Constructing Religion and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Literature

Syllabus Production Details

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

This senior capstone undergraduate course is organized around a simple question: Can the literature of empire provide us a critical history of this thing we call “religion”? The answer, this course suggests, is yes. As historians of religion such as J. Z. Smith and David Chidester have pointed out, the modern concept of “religion” – most frequently understood as an anthropological category describing a certain set of human thought and action in terms of belief and norms of behavior – was constructed alongside colonial expansion.

Meanwhile, in a resonant vein, the postsecular turn of the 2000s, inaugurated by anthropologists and philosophers such as Charles Taylor, Talal Asad, and Saba Mahmood, has shown secularism to be an ideology in its own right, one that defines so as to manage “religion” in political life. And conceiving “secularism” as an ideology that defines, organizes, and manages certain norms of human behavior has particular salience when it comes to studying the exercise of imperial power.

So it’s curious that the recent return to race and empire in nineteenth-century literary studies has yet to grapple fully with these insights. Indeed, as scholars such as Gauri Viswanathan have observed, religion still remains the “blind spot of literary studies” (Allan 255; see also Werner and Winick). Meanwhile, the growing subfield of religion and literature in nineteenth-century studies remains somewhat nation-bound, focused mostly on British Christianity within Britain.

Thus, I’ve designed this course not only because it’s important for students to know this literary history. I also hope students will seize on an opportunity to make a meaningful contribution to the “undisciplining” of nineteenth-century literary studies (Chatterjee et al.) – that is, to think about the unmarked universals that underlie our own approaches to this period, in this case in regard to how we tend to think about the concepts of “religion” (e.g., often as a byword for Western Protestant Christianity) and “secularism” (e.g., as the absence of religion rather than a concept with profound normativizing force).

I pitch “Constructing Religion and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Literature” as disrupting the “secularization narrative” that tends to govern Victorianists’ treatment of religion. Whether or not undergraduates are familiar with the discourse surrounding secularization, I suspect that many of them have imbibed some version of this narrative, which posits that the expansion of liberal governance, the advent of the Higher Criticism, and scientific advancement (particularly Darwinism) together ushered in an Age of Doubt or, as Callum Brown puts it, “the death of Christian Britain.” And what I want students to understand is that while the recedence of religion from public life is one story we can tell about nineteenth-century “religion,” it’s certainly not the period’s only story. In fact, to take a global view is necessarily to see how blinkered this narrative actually is.

Thus, this capstone undergraduate course offers something of a contrapuntal literary history to the more common narrative of religion’s decline. By way of known and relatively unknown texts, known and unknown historical moments, it proposes instead that this thing we call “religion” is relocated and redefined by imperialism. Moreover, in taking students beyond the faith/doubt binary, it shows them how a diverse set of nineteenth-century authors took inspiration from and intervened in this relocation.

For the sake of organization and convenience, the course is roughly chronological. However, I try to avoid implying that something as inchoate as “religion” can be narrated in a linear or progressive fashion. Instead, taking a cue from the anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler, I structure the course to consider “recurrent themes” (7), presenting what I hope will strike students as a synthetic depiction of links between religion and imperialism rather than a straightforward account of change over time.

The first week provides the groundwork for the course by introducing students to key theoretical texts that denaturalize the terms “religion,” “religions,” “world religions,” and “secularism.” Then, the next two weeks revisit more familiar texts and contexts – Orientalism and the missionary movement, Sydney Owenson’s The Missionary and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre – asking students to consider the unique ways each constructs its notion of what constitutes “religion,” how “religion” proper ought to be studied or practiced, and the extent to which “religion” is a universal phenomenon or something belonging solely to so-called “advanced” civilizations (while “less civilized” ones might have, for instance, “superstition” or “primitive religion”).

In this unit, then, we focus on the ways that an emergent idea of “religion” came to be bound up with nineteenth-century racial formations, for example, in the enthusiasm among Orientalists’ for William Jones’s Indo-European thesis, which contributed to aligning Christianity with Aryanism, distancing it from Semitism, and justifying European colonization, particularly in South Asia (Olender).

The next few weeks introduce students to perhaps less well-known texts: the Malay classic, The Hikayat Abdullah by the Muslim scribe and translator, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir; the unfinished novel, Bianca, Or, The Young Spanish Maiden, by the accomplished South Asian poet, Toru Dutt; Krupabai Satthianadhan’s Saguna, the first autobiographical novel in English by an Indian woman; and the writings of leading figures of the Hindu reform movement, the Brahmo Samaj. We start from the premise that these texts must be understood in reference to what these writers took to be a distinctly Western iteration of Christianity fundamentally intertwined with the dynamics of imperialism.

We go on to ask, then, how do these texts represent, respond to, or transfigure this alliance between an emerging modern concept of “religion” and imperialistic nationalism? Moreover, if the “discourse of world religions came into being as a means of trying to classify and control non-white alternatives […] to (white) Christianity” (Nye 229), how do these texts articulate alternate taxonomies and definitions of “religion”?

The final third of this course explores relatively more “esoteric” spiritualisms as well as new religious movements of the late nineteenth century: spiritualism, theosophy, and the rise of the “global guru” figure, to use the term of literary critic Srinivas Aravamudan. We close the class by looking at one of the afterlives of these movements in the form of Paramahansa Yogananda’s Self-Realization Fellowship, which Yogananda considered a “missionary” enterprise to bring spiritual enlightenment to the West (and which scholars such as Anya Foxen credits with introducing yoga to America).

The design of this course is significantly influenced by my teaching context. Wheaton College is a small liberal arts college in southeastern Massachusetts. Facing the same financial challenges as many tuition-dependent small colleges (particularly those in the oversaturated New England marketplace), Wheaton in recent years has adopted a so-called career-connected identity to attract students (Wheaton College). The consequent curricular and marketing overhaul has impacted how I create assignments. For instance, my students expect that even if course content might not have immediate applicability to near-term professional goals, assignments and skills cultivated over the course of the semester certainly will.

In part to meet this expectation (and in part because I believe it’s a productive, fun challenge in its own right), I include a collaborative essay assignment that requires students to research and write together as they make a nineteenth-century sermon or religious essay accessible to a broad public audience. Such an assignment tends to appeal to students interested in library and museum studies as well as those thinking about careers in public relations and marketing, as they can clearly see how the skills cultivated (e.g., working within and managing a team; making dense, specialized material more digestible to non-specialized audiences; and so on) transfer to a workplace.

The emphasis on career-connectedness influences my course design in another way. Curricular requirements and the campus culture more broadly encourage students to pursue internships and other forms of experiential learning, a pressure that becomes especially acute in the senior year. Students at Wheaton have always had significant responsibilities outside their coursework, but I find this to be especially the case in the past two years. I try, then, to build in-class sessions focused solely on synthesizing knowledge, discussing arguments, developing drafts, and workshopping writing, as students often need dedicated in-class time to develop their ideas or meet with fellow group members.

Future versions of this syllabus, I imagine, will devote even more time to in-class brainstorming and writing if only to mitigate the impact of ChatGPT on student writing. As the historian Steven Mintz has remarked, “Writing is not merely a mode of communication. It’s a process that, if we move beyond simple formulas, forces us to reflect, think, analyze, and reason.” By having students collectively work on their writing in class, my hope is that they’ll come to appreciate writing as valuable to their own thinking process rather than simply a task imposed on them.

I recognize that this course has an ambitious reading load, and this is by design. Rather than trimming course readings, I’ve recently begun experimenting with having students determine in the first week of classes which texts they will read or opt to skip, depending on their personal interests and schedules. The idea is that each student will have the syllabus as a resource for future reading beyond the semester, even as they construct their own pathway of reading during the semester. I’ve had some setbacks and successes in this experiment, but I noticed my seniors in particular seem to appreciate this structure, seeing it as an opportunity to co-create with me their capstone experience.

I am still thinking through issues of accountability (e.g., Once a student has created a reading pathway, how do we ensure follow-through on this plan?) and assessment (e.g., How do I measure student understanding of course materials in this scheme?). Luckily my senior capstone courses have enrollments from 6-15 students – a class size that permits flexibility, experimentation, adaptation, and plenty of one-on-one check-ins. As of now, my limited experiments in reading pathways leads me to think that this structure perhaps can only be fully successful in small classes composed of highly motivated students, such as the senior capstone class.

Ultimately, I want my senior students to realize that words they tend to think of as neutral descriptors exert real normativizing power over the phenomena they purportedly just describe. In the case of “religion,” this ideological work often entails apprehending diversities of religious thought and practice by way of a comparativism beholden to a distinctly Western Christian framework (see Masuzawa). By examining the extent to which the consolidation of the concepts of “religion” and “secularization” happened in concert with imperialism, my hope is that students develop alternate vocabularies and vantages by which to better encounter the tremendous diversity of faith-based movements, ethics, literatures, and practices in the nineteenth century and beyond.

Works Cited

Allan, Michael. “Heterodox Philology: A Conversation with Gauri Viswanathan.” Philological Encounters, vol. 6, no. 1–2, 2021, pp. 243–64.

Aravamudan, Srinivas. Guru English: South Asian Religion in a Cosmopolitan Language. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Asad, Talal. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford University Press, 2003.

Brown, Callum G. The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation, 1800–2000. Routledge, 2001.

Chatterjee, Ronjaunee, et al. “Undisciplining Victorian Studies.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 10 July 2020.

Chidester, David. Empire of Religion: Imperialism and Comparative Religion. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Foxen, Anya P. Biography of a Yogi: Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Mahmood, Saba. Religious Difference in a Secular Age: A Minority Report. Princeton University Press, 2016.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Mintz, Steven. “Writing Is Thinking.” Inside Higher Ed, 2 Nov. 2021.

Nye, Malory. “Race and Religion: Postcolonial Formations of Power and Whiteness.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 31, no. 3, 2019, pp. 210–37.

Olender, Maurice. The Languages of Paradise: Race, Religion, and Philology in the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, 1992.

Smith, Jonathan Z. “Religion, Religions, Religious.” Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion, University of Chicago Press, 2004, pp. 179–96.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. University of California Press, 2002.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Harvard University Press, 2007.

Werner, Winter Jade, and Mimi Winick. “How to See Global Religion: Comparativism, Connectivity, and the Undisciplining of Victorian Literary Studies.” Modern Language Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 4, 2022, pp. 499–520.

Wheaton College. Home. Wheaton College, IL, 2023.

Religion, Secularism, Empire Series

Taking a cue from Gauri Viswanathan’s observation that religion remains “the blind spot of literary studies” (Allan 2021), this syllabus cluster posits that understanding Victorian imperialism requires centering the category of religion. Too often we cast religion as the premodern background against which Victorian modernity unfolded. We describe the rearguard battles that Christian dogma fought against an advancing Darwinian science or how the traditional religions of Indians or Africans came into conflict with imperial rule.

The syllabi in this cluster, by contrast, treat religion as a dynamic and evolving set of ideas that were central to both imperialism and anti-imperialism. They explore how changes to the Western category of religion – specifically, the modern idea of religion as a matter of belief – structured how Victorians understood subjectivity, civilization, and cultural difference.

The syllabi also consider how reappraisals of Christianity, Buddhism, or Hinduism by colonial subjects drove anticolonial thought during the period. And they show how debates over the translation and meaning of religious texts helped birth the idea of “world literature.” By enriching our critical vocabulary for talking about religion and empire, these syllabi offer students new frameworks for understanding the religio-political dimensions of literature as well as the aesthetic interventions of religious texts and practices.

Developer Biography

Winter Jade Werner is an Associate Professor of English and the Jane E. Ruby Chair in Humanities and Social Sciences at Wheaton College in Massachusetts. She is the author of Missionary Cosmopolitanism in Nineteenth-Century British Literature (OSUP 2020), and with Joshua King, the co-editor of Constructing Nineteenth-Century Religion: Literary, Historical, and Religious Studies in Dialogue (OSUP 2019). Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Comparative Literature, MLQ, Literature and Theology, Nineteenth-Century Literature, and elsewhere. Her current research focuses on the role of foreign missionary presses in consolidating nineteenth-century ideas of “world literature.”

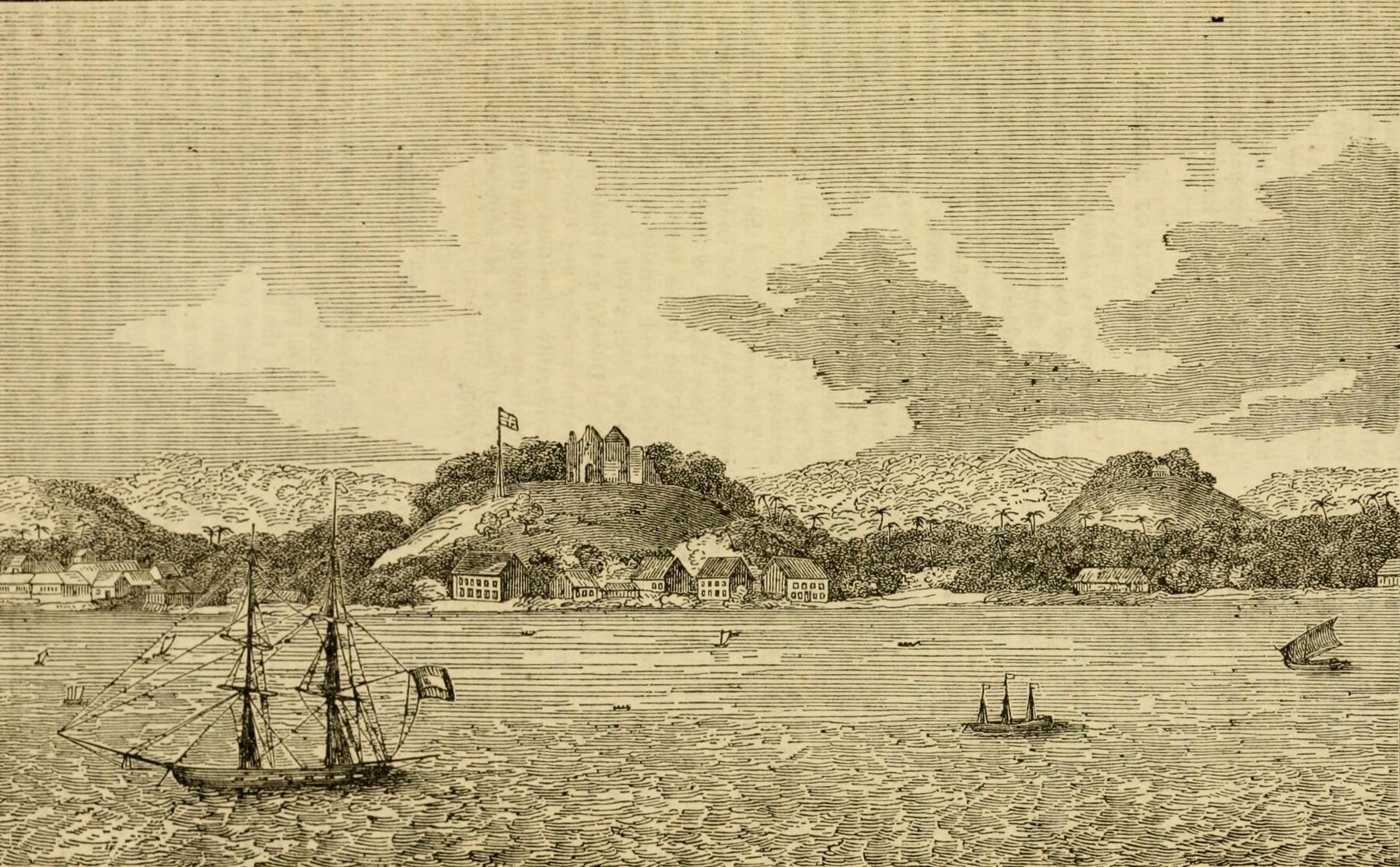

Tile/Header Image Caption

Once Known Artist. “Malacca in 1831.” July 1831. Wikipedia. Public domain.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Winter Jade Werner, dev. “Constructing Religion and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Literature.” Charles LaPorte, peer rev.; Sebastian Lecourt, syl. clust. dev.; Sophia Hsu, syl. guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2024, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/constructing_religion.html.