, as Coleman has observed, “[c]onveying relevant 'truths' involved a negotiation between scientific demands for exact description on the one hand, and theological requirements to present powerful religious experiences that would engage the reader on the other'' (276). At stake here is the idea of “distance between the observer and observed” (277).

Students can discuss the extent to which Seddon and other painters and travel writers who represented Palestinian landscapes visually or textually mystified the social and political reality of the land in which they traveled.

Harry Fenn, A Grocer's Shop in Jerusalem. 1880.

Harry Fenn's plate above appeared in Charles Wilson's Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt (1881), a book that lavishly illustrates famous Biblical and archaeological sites in the Holy Land. Wilson prepared his Picturesque Palestine for the English press after he returned from the Holy Land where he worked for the Palestine Exploration Fund as a surveyor, geographer, and archaeologist for a few years. In this illustration of the streets of Jerusalem, Finn drew on the existential artistic traditions in Britain, such as those by George Fredrick Watts, Albert Daniel Rutherstone, and Philip de Loutherbourg, who used arts for purposes of representing the social and moral concerns of the public at the time-concerns about urbanization, industrialization, and poverty in radically changing Britain.

The concerns about poverty conveyed through the serious impressions of the poor female vendors in the image above can be paired with George Fredrick Watt's painting, The Song of the Shirt (1850), which represented the terrible circumstances in which British seamstresses lived and worked. Students could pair Finn's plate above with chapter five in Michelle Facos's An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art (2011), which analyzes the changes the art scene witnessed in Victorian Britain—one which reflected the social situations of the laboring classes.

Secondary Materials

Palestine in the Western Imperial Mind

Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua. The Rediscovery of the Holy Land in the Nineteenth Century. 1779. Wayne State University Press, 1979.

Coleman, Simon. “From the Sublime to the Meticulous: Art, Anthropology and Victorian Pilgrimage to Palestine.” History and Anthropology, vol. 13, no. 4, 2002, pp. 275-90.

Facos, Michelle. An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art. Routledge, 2011.

Kamel, Lorenzo. Imperial Perceptions of Palestine: British Influence and Power in Late Ottoman Times. I.B Tauris, 2015.

Kramer, Gudrun. The History of Palestine: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Founding of the State of Israel. Translated by Graham Harman and Gudrun Kramer, Princeton University Press, 2008.

Pappe, Ilan. The History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples. The University of Cambridge Press, 2006.

Palestine and Radical Changes in British Culture, Art and Literatures

Bar-Yosef, Eitan. The Holy Land in English Culture 1799-1917. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hess, Scott. William Wordsworth and the Ecology of Authorship: The Roots of Environmentalism in Nineteenth-Century Culture. The University of Virginia Press, 2012.

Masalha, Nur. The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory. Routledge, 2014.

Yoshikawa, Saeko. William Wordsworth and the Invention of Tourism, 1820-1900. Routledge, 2014.

Developer Biographies

Mohammad Sakhnini is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of English at Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi. He works in the fields of eighteenth-century British literature and culture and travel writing. His book, British Encounters with Syrian-Mesopotamian Overland Routes to India: Rethinking Enlightenment Improvement (1751-1795), has recently been published with Anthem Press (March 2023).

Lenora Hanson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at New York University. Their research focuses on dispossession and enclosure beginning in the Romantic period and as it continues into the present, with particular attention to the way that rhetorical language registers the destruction of non-capitalist forms of life. They recently edited a special issue of Studies in Romanticism entitled “Palestine: Romanticisms Contemporary” and published The Romantic Rhetoric of Accumulation (Stanford University Press, 2022).

Sarah Copsey Alsader is completing her PhD at the University of Kent on Discourses of Islam in British Romantic Poetry. She has research interests across literature, philosophy, religion and psychology, subjects which are pulled together through questions about metaphysical structures of feeling. She is especially concerned with how such structures of feeling shape and interpellate individuals, are written into and elided in narrative, and construct the world in which we live.

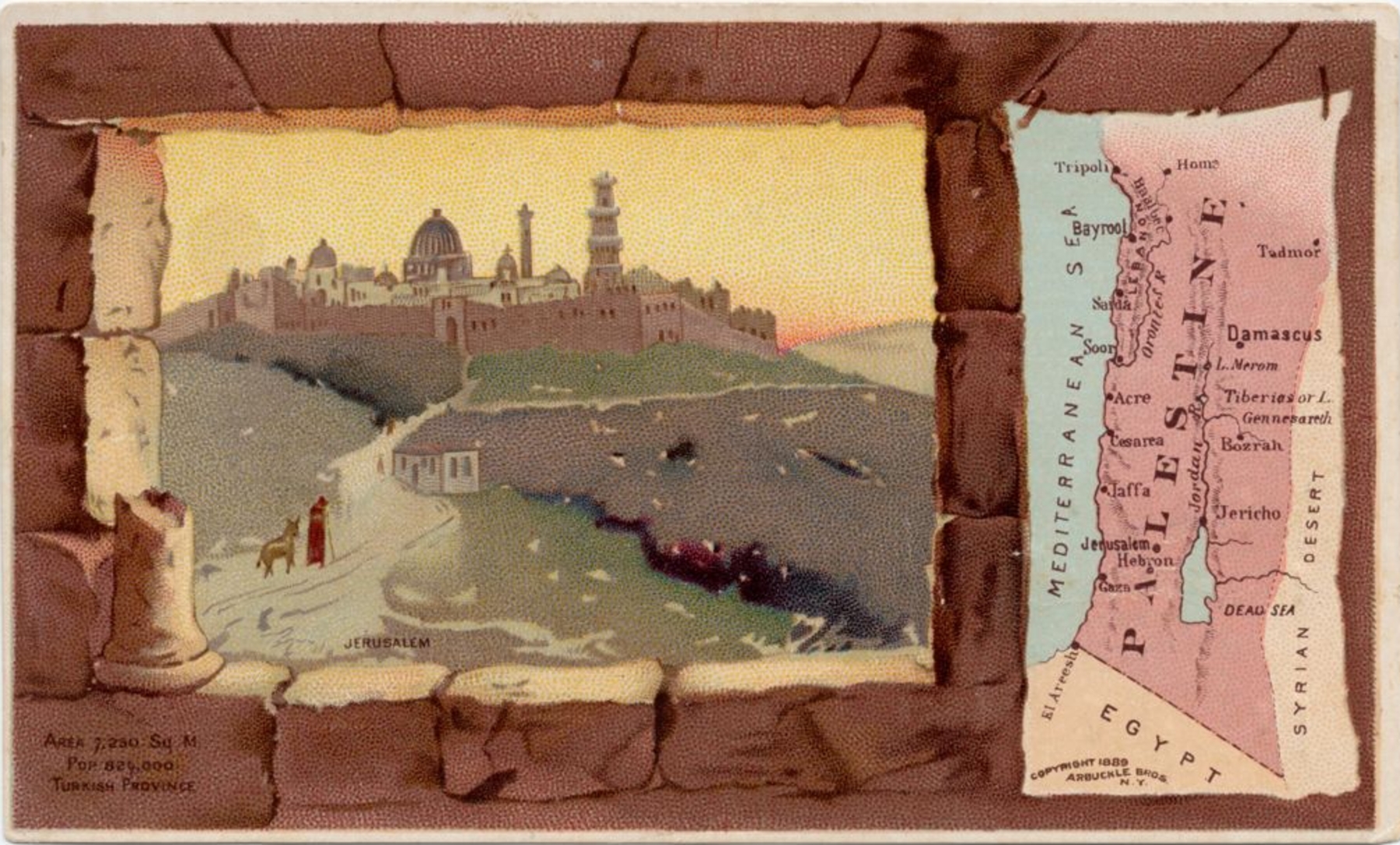

Tile/Header Image Caption

Arbuckle Bros., Palestine. 1889. New York Public Library Digital Collections, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division. Free to use without restriction.

Page/Lesson Plan Citation (MLA)

Mohammad Sakhnini, Sarah Copsey Alsader, Lenora Hanson, dev. “Palestine in Nineteenth-Century British Travels and Travel Writings.” Ryan D. Fong, les. plan clust. dev.; Cherrie Kwok, les. plan guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2023, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/lesson_plans/palestine_travel.html.