The Victorian and the Human

Syllabus Production Details

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

“The Victorian and the Human” equips students to answer the questions: What legacies and practices of white supremacy underpin the label “Victorian,” and how might we rethink the nineteenth-century British subject otherwise? Complementing Sukanya Banerjee’s recent interrogation of “who or what constitutes ‘Victorian’ or ‘British’ in the first place,” this course centers critical genealogies from Black Studies, postcolonial theory, and Black feminist thought to productively cast into crisis the construction of the human (925). These theories destabilize the white, able-bodied, sociopolitical citizen subject that liberal humanism engenders as and equates with the “Victorian” in the nineteenth century.

Reimagining the human begins with Sylvia Wynter’s theorization of the western man as an unnatural sociogenic ontological formation, upheld and reinforced by a stubborn interlocking system of epistemologies, power, and historically specific material conditions. To further rethink how the racialized human becomes – or is denied becoming – a subject and citizen with embodiment and agency, the course also integrates correlative critiques of biopolitics and subjecthood by Alexander Weheliye and Saidiya Hartman, respectively. Finally, the work of Christina Sharpe, Lisa Lowe, and Kathryn Yusoff situates this reimagined, problematized human in globalized social, economic, and environmental networks that are the bedrock of the Victorian empire.

This theoretical apparatus enables students to read white-authored Victorian texts as active participants in the project of rendering a specific mode of hegemonic humanity – revealing the dialectical relationship between humanization and dehumanization and other technologies of racialized violence in texts like The Moonstone, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poetry, and On Liberty. This course also surveys how nineteenth-century writers of color realize Wynter’s project of “counterhumanism” (298). The works of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, Toru Dutt, Ann Pratt, and Mary Seacole articulate assemblages of vitality, kinship, and care that can be read as insurgent models of personhood beyond that proffered by the “Victorian.”

This course is predicated on the conviction that studying race and Victorian literature is more pressing than studying race in Victorian literature. While the syllabus situates texts in their historically specific contexts, this course also takes its cue from Black studies by foregrounding the relationship between texts and knowledge production rather than knowledge produced. As such, this course trains students to notice and critique the ongoing, underlying processes that enable the legibility of race of and beyond biological or legal iterations. More broadly, this course aims to analyze a Victorian archive with the awareness that historical production is itself a racializing technology that, as practiced in the nineteenth century, inscribes and bolsters ideologies of natural and hierarchical racial differences.

To underscore this critical focus on knowledge production, this class normalizes transhistorical and interdisciplinary analysis. One of the places this focus is most evident is in the archives of both primary and secondary texts. The archive of primary texts surveys an array of genres, ranging from science writing to travelogue to serial novel to sonnet. This demonstrates how race can structure both form and content, and even texts that may not be “about” race are always participating in making race. Furthermore, the archive of secondary sources comes from numerous fields and includes traditional scholarly genres like monograph chapters or peer-reviewed journal articles as well as less-traditional genres like public-facing online publications.

The course archive also seeks to draw attention to, and subsequently disrupt, certain standard scholarly conventions, especially those of citation and gatekeeping. The archive of primary texts resists confining nineteenth-century writers of color to a token week or day. Instead, the syllabus is populated by equal proportion of white writers and writers of color and, furthermore, their work is read in close proximity — working against the colonial imaginary of siloed-off writers of color at the margins of the British empire. In addition, the archive of secondary scholarly texts is almost entirely scholars of color. For their writing projects, students are not required to do research beyond the archive this class provides them, and this is, in part, to give students practice citing scholars of color. The syllabus also calls for the instructor to teach students about citation politics and scholarly gatekeeping so that students can make more informed decisions about how they compile and deploy archives of their own in this class and others.

Finally, this course seeks to be accessible with a bent towards fugitivity. Logistically, this means that students can access all course texts at no cost and are evaluated via a transparent grading contract that rewards labor performed over opaque and subjective measures of intellect. Ideologically, this means that the course embraces, if not privileges, questions. Beyond a mere stylistic nod to Saidiya Hartman and others, the centrality of the speculative mode and questioning throughout the syllabus gives students clear entry points to what may seem like daunting texts as they simultaneously disrupt the expectations that generating knowledge must mean generating neat answers. To balance this attention to speculation, this syllabus articulates clear course outcomes that aim to contextualize and stabilize the oftentimes difficult-to-measure work of literary analysis and studying critical theory.

*

For writing this syllabus and rationale, I am indebted to informal yet formative intellectual contributions from Allison Fulton, Natalie Robertson, and Tori McCandless. These documents also benefit from the pedagogical excellence modeled to me by Dan Melzer, Claire Waters, Seeta Chaganti, Matthew Vernon, Mark Jerng, Elizabeth Freeman, and Erin Gray.

Works Cited

Banerjee, Sukanya. “Transimperial.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 46, no. 3–4, 2018, pp. 925–28.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation – An Argument.” The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, 2003, pp. 257–337.

Centering Black Studies Series

This cluster of syllabi centers the insights and contributions of Black Studies to rethink and remake Victorian Studies and the category of the “Victorian” itself. The syllabi do so by not only incorporating critical frameworks drawn from Black scholars like Christina Sharpe, Sylvia Wynter, Saidiya Hartman, and Tiffany Lethabo King (among others), but also by centering literary works by Black authors from the nineteenth century and showcasing the theoretical interventions they offer in their own right. Using these texts as the point of entry for thinking about texts from the white Victorian canon and an array of other texts by non-Black writers of color, each of the three courses engage in the forms of rigorous engagement, learning, and unlearning that are necessary to address and remedy the anti-Blackness that has structured our field.

Developer Biography

Ava Bindas is a Ph.D. candidate in English with an emphasis in Feminist Theory and Research at the University of California Davis. She is writing a dissertation about the uses of women’s ordinary, queer practices in Victorian novels of the recent past. She teaches in the University Writing Program and serves in multiple administrative capacities that seek to mitigate and obviate precarity for graduate students.

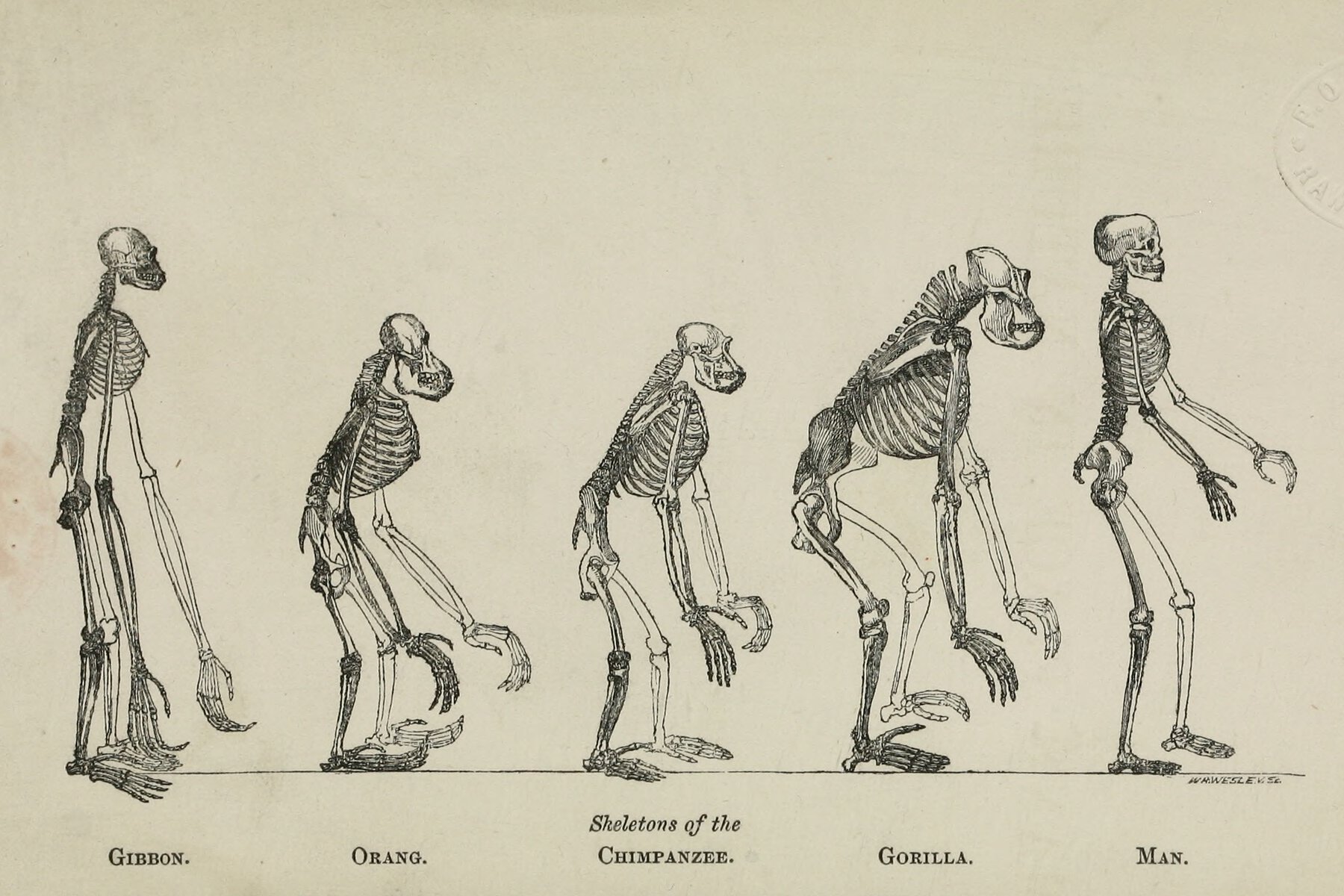

Tile/Header Image Caption

Hawkins, Benjamin Waterhouse. “Skeletons of the Gibbon. Orang. Chimpanzee. Gorilla. Man.” Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature, by Thomas Henry Huxley, Williams and Norgate, 1863, frontispiece. Public domain.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Ava Bindas, dev. “The Victorian and the Human.” Patricia A. Matthew, peer rev.; Ryan D. Fong, syl. clust. dev. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2021, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/victorian_human.html.