Religion and the Transimperial: Literatures of Faith, Conquest, and Resistance

Syllabus Production Details

Developer: Padma Rangarajan Contact

Peer Reviewer: Charles LaPorte

Syllabus Guide: Sophia Hsu Contact

Webpage Developers: Kristen Layne Figgins, Adrian Wisnicki

Cluster Title: Religion, Secularism, Empire

Publication Date: 2024

Syllabus Overview

Download the peer-reviewed syllabus: PDF | Word

The goal for this undergraduate seminar is to encourage students to consider as much as possible how religion can illumine the transimperial. It takes seriously Sukanya Banerjee’s argument that a ”transimperial analytical framework […] places Britain in constant tension and connection with its imperial constituencies […] by continually questioning the discrete solidities of the (British) nation and placing it in inexhaustible relation of contiguity and interconstitutiveness with the empire ‘out there’” (925). Using religion and its central place in the cultural life of the nineteenth century as its analytical framework, the class braids together literature of the “metropole” and “periphery” to demonstrate their interdependency.

I hope to demonstrate to students that the religious transformations of the late nineteenth century were the products of local sociopolitical upheavals (e.g., the growing effects of urbanization and industrialization) as well as of colonial intellectual exchange. By transformations, I emphatically do not mean linear progress toward secularization. Rather, I mean the growing influence of nonconformism, mysticism, and a political Irish Catholicism. Working against a persistent tradition in which imperial and domestic cultures are considered separately, the class will present the British Empire as effectively that: a sociopolitical entity in which Britishness and imperialism are not seen as accidentally contiguous (as per the axiomatic understanding of how the Empire came to be) but as a symbiotic whole.

Recent critiques of the assumed and undisputed rise of secularism in nineteenth-century Britain, and of the triumph of liberalism, have contributed to a far more nuanced understanding of the relationship between religion and secularism as well as between liberalism and empire. Uday Singh Mehta notes that, although “geometrical truths bec[a]me the hallmark of liberal politics,” this was countered by those were able to “articulate the conditions […] for what amounts to a conversation across boundaries of strangeness” (214, 216). Mehta here refers specifically to Edmund Burke’s reaction to the late-eighteenth-century culture of the East India Company. But recentering the importance of religion in the cultural life of the nineteenth century allows us to critique how changing attitudes toward religion were inspired by imperial contact, allowing for strange conversations and conversations with strangers.

The second objective of this class is to highlight the intersection between nascent anticolonial activity and religious reformation. It is no accident as Bhikhu Parekh notes, that “almost every major advocate of terrorism either wrote a commentary on or extensively quoted from” the Bhagavad-Gita (89). In a late-nineteenth-century context, Elleke Boehmer’s work on cross-imperial networks is particularly helpful. Boehmer’s Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890-1920: Resistance in Interaction (2002) studies political alliances between different imperialized peoples, stressing “;how definitive concepts of self-realization often seen as originating within European political traditions […] were critically appropriated and remade […] through borrowing, exchange, and even collaboration between anti-colonial regions” (2).

For the purposes of this class, I’ve chosen to highlight the affinities between Irish Catholic and Hindu nationalisms. Additionally, the class traces connections between the advent of muscular Christianity and the specific discourse of the so-called “New Imperialism” in Africa. It also touches on Hinduism’s and Buddhism’s impact on late-nineteenth-century spiritualism, mysticism, and occult movements like Theosophy. In place of a teleological model of progressive secularism, my goal is to offer a far more conflicted history of colonialism’s relationship to the postsecular.

The course’s third aim is to consciously consider how genres developed in response to imperialism. I also hope to demonstrate to students how the rise of “canonical” literature is tied to these generic considerations. I’m inspired here by Srinivas Aravamudan’s reclamation of oriental tales in Enlightenment Orientalism, and the texts I’ve chosen extend Aravamudan’s arguments about neglected forms of fiction to include religion. Although studies of the development of the novel have generally adhered to György Lukács’ insistence that the novel “is the epic of a world that has been abandoned by God,” reading outside the canon of domestic realism into other genres – e.g., the adventure tale, the historical novel – reveals an alternate history, both of the novel form and of this teleological narrative of secularization (88). In contrast to the arbitrary flattening of religious cultures that, as Charles LaPorte argues, is a consequence of the Victorian secularization narrative (279), the texts I’ve chosen sharply demonstrate how these religious cultures are not modernity’s antithesis but its constant companion.

The course begins with a series of poems that encapsulate many of the course’s governing topics, including Gerard Manley Hopkins’s and Swami Vivekananda’s strikingly different ways of describing divinity. It then moves to an unusual choice: George Eliot’s Adam Bede, which I will present to the class as an important precursor to H. Rider Haggard’s She.

Eliot’s novel and Haggard’s represent opposite ends of the literary spectrum: canonical novels versus adventure novels, realism versus fantasy, “metropole” versus “periphery.” But Adam Bede is also a novel bookended by empire; it begins with the image of the Egyptian sorcerer and ends with Hetty Sorrel‘s transportation to Botany Bay. Contrast this with the moment in She when Horace Holly and his companions are surrounded by the hostile jungle and take comfort in a tin of potted tongue. The overtly spiritual concerns of Adam Bede additionally form a useful contrast to She. Amid descriptions of crocodile hunts and human torches, Haggard’s novel is notable for the multiple conversations between Holly and the sorceress Ayesha on religion. Furthermore, it is an example of what Simon Magus terms the “Imperial Occult,” “an epiphenomenon of the counter-invasion and reverse-missionising of religious ideas on the colonial periphery” (xiv). Along with offering vivid accounts of the turns of religious discourse in the period, both texts offer usefully contrasting examples of the weird intimacies of nation and empire.

The relationship between work and religion that is so central to Eliot’s novel takes an explicitly colonial turn in Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Thomas Hughes’s novel demonstrates how rural England is connected to the Empire through education and how Christian virtues were easily transposed into imperial ones. This is depicted in Tom’s relationship with the pious George Arthur, who, along with Thomas Arnold, acts as the civilizing, Christianizing influence on the savage but reformable boys. The subsequent poems and essays by Henry Newbolt and David Livingstone underscore the influence of Muscular Christianity while, opposingly, the readings by Subramania Barathi and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay explicitly respond to this narrative of benevolent colonialism with their own vision of how spirituality compels political action.

In several of the above texts, religion ennobles imperial duty. In contrast, Thomas Moore’s The Fire Worshippers depicts the religious and political disenfranchisement of Catholic Ireland as genocide. It is a remarkable text that anticipates the rise of Fenian terrorism at the end of the century. Rudyard Kipling’s “The Undertakers,” which foregrounds the clash between Indian superstition and British innovation, is also an example of how narratives of the Sepoy Rebellion (Mutiny) were woven into British consciousness. In contrast to Kipling‘s binaries, the section of the course on comparative religion highlights the late-nineteenth-century interest in religious syncretism with all of its promises and, as Gauri Viswanathan has detailed, its problems. Of these readings, Sri Aurobindo‘s “Lines of Ireland” provides a particularly interesting example of how transimperial connections fostered anticolonial solidarity, serving as a kind of companion piece to Moore‘s brutal orientalist fantasy.

The final readings for the course pair Christina Rossetti and Toru Dutt. While neither Rossetti‘s nor Dutt‘s poems are explicitly religious, they subtly explore faith, divinity in nature, and, in the case of Dutt, the overlapping of Christian and Hindu religious imagery. These poems serve as a contrast to the explicit spirituality of the poetry in Week 1 and offer students a chance to bring the knowledge they‘ve gained in the previous weeks to the fore.

Because the class ranges so far afield in terms of place and history, I have arranged the course around a series of reading responses that will allow them to make connections over the duration of the term and as they work toward their final project. The final project has two parts: a traditional paper and a collaborative reflective assignment where students work on developing different concept maps (using the online mapping tool Coggle) that trace the evolution of core course concepts over the assigned readings.

Works Cited

Aravamudan, Srinivas. Enlightenment Orientalism: Resisting the Rise of the Novel. University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Banerjee, Sukanya. “Transimperial.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 46, no. 3–4, 2018, pp. 925–28.

Boehmer, Elleke. Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890-1920: Resistance in Interaction. Oxford University Press, 2002.

LaPorte, Charles. “Victorian Literature, Religion, and Secularization.” Literature Compass, vol. 10, no. 3, Mar. 2013, pp. 277–87.

Lukács, Georg. The Theory of the Novel. Translated by Anne Bostock, The MIT Press, 1971.

Magus, Simon. Rider Haggard and the Imperial Occult: Hermetic Discourse and Romantic Contiguity. Brill, 2021.

Mehta, Uday Singh. Liberalism and Empire: A Study in Nineteenth-Century British Liberal Thought. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Parekh, Bhikhu. “Gandhi‘s Theory of Non-Violence: His Reply to the Terrorists.” Terrorism: Critical Concepts in Political Science, edited by David C. Rapoport, vol. 2, Routledge, 2006, pp. 88–106.

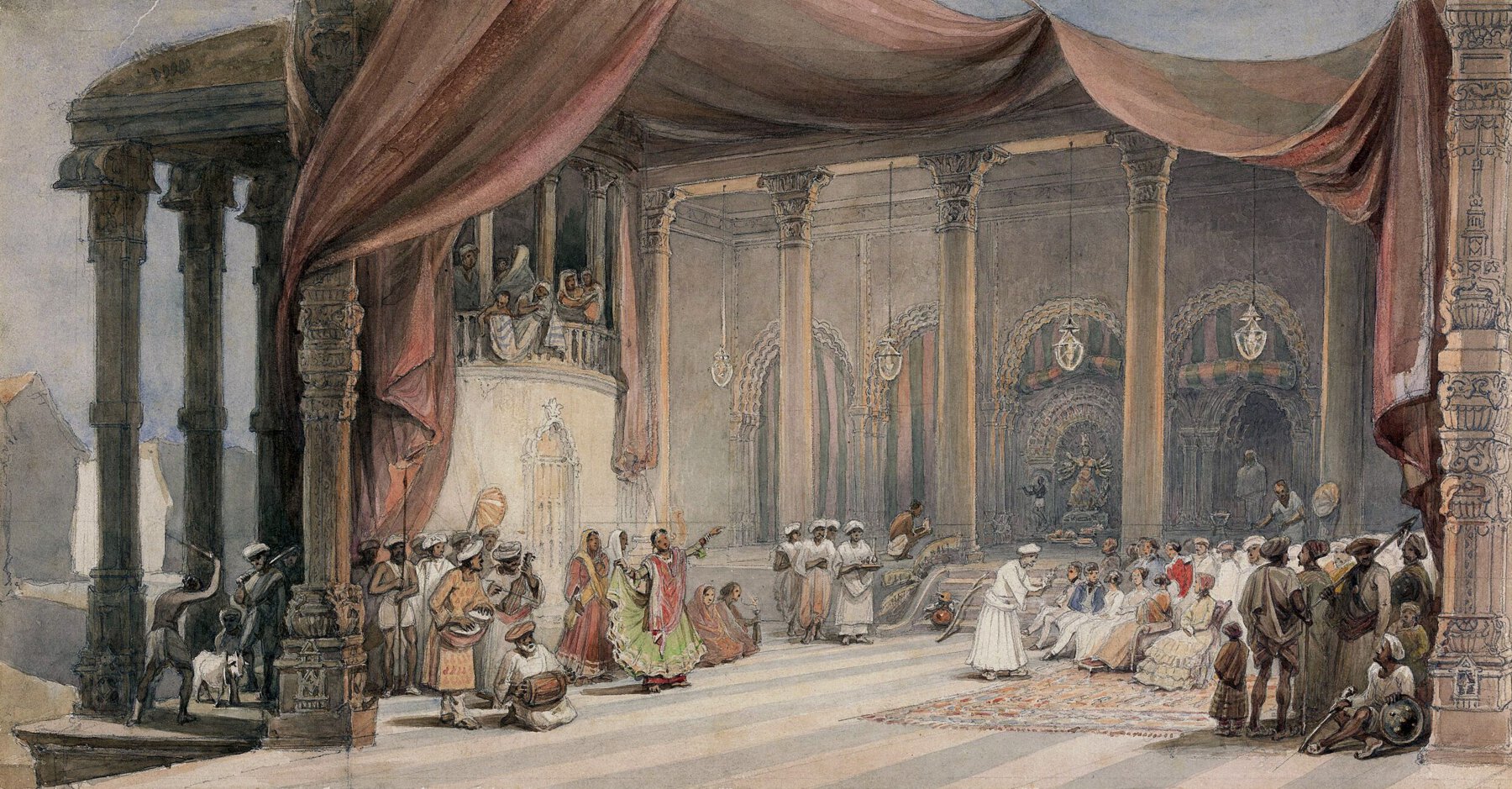

Prinsep, William. Europeans Being Entertained by Dancers and Musicians in a Splendid Indian House in Calcutta During Durga Puja. 1849 1830. Wikipedia.

Viswanathan, Gauri. “Beyond Orientalism: Syncretism and the Politics of Knowledge.“ Stanford Humanities Review, vol. 5, no. 1, 1995, pp. 18–32.

Religion, Secularism, Empire Series

Taking a cue from Gauri Viswanathan’s observation that religion remains “the blind spot of literary studies” (Allan 2021), this syllabus cluster posits that understanding Victorian imperialism requires centering the category of religion. Too often we cast religion as the premodern background against which Victorian modernity unfolded. We describe the rearguard battles that Christian dogma fought against an advancing Darwinian science or how the traditional religions of Indians or Africans came into conflict with imperial rule.

The syllabi in this cluster, by contrast, treat religion as a dynamic and evolving set of ideas that were central to both imperialism and anti-imperialism. They explore how changes to the Western category of religion – specifically, the modern idea of religion as a matter of belief – structured how Victorians understood subjectivity, civilization, and cultural difference.

The syllabi also consider how reappraisals of Christianity, Buddhism, or Hinduism by colonial subjects drove anticolonial thought during the period. And they show how debates over the translation and meaning of religious texts helped birth the idea of “world literature.” By enriching our critical vocabulary for talking about religion and empire, these syllabi offer students new frameworks for understanding the religio-political dimensions of literature as well as the aesthetic interventions of religious texts and practices.

Developer Biography

Padma Rangarajan is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Riverside, where she specializes in nineteenth-century British literature and colonial epistemologies. She is the author of Imperial Babel: Translation, Exoticism, and the Long Nineteenth Century (Fordham 2014). She has published essays in English Literary History, English Language Notes, Studies in Scottish Literature, Nineteenth Century Literature, Romanticism, Keats-Shelley Journal, and Romantic Circles. She is currently working on a project about colonial terrorism in the nineteenth century.

Tile/Header Image Caption

Prinsep, William. Europeans Being Entertained by Dancers and Musicians in a Splendid Indian House in Calcutta During Durga Puja. 1830-1849. Wikipedia. Public domain.

Page/Syllabus Citation (MLA)

Padma Rangarajan, dev. “Religion and the Transimperial: Literatures of Faith, Conquest, and Resistance.” Charles LaPorte, peer rev.; Sebastian Lecourt, Winter Jade Werner, syllabus cluster devs.; Sophia Hsu, syllabus guide. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2024, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/syllabi/religion_transimperial.html.