Capital L-Literature: Intro to Grad Studies

Syllabus Production Details

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

This syllabus represents my ongoing effort to reconsider the required “Introduction to Graduate Studies” course at my public M.A.-granting institution so that it serves our diverse student body, some of whom will go on to Ph.D. programs but many of whom will pursue teaching, administration, non-profit work, and industry positions. While mine is not thematically a “Victorian classroom,” my training in nineteenth-century British literature nevertheless shapes the syllabus I’m contributing to this cluster on “deconstructing the literary canon” by foregrounding the creation of literary studies as a historical political endeavor with ongoing relevance within and beyond academia.

My top priority in “Introduction to Graduate Studies” is to teach students how to reflect critically on the intellectual spaces they inhabit, to see how these spaces are created and policed, and to use theory for their own purposes rather than for mine. One of the most important functions of my course, then, is to help students recognize themselves as agents who actively shape the field. In order to build a community of scholars who can assert their voices, I bookend the course with an intellectual narrative assignment and a reflection letter, in which we each share something we learned and consider how we will build on that knowledge going forward. The “we” here is literal: I do these assignments alongside the students, and I think that is crucial for deconstructing at least some of the traditional classroom power dynamics without pretending we all have equal power.

The course theme, “Capital-L Literature,” represents an intentional effort to close “the gap between theory and practice,” as bell hooks advocates (63). I emphasize interrogating the political, historical, and social contexts of literary studies itself by introducing canonical theoretical approaches alongside scholarship that demands readers analyze the political situatedness of that theory. Students take a metatheoretical perspective of the field, asking what counts as “Literature” and exploring the history of which texts, approaches, and methods have held scholarly weight and which have been excluded (and, crucially, what effects inclusion and exclusion achieve).

Rather than “Victorian” or “British” or “nineteenth-century” as the determining rationale for the literature, I focus on the sonnet – a form poet Jericho Brown has said he is “completely in love with and oppressed by” (Williams). I chose the sonnet because it is one of the most continually produced poetic forms in English and because it is a bite-size example of “Capital-L Literature,” both inspiring and “oppress[ing]” writers today. By centering a form rather than a period or nationality, I can assemble writers who, like Brown, deliberately enter a literary conversation about Western tradition (and oppression). Alongside sonnets by William Shakespeare and William Wordsworth, we read innovations of the form, including Marilyn Nelson’s picture book A Wreath for Emmett Till (2005). Nelson’s book combines a traditional poetic form that students often regard as antiquated (sonnet redoublé) with the unexpected medium of an illustrated children’s book. Through it, we ask how historical narratives determine who typically warrants memorialization in literary studies and who gets left out or limited to specialist study.

This inquiry is practical as well as theoretical because one inevitable problem of the “Introduction to Graduate Studies” course is that it must do too much. So, students consider how institutional requirements, professional expectations, and my syllabus shape their impressions of “Literature” and the kinds of research projects they pursue. We do this deliberately in class in week 3, for example, when students practice looking for patterns among the poets I’ve assigned so far (in the first three weeks, these are, by design, all “canonical” writers). Students ask what arguments and value systems my choices imply through inclusion, exclusion, and arrangement.1

A learning outcome for this course, set by my department, is training students to “apply different theoretical and critical approaches to literature” (Chappell). Many programs, mine included, have traditionally oriented new scholars by underscoring the canonical authority of, say, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida – supplemented maybe by Judith Butler or Edward Said if there’s time. To be sure, these are important figures, but I don’t want this introductory course to establish literary studies as predominantly white and European or to reinscribe the same classist applications of theory that a figure like Marx would condemn. Instead, my syllabus depends more on Black feminist studies, postcolonialism, and critical race theory not because these theories are any less complex but because my students more readily see the relevance of this work to their lives. I find that centering these theories encourages students to recognize our classroom as part of the broader world and know that their experiences are relevant and valuable here.

Perhaps without meaning to, we often train graduate students, many of whom will simultaneously be instructors within our universities, to mimic received knowledge in order to prove their worth. Rather, I want to present theories as potential tools for understanding and intervening in lived experience. I format the reading schedule to encourage students to interact with it, showing them how they might engage each reading as preparation for shaping class discussion. Although I divide each week’s readings into “poetry” and “prose” for clarity, I avoid the designations of “primary” and “secondary” that I might use in other classes because here it is crucial to regard all texts as primary objects for analysis. After close reading poems, students scale up that methodology to produce a “metanarrative” in which they close read an existing canon of their choice, such as an anthology, a syllabus, or a curriculum.2 These readings and assignments often lead us back to theories like historicism and poststructuralism but with specific purpose, uniting theory with deliberate practice.

Beginning from a foundation of scholarly situatedness encourages students to learn with a sense of significance. I want to prepare them so that, once they have determined a plan for their own work, they will know where to start reading, motivated by their own interests and priorities to use theory in their scholarship, to engage it, rather than to see it as a boundary enforcing who’s in and who’s out – as “a mark of status,” as Lois Tyson puts it (1). I want my syllabus to suggest possibilities for disrupting the “path dependency” of how we train new scholars in the university (Levine 59). That means breaking any tacit equation of foundational theory with white European thinkers, as well as making visible institutional traditions, contextualizing them, and engaging them in discourse.3 This framing helps students know theoretical approaches as objects of analysis and application rather than as law.

As Caroline Levine argues in Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, our institutions “endure […] because participants actively reproduce their rules and practices” (58). If we do not constantly reproduce canonical white European literary studies in the university as the dominant (or only) narrative, perhaps other ways of knowing and seeking knowledge and even using canonical knowledge can develop. At the very least, to begin graduate work in literature by first recognizing literary studies as a historical construction will, I hope, encourage students to embrace their authority in this space and to use theory to serve their practices, whatever they might be.

- See syllabus note under “Week 3” for more information about how I do this and an alternate suggestion. Back to text

- In addition to Ronjaunee Chatterjee, Alicia M. Christoff, and Amy R. Wong’s “Undisciplining Victorian Studies,” I assign Nathan Hensley’s blog post, “The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 10th Edition: Volume E, The Victorian Age. Reader's comments,” to help students see what a metanarrative for a field might look like. Back to text

- Sometimes this means limiting our reading of a theory to broad strokes overviews, but so far I have found that students can master the learning outcomes of an introductory course just as well with these shorter introductions. For this, I like the Purdue OWL’s pages on “Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism”; the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which includes more detail; Rivkin and Ryan; and Tyson. I am grateful to Kendra R. Parker for the suggestion of Tyson’s anthology. Back to text

Works Cited

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 10 July 2020.

Lindsey N. Chappell, dev. “Capital L-Literature: Intro to Grad Studies.” Rachel Sagner Buurma, peer rev.; Sophia Hsu, syl. clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2022.

Hensley, Nathan K. “The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 10th Edition: Volume E, The Victorian Age. Reader’s Comments.” Nathan K. Hensley, 21 July 2020.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Levine, Caroline. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Purdue OWL. “Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism.” Purdue Online Writing Lab, 2021.

Rivkin, Julie, and Michael Ryan. Literary Theory: An Anthology. 2nd ed., Blackwell, 2004.

Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy. 2022.

Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006.

Williams, Candace. “Gutting the Sonnet: A Conversation with Jericho Brown.” The Rumpus, 2019.

Deconstructing the Literary Canon Series

This cluster of syllabi deconstructs the literary and literary critical canon upon which Victorian Studies has been built. Through frameworks from Critical Race Theory, Postcolonial Theory, Empire Studies, Critical Ethnic Studies, and Critical Pedagogy, these syllabi expose students to the political work of canon formation and disciplinary knowledge production. By treating what scholars usually define as secondary materials as primary texts, these courses not only orient students to Literary Studies and Victorian Literary Studies as academic fields but also engage students as agents who can shape these fields via discussions about curriculum, canonicity, and disciplinary norms.

Developer Biography

Lindsey N. Chappell is Assistant Professor of English at Georgia Southern University, where she teaches literature courses on time, empire, and extreme sports. She is currently working on a book called Temporal Forms: British Heritage Discourse and the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean. Her publications have appeared in Nineteenth-Century Contexts, Victorian Literature and Culture, ELH, SEL, Victorian Review, and Literature Interpretation Theory.

Tile/Header Image Captions

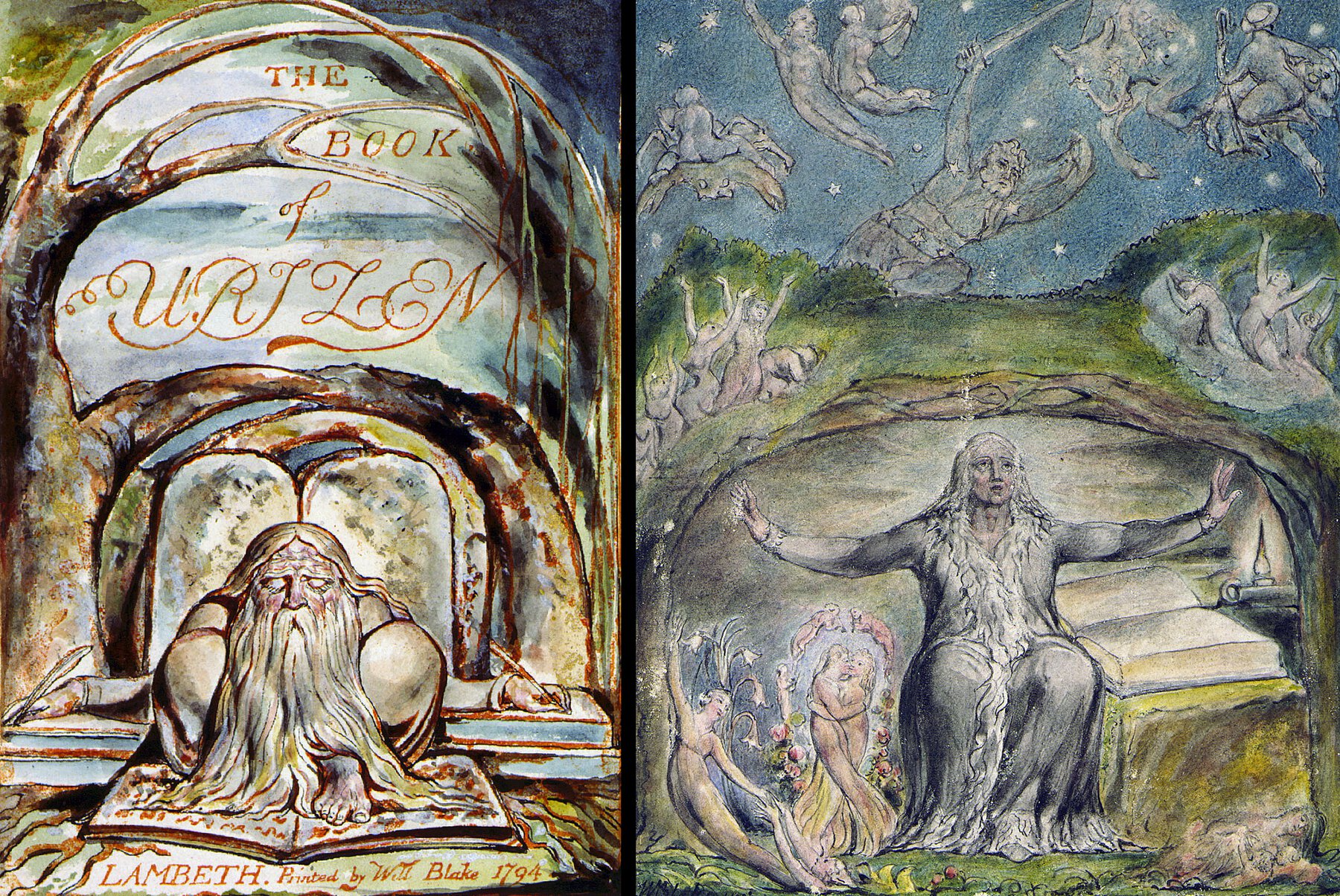

(Left) Blake, William. “The First Book of Urizen.” 1794 (composed); c.1818 (printed). The William Blake Archive, The Book of Urizen, Copy G, Object 1 (Bentley 1, Erdman 1, Keynes 1). Fair use.

(Right) Blake, William. “Milton in His Old Age.” c.1816-20 (composed). The William Blake Archive, Illustrations to Milton’s “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso,” Copy 1, Object 12 (Butlin 543.12). Fair use.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Lindsey N. Chappell, dev. “Capital L-Literature: Intro to Grad Studies.” Rachel Sagner Buurma, peer rev.; Sophia Hsu, syl. clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2022, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/capital-l_literature.html.