Hinduism and Imperial Interventions in Victorian Literature

Syllabus Production Details

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

Religion was vital to colonial and anticolonial discourse, serving as a tool for both British colonization and Indian nationalism in the nineteenth century. Prior to British colonization of the Indian subcontinent, Hinduism was an amorphous religion with many sects and multiple belief systems. During colonial rule, British perspectives cast Hinduism as a single, unified, monolithic religion and all Hindus as backwards and uncivilized. The British used religion to assert their essential difference from colonized people, otherizing Indians on the basis of their faith, and to justify their incursion on Indian sovereignty, framing colonization as a “civilizing mission” to rescue the “benighted pagan” (Pennington 24). But conservative and reformist Hindus alike resisted the British view of Hinduism and used religious identity to further the nationalist cause.

This lower-division undergraduate course, which I hope to teach in the future, analyzes Anglophone literature produced in and about nineteenth-century India to help students recognize the complex interrelations of colonialism, nationalism, anticolonialism, and religion. Focusing on the conjunction of religion and literature in nineteenth-century India, I aim to introduce students to three main ideas: 1) that Victorian literature goes beyond the literature produced in the British Isles, 2) that religion was significant to nineteenth-century Anglophone literature(s), and 3) that historical and cultural readings are important to nuanced literary analysis.

The readings in the course explore the impacts of British colonial rule and nationalist resistance on Hindu cultural and religious practices as well as their concomitant influence on Victorian literature. My syllabus emphasizes women writers because the British used what they perceived as Hindu women’s oppression to validate colonization in the nineteenth century. The condition of Hindu women, and especially “sati” (self-immolation of the Hindu widow on her husband’s funeral pyre), was the most commonly cited rationale for British colonization, which Gayatri Spivak has famously called “white men saving brown women from brown men” (93).

Women’s writings in and about British India, however, were not limited to the subject of sati, whether for or against the practice. Rather, in nineteenth-century India, women writers connected religion to a variety of topics and supported a broad range of stances, tackling such issues as Indian feminist nationalism, Christian conversion, moderate reformism, and British traditionalism. In addition to encouraging students to analyze religion critically, a goal of this course is to demonstrate the array of women, and notably women of color, writing in the nineteenth century. Another major goal is to introduce students to historicist reading of literary texts. Therefore, each unit includes secondary sources such as Partha Chatterjee's “The Nationalist Resolution of the Woman Question” to help students conduct a richly historicized critical analysis.

The first unit introduces students to the concepts of colonialism and orientalism and explains how the political agendas of colonizing forces stereotype and marginalize a specific religion and religious community. In Unit 1, students read about how the British used the Hindu practice of “sati” to justify colonial rule. Students engage with primary texts like Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone and Rudyard Kipling's “The Ballad of the Last Suttee” to examine how British colonizers stereotyped Hindus as misogynist and backwards and fetishized Hinduism as a mysterious and inscrutable religion.

Unit 2 explores how Hindus internalized the colonial otherization of Hinduism and also considers certain valid criticism of Hinduism by nineteenth-century Indian writers. On one hand, many Hindus saw Hinduism as oppressive and converted to Christianity. On the other hand, some Hindus called for reforming the religion itself to keep up with the progressive nationalist politics. In this unit, students read gendered critiques of Hinduism, such as Pandita Ramabai’s polemical text The High Caste Hindu Woman (1887) and conversion narratives like Krupabai Satthianadhan’s semi-autobiographical novel Saguna (1895). Reading about both the internalized otherization of Hinduism and the legitimate critiques of some of its practices offers students a thorough understanding of the complexities of religion in a colonized society.

The third unit focuses on how conversion, reform, and religious conflicts were also linked with nationalist movements in nineteenth-century India. Students read about women nationalist leaders like Sarojini Naidu and British perceptions of anticolonial movements, such as Flora Annie Steel’s novel The Hosts of the Lord (1900) that connects religious and political conflicts. Indian nationalist movements utilized religious sentiment to galvanize public opinion against the colonial government. Students learn how the perception of religion influenced the political trajectory of India’s independence movements.

The assignments and activities in this course allow students not only to read and analyze literature but also to connect their learning to the present day. We are living in a world that is becoming more and more polarized and intolerant. Right-wing, religious extremist movements are once again becoming mainstream across the globe. Taking a historical view of the connections between religion and colonialism helps students understand and respond to the rising threat of extremism. This course thus embodies Paulo Freire’s liberatory, humanist model of “problem-posing education” that helps “people develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves” (83). In this undergraduate course, students, who are the future citizens, voters, politicians, and activists, will hone their critical thinking skills as they explore and connect literature, history, and current events.

For example, in each unit, students participate in a debate that gives them the opportunity to discuss and reflect on the impact of colonialism on literary representation and the otherization of religious identities. Through this activity, students have the chance to connect the texts to current events such as xenophobic evangelical Christianity in the U.S. and violent right-wing Hindutva in India. In another project that I call “Colonial Legacies,” students further explore the modern-day impacts of nineteenth-century colonialism.

For this project, students watch the 1984 miniseries The Far Pavilions that depicts colonial India. The six-part series is orientalist and prejudiced, part of the “Raj nostalgia” of the Thatcher era that glorified British colonialism. In groups, students lead discussion on different episodes that correspond with each course unit, allowing them to see for themselves the lasting effects of colonization on representations of Hinduism on television. For the final project, students examine one to two texts and draw their own conclusions about the connection between colonialism and the “religious other”, which they share with their peers through multimedia presentations. All the assignments are structured for flexibility in terms of topics, word limit, submission deadlines in a way that is responsive to their needs to encourage students to take a deeper dive into the texts

From the reading selection to the assignment design, I have constructed this course to align with the anticolonial sentiments of the writers in my final unit. While the specific aim of the course is to encourage students to critically examine religion’s place in British colonialism, this aim is part of the broader movement in Victorian Studies to problematize the adjectives ‘British’ and ‘Victorian.’ Despite the recent developments in the field, there is an unfortunately enduring belief, among undergraduate students in particular, that “British” literature only means literature from the United Kingdom. By exploring the context of the British Empire and reading literature from colonial India, this course ultimately poses the question: What is “British” literature? There is no simple answer to the question, but this course encourages students to explore it further.

This course also demonstrates that “Victorian” is a plural term, and the Victorian world encompassed a large portion of the globe and a great variety of races, languages, and beliefs. As Sukanya Banerjee, Ryan D. Fong, and Helena Michie have argued, “the appellation ‘Victorian’ marks less a certain period of monarchical reign than it does a political, aesthetic, and sociocultural assemblage” (2). This syllabus thus follows in these and other scholars’ footsteps who have “widened” the terms “British” and “Victorian” by providing a range of perspectives in a non-hierarchical manner to explore Hinduism in the colonial era and its representation in Victorian literature. Hopefully, this syllabus will serve to “widen” Victorian Studies even more and encourage students to be excited about Victorian literature.

Works Cited

Banerjee, Sukanya, et al. “Introduction: Widening the Nineteenth Century.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 49, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1–26.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos, 30th Anniversary Edition, Continuum, 2000.

Pennington, Brian K. Was Hinduism Invented? Britons, Indians, and the Colonial Construction of Religion. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, edited by Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, Columbia University Press, 1994, pp. 66–110.

The Nineteenth-Century Religious Other Series

While religion remains a central topic in the field of Victorian Studies, scholars continue to prioritize Christian perspectives. This cluster of syllabi provides resources that expand engagement beyond Christianity, highlighting texts by and about those considered religious “others” in the nineteenth century. Through frameworks from Postcolonial and Religious Studies, the cluster decenters white Christian metropolitan Britishness by amplifying the voices of those who have been often overlooked due to racial and religious biases. At their best, religions cultivate attitudes of care, and in teasing out the multifaceted Victorian religious perspectives with which students may not be familiar, these syllabi seek to broaden religious tolerance, awareness, and appreciation.

Developer Biography

Sanjana Chowdhury is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of English at Texas Christian University, where she is working on her dissertation on British Empire foodways. She has published an entry on Hinduism in the Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women’s Writing (2022). Her research interests include Victorian literature, long-nineteenth-century foodways, political economy, and British Empire history.

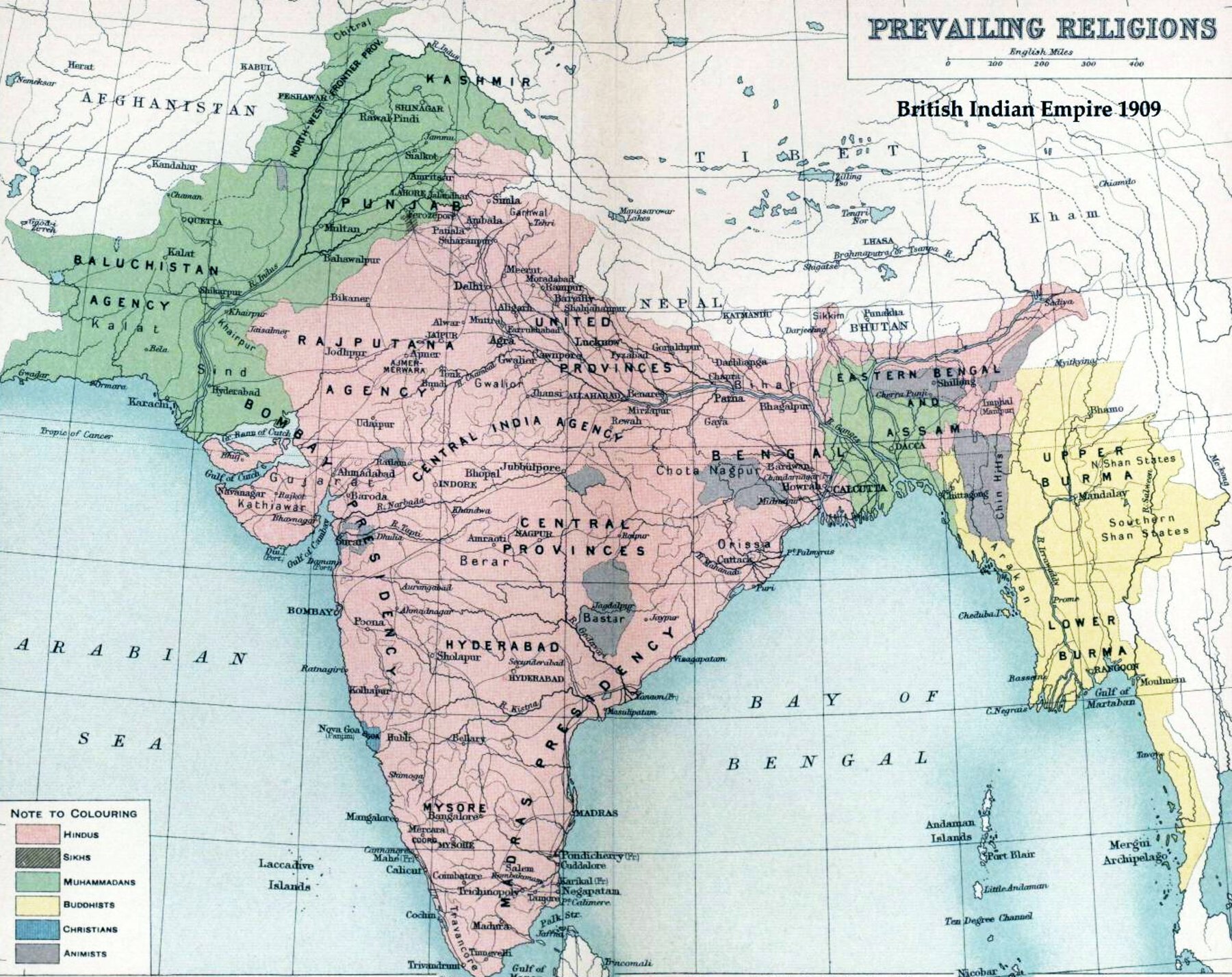

Tile/Header Image Caption

Bartholomew, John George. Prevaling Religions: British Empire. 1909. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Sanjana Chowdhury, dev. “Hinduism and Imperial Interventions in Victorian Literature.” Mark Knight, peer rev.; Dana Aicha Shaaban, syl. clust. dev.; Sophia Hsu, syl. guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2023, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/hinduism_imperial.html.