British Literature II: A Representative Survey

Syllabus Production Details

Developer: Riya Das Contact

Peer Reviewer: Jacob Romanow

Syllabus Cluster Developers: Kimberly Cox Contact | Riya Das Contact

Syllabus Guides: Pearl Chaozon Bauer Contact | Adrian S. Wisnicki Contact

Webpage Developer: Kristen Layne Figgins

Cluster Title: Beyond “Victorian” Literature

Publication Date: 2023

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

This British Literature II syllabus, which I developed and taught at Prairie View A&M University, a public Historically Black University in the United States, does not include a complete novel that becomes a major focus of the course. Instead, I opted to teach shorter texts and excerpts that allow for sustained interest and engagement from students that enable them to consider a wide range of authors and their respective socio-political situations with equitable rigor.

Prairie View A&M University's course catalog describes British Literature II as a “critical examination of poetry, prose, and drama from the neoclassical period to the present, emphasizing their historical and cultural contexts” (Prairie View A&M University Academic Catalog). This, in itself, beckons instructors to move beyond the confines of Victorian literature and canonical novel-length works. My British Literature II syllabus further destabilizes traditional expectations by embracing what I term the pedagogical politics of representation instead of accommodation.

Diversification of syllabi, despite instructors' best intentions, can often involve accommodating a brief sample of “other” literary works complementing lengthy canonical works considered indispensable for the field. This is symptomatic of the parallel “de facto social segregations” in the context of academic conferences, where “brown bodies are ghettoized in so-called special interest panels on postcolonial topics and spaces” (Chatterjee, Christoff, and Wong 374).

Representation, on the other hand, involves careful consideration of the opposing scopes at work in a British Literature II survey – in a semester system, there are about sixteen weeks at students' disposal to survey the colossal wealth of imperial literature. To devote three or more weeks of a survey course to a complete, well-known Victorian novel, customarily authored by white, English writers, is to help maintain the hegemony of the literary canon. Having students spend a majority of their temporal and intellectual currencies on one or two specific authors leads to a harmful misrepresentation of the literary landscape being surveyed. For example, students who experience British Literature II as eight weeks of Charles Dickens and George Eliot, along with a nebulous cluster of British, colonial, and postcolonial authors, may conceptualize the others as accommodated around rather than represented with the literary works by canonical authors.

My students in this course include a mixture of majors in English and other fields, and they are not required to take British Literature I prior to taking British Literature II. Therefore, we begin the course with a discussion of what canon and canonicity entails for a literary field. Then I introduce students to the British literary canon and we discuss the ways in which we will attempt to equitably survey British literature, as I have described above.

In my British Literature II syllabus, I arrange readings in rough chronological order, from a module titled “The Romantic C18” to a concluding module titled “C20 and C21: The New Fin-de-siécle.” Therefore, this syllabus is representative rather than accommodative in its effort to move beyond Victorian literature, the pliability of which is represented by both my syllabus and that of Kimberly Cox in our syllabus cluster. Each module in my syllabus constitutes specific critical/thematic frameworks through which students read clusters of short literary texts and excerpts.

For example, on Week 3, in the module “The Imperial C19: Condition of England,” students read contextual sources on the history of Victorian England, such as “What happened during the Victorian era?” which chronologically charts the British Empire's growth as a global industrial power amid the fragmentary abolition of slavery, famine, war, and colonial mutiny. Students then pair this contextual knowledge with a tactically selected excerpt from Bleak House featuring Charles Dickens' vivid description of London fog (61-62). This pairing enables students to interpret the passage in novel ways. For example, one student noted that Dickens' portrayal of fog not only underlines the hazardous environment of nineteenth-century London, but also the limited, “foggy” awareness of self-involved Londoners about the unjust imperial system they occupy the center of. On Week 4, in the module “Empire, Colonization, Translation,” students read translated poems from A Sheaf Gleaned in French Fields by Toru Dutt and the short story “Dream Life and Real Life: A Little African Story” by Olive Schreiner, broadening their understanding of nineteenth-century British literature as diverse in gender, genre, and national/racial identity.

A British Literature II syllabus without a complete novel not only allows a wider representation of individual authors, but also new frameworks of critique such as the module “Poets Laureate” on Week 5, which simultaneously introduces students to Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Rabindranath Tagore by purposefully pairing one poem by each. In this way, my syllabus uniformly positions the English Poet Laureate and the Indian Nobel Laureate in the imperial landscape of British literature, resisting the hegemonic temptation to supplement Tennyson's quintessentially “British” writing with an accommodative smattering of Tagore's “other” writing.

This also encourages students to seek and access new scholarly venues for research, such as the One More Voice digital humanities project, which is focused on racialized creators in British imperial and colonial archives and contains a bibliography of Tagore's works (Wisnicki). Furthermore, my syllabus invites students to participate in facilitating fair representation with the British Literary Profile Project, an assignment that asks students to research and discover British/colonial authors who are not necessarily part of the established Victorian canon.

In the module “The Victorian Woman Question” on Weeks 6 and 7, students read texts such as “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists” by George Eliot and an excerpt from The Romance of a Shop by Amy Levy, comparing a notably unconventional and established woman novelist's response to inferior literary works by women with another notably unconventional Jewish New Woman writer's fictional depiction of nineteenth-century women's entrepreneurship. This is followed by modules in which students survey diverse genres such as adventure and crime fiction, fin-de-siécle drama, and modernist and postcolonial literatures, with short texts by authors such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, and Chinua Achebe.

My syllabus concludes with the non-binary comic book writer Grant Morrison, leaving students with a reminder that the extensive and diverse scope of British literature stretches well into the twenty-first century, far beyond both the Victorian canon and the traditional temporal and formal structuring of course materials. Furthermore, the temporal punitive consequences of missing one week of a four-week module featuring a major text are essentially absent from my course. With new, concise readings assigned weekly, a student's return to class after a period of absence is less afflicted by the academic peril of lagging behind peers, especially when they may be facing difficult personal circumstances. This approach enables students to pick up at any point rather than having to catch up, which fosters their confident and sustained participation in class activities.

Thus, my method of surveying British literature with short and excerpted literary works promotes student success, particularly caring for those facing pandemic-related and other inequities. In her seminal book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Christina Sharpe recounts her experience of food and financial insecurities as an undergraduate student (4). For me, Sharpe's autobiographical example serves as encouragement to utilize syllabus-design as a tool to simultaneously undiscipline the Victorian classroom and care for diverse student needs in a minority-serving institution.

Works Cited

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Introduction: Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Victorian Studies, vol. 62, no. 3, Spring 2020, pp. 369–91.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Edited by Patricia Ingham, Broadview Press, 2011.

Dutt, Toru. A Sheaf Gleaned in French Fields. C. Kegan Paul & Co, 1880.

Eliot, George. “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.” The Common Reader, 2019.

“English Courses.” Prairie View A&M University Academic Catalog 2022–23 English (ENGL), 7 Aug. 2022.

Levy, Amy. “The Romance of a Shop.” Project Gutenberg, 2020.

Schreiner, Olive. Dream Life and Real Life. Roberts Brothers, 1893.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.

“What Happened during the Victorian Era.” Royal Museums Greenwich, 2021.

Wisnicki, Adrian. “Book-Length Published Works.” One More Voice, solidarity edition, 2022-23.

Beyond “Victorian” Literature Series

Not all faculty members with backgrounds in Victorian Studies have the opportunity to teach courses focused solely on either Victorian or nineteenth-century literature and writers. These syllabi offer models for pairing canonical Victorian texts with lesser-known, noncanonical, transnational, and contemporary texts or adaptations to extend conversations in courses that move beyond “Victorian” literature. By putting together traditional Victorian texts with Romantic, Modern, and Contemporary ones, these syllabi complicate the term “Victorian” as a designator of nationality, region, time period, and race. What is implied or excluded when talking about “Victorian” or “neo-Victorian” literature? The syllabi in this cluster offer illustrations of how antiracist and anticolonial methodologies can form the foundation of undergraduate classes not designated as either Victorian or nineteenth-century literature in college/university course catalogs – specifically, intermediate “British Literature II” and advanced “Multiethnic Literature” courses. Finally, they demonstrate how student-led research projects that ask students to delve into texts and writers beyond the British isles invite students into conversations about what literature gets taught and how course titles structure – and often limit – those decisions.

Developer Biography

Riya Das is Assistant Professor of English (British/World literature) at Prairie View A&M University. Her first monograph, Women at Odds: Indifference, Antagonism, and Progress in Late Victorian Literature, currently under advance contract at The Ohio State University Press and funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship, demonstrates the overlooked role of strategic antagonism and indifference in fashioning female progress. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, Victorian Literature and Culture, and other venues.

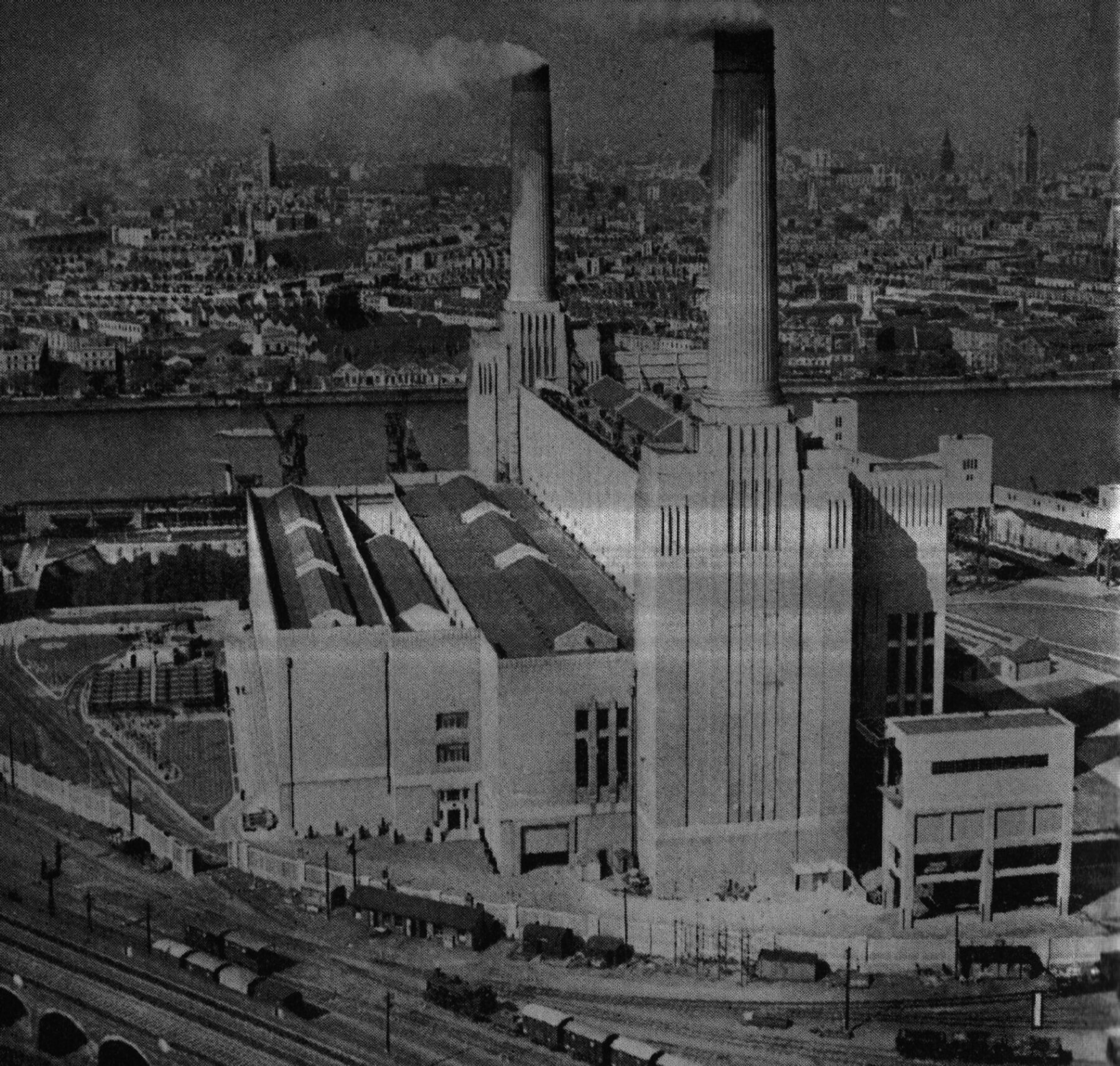

Tile/Header Image Caption

Dingley, Andy. Battersea Power Station, 1934 with Only Two Chimneys (Our Generation, 1938). 1934, Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Riya Das, dev. “British Literature II: A Representative Survey.” Jacob Romanow, peer rev.; Kimberly Cox and Riya Das, syl. clust. devs.; Pearl Chaozon Bauer and Adrian S. Wisnicki, syl. guides. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2023, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/representative_survey.html.