Race, Trans-Atlantic Slavery, and the Empire

Syllabus Production Details

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

This graduate course explores connections between British slavery and empire, and analyzes their racializing assemblages within a longer cultural history from the seventeenth century to today. It reads slavery and empire through a Black Studies framework, foregrounds writers of color, and presents slavery as foundational to Victorian literature. If, as Alexander Weheliye claims, Black Studies is an intellectual tradition that began in the eighteenth century (3), and, as Ronjaunee Chatterjee, Alicia Mireles Christoff, and Amy R. Wong state, “scholars of Victorian literature and culture are, in fact, scholars of Atlantic slavery” (370), prefacing the Victorian era with slavery helps us see Victorian literature as part of slavery’s afterlife.

British slavery, which wasn’t fully abolished until 1838, brought an influx of colonists to the Caribbean where sugar production boosted the British economy and fueled the Industrial Revolution that gave birth to the Victorian novel. The beginnings of settler-colonialism can be traced back to 1441, when the Portuguese arrived on the shores of Senegal and initiated the trans-Atlantic slave trade (King 18). And the rise of the Western novel was deeply engaged with slavery and empire, as seen in foundational texts such as Oroonoko and Robinson Crusoe. Taking seriously the Victorian era’s indebtedness to slavery deepens our conversations about both Victorian empire and the role of Victorian literature in the formation and solidification of racial categories.

This class enacts what Christina Sharpe has defined as “wake work”: we work toward “plotting, mapping, and collecting the archives of the everyday of Black immanent and imminent death” at the same time we “resist, rupture, and disrupt that immanence and imminence aesthetically and materially” (3). Although we read the history of enslavement from a majority Black point of view, I refuse to let Blackness be read only as enslavement, subjection, and reduction to flesh. Alongside our opening readings from Black Studies, we examine examples of early British travel narratives, philosophy, and scientific discourses to analyze how humanity was what Zakiyyah Iman Jackson would call “plasticized” within white accounts of colonialism and enslavement (3). Yet as a juxtaposition to these representations, we consider Weheliye’s desire to think “humanity creatively,” and “launch alternate ways of understanding our uneven planetary conditions and imagine the other worlds these might make possible” (11, 15).

While it’s perhaps more difficult to find these “other worlds” in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British literature, I ask students to try to “move beyond a critique of bestialization to generate new possibilities for rethinking ontology” (Jackson 1). One way I do this is to introduce Black writers beyond enslavement, not only through fronting our historical readings with contemporary Black scholars, but by showcasing early Black literary production beyond the slave narrative, as in week six, where we read poems by Phillis Wheatley alongside letters by Ignatius Sancho.

Further, in class discussions I ask students to look for what Katherine McKittrick and Tiffany Lethabo King call “Black livingness” and locate “representations of Black flutter, kinetics, and flight” that “inspire preliminary and early, or proto-, conceptions of Black fungibility” and “emerge as an anxious response to Black uncontainability and fugitivity” (McKittrick, qtd. in King 77; King 77). I frame this mode of reading as what Sharpe would call “taking care,” “Black annotation” and “aspiration”: “imagining and [...] keeping and putting breath black into the Black body in hostile weather” (20, 113). As another way of “taking care,” and at the request of my students after having taught a version of this course in Spring 2021, I’ve included a warning about texts that contain particularly intense depictions of white supremacist violence. Yet in class discussions I try to veer from focusing on these instances, looking instead for Black life, which leads to productive conversations about how to read. For the problem my students and I dealt with in this kind of reading, and spent time discussing, was how to be sure we were not “forgiving” white writers for their displays of violence by projecting onto older texts an agency, freedom, or fugitivity that wasn’t there.

Not only do I ask students to understand Blackness as an “object of study” (Weheliye 18) rather than as something natural, given, or biological, I refuse to let whiteness go unnamed and unrecognized. Reading for Black livingness and aspiration helps us analyze whiteness as white supremacy and locate white anxiety and destabilization. Framing the class with Black scholars emphasizes the whiteness of many of our primary texts and helps us analyze how they led to the “coherence” of whiteness as a racializing force. As King stresses, “There is so much work that could be done on whiteness and how its coherence requires parasitism in order to survive [...] There is this ongoing and enduring question of how does whiteness require Black death. Deal with that” (King, in King and Wilderson 57).

Therefore, we conceptualize race as an assemblage, and I structure my readings as such. For example, we read white writers in conversation with writers of color and consider each day’s reading as its own racializing assemblage. This goal is helped by reading literary works by contemporary Black writers. I was inspired by Saidiya Hartman’s call for critical fabulation: “laboring to paint as full a picture of the lives of the captives as possible [...] straining against the limits of the archive to write a cultural history of the captive, and, at the same time, enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration” (11). Through this I offer more Black perspectives to our historical contexts while showing how not to “give voice to the slave, but rather to imagine what cannot be verified” (12). To further help students understand the limits of the archive they analyze a digital archive/humanities project for one of their major assignments, using one of our theoretical sources to analyze how well the project decenters whiteness and opens space for Black voices and perspectives.

By centering Black studies scholarship and Black writers, I aim to displace the centrality of European scholarship and literature, privilege Black studies as something beyond a “minority discourse” (Weheliye 6-7), and show how the Western novel developed in tandem with British slavery. This allows us to think more critically about the whiteness of Victorian literature and undiscipline the exclusionary nature of Victorian Studies more generally. By making the Victorian literature classroom an antiracist space, my students can better see how contemporary notions of race cohered in the nineteenth century. And hopefully, my majority non-white students feel more invited into a time period that can feel alienating when they are, in fact, an important part of the conversation.

Works Cited

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Introduction: Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Victorian Studies, vol. 62, no. 3, Spring 2020, pp. 369–91.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe, vol. 12, no. 2, June 2008, pp. 1–14.

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World. New York University Press, 2020.

King, Tiffany Lethabo. The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press, 2019.

King, Tiffany Lethabo, and Frank Wilderson. “Staying Ready for Black Study: A Conversation.” Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness, Duke University Press, 2020, pp. 52–73.

McKittrick, Katherine. “Diachronic Loops/Deadweight Tonnage/ Bad Made Measure.” Cultural Geographies, vol. 23, no. 1, 2016, pp. 3–18.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.

Weheliye, Alexander. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Duke University Press, 2014.

Centering Black Studies Series

This cluster of syllabi centers the insights and contributions of Black Studies to rethink and remake Victorian Studies and the category of the “Victorian” itself. The syllabi do so by not only incorporating critical frameworks drawn from Black scholars like Christina Sharpe, Sylvia Wynter, Saidiya Hartman, and Tiffany Lethabo King (among others), but also by centering literary works by Black authors from the nineteenth century and showcasing the theoretical interventions they offer in their own right. Using these texts as the point of entry for thinking about texts from the white Victorian canon and an array of other texts by non-Black writers of color, each of the three courses engage in the forms of rigorous engagement, learning, and unlearning that are necessary to address and remedy the anti-Blackness that has structured our field.

Developer Biography

Anna Feuerstein is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Hawai'i-Mānoa. She is the author of The Political Lives of Victorian Animals: Liberal Creatures in Literature and Culture (Cambridge 2019) and is currently writing a book on the racialization of human-animal relationships within the cultural histories of British slavery and empire. Her recent publications on slavery and empire have appeared in Qui Parle and Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies. In 2019, she was awarded the Presidential Citation for Excellence in Teaching award.

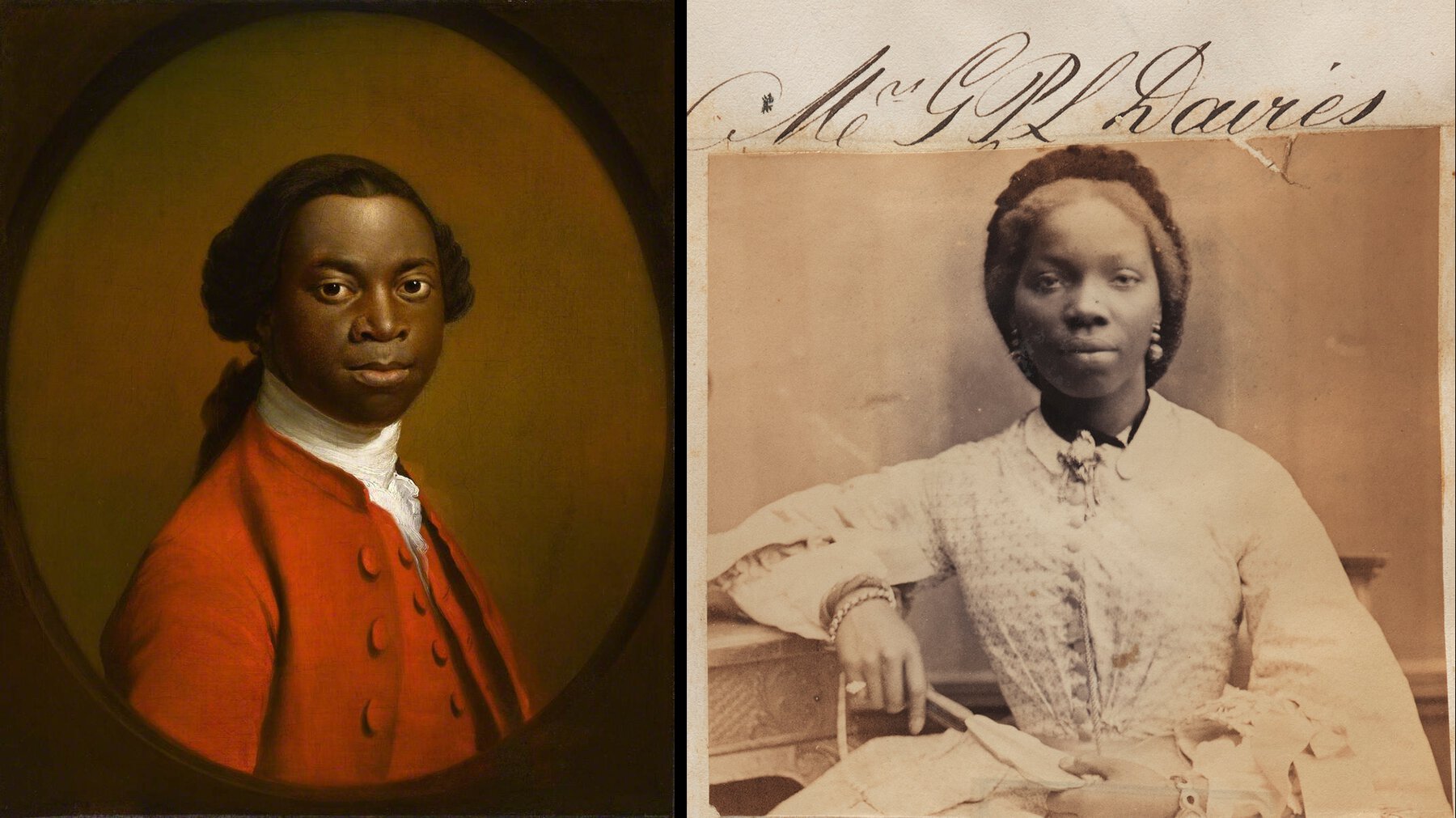

Tile/Header Image Captions

(Left) Ramsay, Allan. “Portrait of an African” [Ignatius Sancho Aka Olaudah Equiano]. Wikimedia Common, 1757. Royal Albert Memorial Museum, 14/1943. Public domain.

(Right) Silvy, Camille. Sarah Forbes Bonetta (Sarah Davies). 15 Sept. 1862. National Portrait Gallery, Photographs Collection, NPG Ax61384. Copyright National Portrait Gallery. Academic license for academic and non-commercial use.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Anna Feuerstein, dev. “Race, Trans-Atlantic Slavery, and the Empire.” Patricia A. Matthew, peer rev.; Ryan D. Fong, syl. clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2021, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/race_slavery_empire.html.