Colonial/Postcolonial Texts of the “Dark Continent”

Lesson Plan Production Details

Developer: Oishani Sengupta Contact

Peer Reviewers: Barbara Barrow, Renée Fox, Cherrie Kwok, Diana Rose Newby, Matthew Poland, Jessie Reeder, and Emma Soberano

Lesson Plan Cluster Developer/Copyeditor: Ryan D. Fong Contact

Webpage Developer: Ava K. Bindas

Cluster Title: Undisciplining In and Through Contemporary Texts

Publication Date: 2024

Goals, Questions, and Usage

This lesson plan centers the idea that the idea of “race” in the nineteenth century gained its central role in global politics through modes of representation and circulation. The units in this lesson explore the creation of just such a popular representation – that of Africa as a “dark continent” full of dangerous beasts, cannibalistic tribes, and wildernesses infested with deadly parasites. Created at the precise moment when Europe shifted gears from the transatlantic slave trade to the scramble for physical control of the African continent (Brantlinger), this racialized image was created and shared across empire’s center and peripheries.

Travelogs, adventure narratives, advertisements, and news united discourses on racial difference, whiteness, indigeneity, labor, extraction, nationalism, and cultural hybridity. In these diverse texts threading together the print networks of the empire, “Victorian” values and social perceptions remain a powerful connecting thread. Whether they are being upheld, resisted, or mocked, the effects of an ideological frame pervade this multilingual archive of “dark continent” literature.

In Section 2, I have provided a range of options in which these readings could be organized – through lesson plans, discussion questions, and multimodal assignments. Our goal is to discuss the British empire’s textual production of Africa as a racialized geography through a vast trove of print materials, illustrations, photographs, newspaper reports, etc. Section 3.1 looks across an array of materials that span the print markets of Britain, the U.S.A, South Africa, East Africa, India, and many other locations.

This archive introduces students to the ways in which impressions of Africa were crafted in print culture. Discussions of the popularity of David Livingstone’s travelogues and cult-like status of Henry Rider Haggard’s novels – and how they have changed since then – could be enriched by looking at illustrations and reprint editions, while newspapers and magazine entries can show how Africa was presented to the public.

While we initially begin by examining the construction of Africa as exploitable racialized geography, we later read elements in the module that can weave together the responses of Africans and South Asians as counterpoints to these colonial genres. Section 3.2 explores Indigenous African responses to both travel narrative genre and the African romance narrative.

The self-reflexive critique in these texts – Plaatje’s Mhudi, for example – show not only how deeply embedded the discursive construct of Africa became in a global cultural context, but the variety of ways in which African writers directly and indirectly fractured its hypotheses. Horton’s West African Countries and Peoples, for instance, was published before Henry Morton Stanley’s major works, and it explicitly charges Europeans with racism in sections titled “Exposition of Erroneous Views Respecting the African” and “False Theories of Modern Anthropologists.”

Section 3.3 presents two famous Bengali adaptations of the imperial romance genre, where traditional elements of exploration, mineral extraction, and interracial encounter are complicated by the emerging politics of decolonization, indentured labor, and the creation of new middle classes in the global south. Reading these texts together produces a “widening” of our critical and historical lenses (Banerjee, Fong, and Michie) as we investigate empire’s impacts in terms of geography and genre.

Some broad questions that emerge move us beyond the limits of transatlantic racial relations and into an Indian Ocean framework, highlighting South-South relations as central to race-making. How do colonial print imaginaries of Africa circulate in the Indian Ocean world (Hofmeyr)? What forms of transnational and transcultural contact between Asian and African populations do they generate (Lowe)? And finally, what happens when the figure of the white imperialist is transposed upon that of the abjected South Asian laborer (Sengupta)?

These concerns inform our engagement with Bengali print culture about Africa in the twentieth century (Mowtushi; Banerjee and Basu), where Africa became the site of exploring ideas of primitivity and modernity during the era of active decolonization in the subcontinent (Burton). Examining the impact of old modes of racialization on newer texts shows the resilience of Victorian narrations of race and coloniality in the pre- and post-Independence contact across the Indian Ocean world.

While primary texts explore the granular processes shaping the creation of an imperialist imagination, the list of secondary readings cut across individual texts, illuminating certain transhistorical trajectories that illustrate the successful and failed mobilities of the British empire (Banerjee). For that reason, it is important not to generalize the lessons of this module, particularly it is hard to cast a single experience as necessarily representative of massive phenomena like indentureship or settler colonialism.

Resisting that urge, this module encourages students to look for, pay attention to, care about, and recover individual stories and textured experiences of extraction under the aegis of colonialism’s narrative genres. Just as images of Africa cannot be used as a generalization of the continent, similarly, the perspectives of individual Bengali writers – though writing within a milieu – must be given individual attention instead of being granted value as appropriate representatives of a class of fiction. Read in this way, these texts offer critiques of empire that can be aggregated to develop a wider perspective of the nineteenth century and its legacies over time.

A note about images: I have not provided an extensive list of visual materials especially since the archive of visualizing empire is so vast and easily accessible. Most of the primary texts come with illustrations. The issue is not the paucity of illustrations but the recognition of their disturbing nature and the fact that they emerge out of a complex epistemological tradition of remaking an “image-Africa” (Landau) for cultural and political gain.

Lesson/Module Ideas

King Solomon’s Mines and Chander Pahar

These two texts pair very successfully, since Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novel clearly cites H.R. Haggard’s earlier work. The structure of the journey bears many similarities – a Portuguese man brings news of hidden diamonds, a pact is formed among explorers, they experience many challenges (animal attacks, violent conflicts with Indigenous peoples, entrapment inside caves) and finally rescue the wealth.

While drawing attention to the exact echoes can lead to a productive discussion of the circulation of imperial genres, another path might be to explore how these apparently similar moments are mobilized to express very different political ends in the two texts. If the texts are used to chart a shifting geography of South-Central Africa, then Melissa Free’s lesson plan on “South Africa 1820-1930” could be placed very productively in conversation with them.

One approach would be to pair specific scenes (the arrival of the sick José/the arrival of the sick Alvarez; the two sequences of being trapped in a cave and finding diamonds). Another point of entry may be to use historical sources/archival documents (see 5.1-2) to contextualize the different moments of empire these texts reference – the creation of a settler state in South Africa vs. the interwar period, decolonization, and changing politics of labor and immigration.

Discussion Questions

- How does the figure of Quatermain have an afterlife in the minds of young English-educated colonial subjects like Shankar? What are the conditions preventing him from/enabling him from becoming like Quatermain?

- How does the relationship between Shankar and Diego Alvarez represent a mutation of the homosocial logics of the bond between Haggard’s “three white men”? In what way does it restage the relationship between the trio and the figure of Umbopa/Ignosi?

- What do the representation of Indigenous Africans in the two texts tell us about what the authors believed/knew/read about Africans? Discuss the different levels of engagement the authors had with the communities they are describing and what effect that might have on characterization?

- Compare the illustrations of the Bengali text with the images in the original Cassell and Co. illustrated edition. What are the technological differences between the two? What do the mis-en-scène of the respective images and the reproduction processes indicate about the infrastructure of the print networks that produced the two texts?

- Since both have been adapted for film, what can you say about how these narratives have been remediated as modern fantasies of producing racialized geographies?

Mitra, “Mosquito” and “Glass” in Mosquito and Other Stories; Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents

The two stories, “Mosquito” and “Glass,” offer an excellent glimpse into the neo-imperial re-imagining of Africa in a post-World War II moment. The figure of Ghanada and his exploits in the Sakhalin islands and Angola offer rich interlocutory possibilities with Lisa Lowe’s work particularly as they highlight the violent creation of the intercontinental “intimacies.” Both Ghanada and the anticipated readers of the stories exemplify, to some extent at least, the “imperial connections” that Lowe draws attention to, in describing the affiliation with Thackeray acknowledged by C. L. R James.

Not only do the work’s readers and characters sketch the survival of an imperial genealogy, Ghanada embodies the dreams and aspirations of the classic figure of a “new world modernity” (Lowe 80). While the burden of this modern rests on a class of English-educated colonized subjects, it works necessarily by constructing new/newly adapted racial others – in Ghanada’s tales these positions are occupied by the Chinese, Indigenous Africans, and Global South demographic groups.

Lowe’s chapter can provide a long historical backdrop for the two short stories (can be paired with mapping assignment 5.1 – especially since many of the verbal maps were constructed from descriptions in the National Geographic), and the stories themselves can extend and complicate Lowe’ argument by providing a case study of imagined inter-racial relations by a South Asian writer at the moment of active political decolonization and the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement. On the other hand, they can be read as parallel histories of rising neo-imperialist sentiment in the postcolonial nation states.

Discussion Questions

- Analyze descriptions of Ghanada’s physique. How does this description both reaffirm and challenge racialized constructs of Indian/Bengali/South Asian masculinity?

- How would you characterize Ghanada’s assessments of white Europeans versus Black Africans? How would you characterize his description of Mr. Nishimara in relation to racial stereotyping?

- How does the text use the language of racialized description to create new political possibilities for South Asians? What kind of South Asians do these possibilities include or exclude?

- What kind of commodities – clothes, technology, weaponry – are fetishized in these texts? What kinds of texts/textual constructs (characters, spaces, trajectories) are preferred over others in your opinion?

- Here is a public resource tracking the history of the illustrations from Ghanada. Discuss the visual pattern/choices of individual illustrators as well as what that tells you about Bengali print culture (which is shaped by empire).

- Compare the illustrations of characters in the text to popular racialized imagery from the nineteenth-century. What are some important connections/transformations?

- Premendra Mitra is widely recognized as a writer of speculative fiction. Which elements would you consider speculative and which elements representative of a post-imperial realism?

Suggested Primary Sources

British Colonial Texts Written about Africa (nineteenth century)

- Livingstone, David. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. John Murray, 1857.

-

The manuscript version of Livingstone’s Missionary Travels – with handwritten pages, maps, and extensive revisions – is a great entry point into the laborious textual production of Africa. Livingstone. Ji Eun Lee’s lesson plan on “Colonial Landscapes and Travel Narratives” sketches out the multiple uses of this text in detail. What I add here is how certain scenes described by him become central to the ideology of the imperial romance/adventure narrative: the lion attack (ch. 1), his articulation of mid-century British-Boer relations (ch. 2), the attack of the tsetse fly (ch. 4), missionary activities (ch. 8). A number of these episodes (in ways directly reminiscent of Livingstone’s text) recur in later fiction, demonstrating the cult-like popularity of Missionary Travels in its time.

- Stanley, Henry Morton. Through the Dark continent, or, The Sources of the Nile: Around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and Down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean. Vol. 1 & 2. Sampson Lowe, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1878.

-

Stanley’s expedition to Africa opens itself to considering a different set of cultural and textual problems than Livingstone’s, particularly around cultural imagery. As a media-conscious journalist, Stanley was much more concerned with marketing his expeditions to a transatlantic audience (as is evident through the publication history of his texts and his career in writing novels). Koivunen gives a detailed account of the technical (visual) equipment that was part of Stanley’s expedition and the material history of how his books were illustrated. Paired with this source, Stanley’s illustrations, descriptions, and maps offer a detailed glimpse into an extremely popular work and magisterial on Africa that the Victorian audience were deeply familiar with.

- Ker, David. Lost Among White Africans: A Boy's Adventures on the Upper Congo. Cassell and Company, 1886.

-

Ker’s novel is an interesting example of the popular print culture about Africa that derives its information directly from well-known travelogs. Published by Cassell and Company exactly one year before the release of King Solomon’s Mines, this book rehearsed elements of Stanley’s expeditions for young audiences. The novel opens with “two young colonists” listening with excitement to the tales of their uncle, Robert Goodman.

The boys travel to the Congo and encounter the traditional conflicts with wild animals and violent encounters with Indigenous communities central to the travelogue genre, but these incidents are articulated in a casual and entertaining way, expressing the author’s lack of first-hand experience unlike Stanley himself or Henry Rider Haggard for example. Another detail that makes the text significant (and makes possible comparative readings) is the fact that Walter Paget, the original illustrator of King Solomon’s Mines is also the illustrator for this text.

- Haggard, Henry Rider. King Solomon’s Mines. 1885. Penguin Classics, 2008.

-

Haggard’s novel combines a deep understanding of the practical experience of life and politics in Southern Africa with an experience of mysticism he associates with the continent. Placing King Solomon’s Mines in conversation with the popular print culture reveals exactly how conscious the text is about print conventions familiar to the audience (a productive pairing is with Stanley or Ker; secondary text with Achebe, Free, Chrisman, Poon).

Speaking to the tradition of colonial travel writing, the text uses fictitious maps and location markers, replicates the typical episodes of travel narratives (travel in a ship to a port; hunting expeditions, encounter with relatively isolated Indigenous nations; illness, disease, and starvation; discussion of ancient ruins; discovery of valuable resources), and uses characterization to convey his analysis of the political events in Southern Africa.

Retellings of Colonial Genres from Africa (nineteenth and twentieth centuries)

- Horton, James B. Africanus. West African Countries and Peoples. J. Johnson, 1868.

-

Pairing particularly well with any travelogue by Stanley or Burton, Horton’s narrative explicitly critiques and challenges colonialist descriptions of Africa. Written in clear and convincing prose, his excoriation of Richard Burton’s racist descriptive techniques offers an important antidote to a limited view of print materials on/from/about Africa. This text would pair particularly well with Achebe’s essays, sketching out a long tradition of critique formulated by Africans that analyze their own misrepresentation. Horton’s considered critiques (and that of other writers) will aid students in avoiding generalizations about “what everyone believed” about Africa and Africans and give them a clearer picture of the vociferous public debates ongoing in the print marketplace.

- Plaatje, Solomon T. P. S. King & Son, 1916.

-

Mhudi is a novel that Plaatje himself describes as a response to the “Zulu romances” of H.R. Haggard, particularly a novel like Nada the Lily. It offers a revisionist history of the era of Mzilikazi of Matabeleland through the love-story of Mhudi and Ra-Thaga. Through this narrative, Plaatje establishes his authority as a cultural commentator who challenges the oppressive historiography of Southern Africa. The prefatory materials to Plaatje’s “Native Life in South Africa” (not included in this module) could also be added to this discussion since it addresses debates about authorship and literary status available to Black South African men.

Bengali Impressions of the “Dark Continent” (twentieth century)

- Bandhyopadhyay, Bibhutibhusan. The Mountains of the Moon. 1936. Translated by Santanu Sinha Chaudhuri. Niyogi Books, 2003.

-

The novel weaves the imperial romance’s typical search for diamonds into Africa into an exploration of coolie or indentured labor migration. Shankar, a Brahmin boy, takes up a position in the Ugandan Railways as a worker to escape his deadening future as a menial clerk in Bengal and remakes himself in the image of the colonial adventurer. His racial identity, however, makes it complicated for him to ascend to the status of the colonial explorer, and he attaches himself to a powerful ally, the Portuguese Diego Alvarez, to acquire status through white proximity. Students can track the text’s reworkings of H. R. Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, particularly through plot elements like the Portuguese prospector, the treasure map, the diamonds in the cave, and the several near-death experiences the travelers face. They can also examine the ways in which Shankar forms attachments with white/white-passing figures to distance himself from the Black Indigenous groups who are original custodians of the land and its resources.

- Mitra, Premendra. “Mosquito” and “Glass” in Mosquito and Other Stories. 1950. Translated by Amlan Das Gupta. Penguin, 2009.

-

These short stories explore a Bengali explorer’s adventure narrative across colonial geographies a “tall tale” or exaggerated anecdote shared between members of a men’s’ boarding house (messbari) in post-war Calcutta. Ghana-da, the explorer, traverses every corner of the globe, but in these two stories his destinations are the Sakhalin Islands and Angola, both places where he goes in search of advanced weapons for international warfare. Students can discuss the interaction between tropes from famous Victorian travelogues by Livingstone, Stanley, and Burton and the material traces of modern politics – railway systems, Nazism, and the Uranium trade – that structure the journeys. They can also discuss how the novel denies the history of South Asian labor migration in the Indian Ocean through Ghanada, who is constantly figured as a gentlemanly character. The complexly racialized figure of Ghanada becomes an Indian “superman” constantly placed in opposition to indentured laborers and Indigenous “junglees” or “savages” to make space for a superior role for the South Asian masculine subject.

Critcal Frameworks

Framing Conversations

- Banerjee, Sukanya. “Transimperial.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 46, no. 3-4, 2018, pp. 925-28.

-

This brief and versatile essay offers a productive frame for a module that examines the differences as much as the similarities between iterations of connected genres – travel/adventure/romance – across a range of colonial/Indian ocean landscapes. Particularly significant is the idea of “what has not been so readily mobile” across empire’s locales, which offers a useful launchpad for conversations on the remaking of colonial narrative paradigms.

- Banerjee, Sukanya, et al. “Introduction: Widening the Nineteenth Century.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 49, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-26

-

The role of this essay is to make the explicit purpose of this module’s design visible to the students. The call to “widen” the nineteenth-century in 2021 was certainly one that energized interdisciplinary scholars; it created opportunities to reframe periodization and put a new collection of major and minor works in productive relation. Students can discuss how this module in particular participates in that goal through the explicit aim of foregrounding “geotemporal linkages” that have become submerged over time.

Theories of Imperial Travel Genres

- Chrisman, Laura. Rereading the Imperial Romance: British Imperialism and South African Resistance in Haggard, Schreiner, and Plaatje. Clarendon Press, 2000.

-

Framing the development of elements of the imperial romance genre in context of the evolving sociopolitical history of Southern Africa, Chrisman’s book offers a deep dive into the practical conditions that informed the representation of Africa in “romances.” It can be added to 3a or used as a background resource for any fictional primary text on Southern Africa.

- Free, Melissa. Beyond Gold and Diamonds: Genre, the Authorial Informant, and the British South African Novel. SUNY Press, 2021.

-

Free develops the concept of the “authorial informant” to reframe the role of writers like H.R. Haggard, Olive Schreiner and others who straddle the British/Southern African traditions. Her reading of Haggard’s “female colonial romances” might fill one of the most significant gaps of this module – the participation of white European women in the colonizer’s role.

- Howell, Jessica. Exploring Victorian Travel Literature Disease, Race and Climate. Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

-

Howell’s concept of “disease environments” (an extension of Mary Louise Pratt’s “contact zone”) is an excellent way to introduce the gradual creation of racialized geographies through textual strategies. Her focus on medical rhetoric, for example, may be particularly useful in exploring Livingstone’s interest in illnesses and infectants, while also offering a lens to look at the psychological malaise that afflicts Haggard’s characters at critical moments of the narrative. Her chapter on Horton’s reworking of colonial pathology is particularly useful for Section 3.2.

Indigenous African Critiques of Colonialism

- Achebe, Chinua. The Education of a British-Protected Child. Knopf/Doubleday, 2008.

-

The essays “Travelling White” and “Africa’s Tarnished Name” explore how European and American intellectuals, much like Conrad, have “an emotional and psychological spell cast on [them] by the long-established and well-heeled tradition of writing about Africa.” Naming this distorting tradition, Achebe’s text presents a clear idea of the impact of this “idea of Africa.”

- Tallie, T.J., Queering Colonial Natal: Indigeneity and the Violence of Belonging in Southern Africa. Duke University Press, 2019.

-

Examining the oppressive homosociality of British administrators and missionaries in describing the masculinity of Indigenous Africans, this book can be a way to introduce students to the ways in which queer studies offers important correctives to the colonial paradigms of representation. An especially productive exercise might be to pair Taille with illustrations from Haggard and Stanley, to analyze the processes of depiction that contribute to a strategically abormalized images of Indigenous peoples.

- Mudimbe, V. Y. The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Indiana University Press, 1988.

-

This influential work by Mudimbe identifies the “model of history” that guides travelers from Mungo Park to anthropologists like Levi-Strauss to engage in a discourse inflected by “Africanism.” Challenging the notion of Africa as an empty space upon which imperialist notions can be imposed, Mudimbe stages the conflict between discourses of primitivism and savagery that targeted Indigenous cultures, and ways to decenter them through revised “methods of knowing.”

- Wainaina, Binyavanga. “How to Write About Africa?” Granta. May 2019.

-

Binyavanga’s tongue-in-cheek yet accurate piece satirizes overused stereotypes of Africa. She mockingly tells us to “treat Africa as one country” in order to highlight common pitfalls affecting Western discourse of Africa from the eighteenth century to the present in a short classroom-friendly piece.

- Faloyin, Dipo. Africa Is Not a Country. W. W. Norton, & Co., 2022.

-

Responding to Binyavanga’s central complaint, Faloyin offers a wealth of narratives about the African continent that opposes the exact framework of imperialist discourse this module is engaged in diagnosing. Faloyin’s narratives of individual spaces, cultures, and lived experiences fill in the gaps that have been created through the tired repetition of stereotypical imagery. The discussion of maps as ideological products can be combined with several texts mentioned here.

- Atkins, Keletso. The Moon is Dead! Give Us Our Money! Heinemann, 1993.

-

A magisterial social history of Indigenous African working class that will offer a counterforce to top-down approaches to the conflicts of class, race, and power in the South African region. It can be paired with Burton’s discussions of the fraught alliances between Indian and African workers in the early twentieth century or any of the lesson plans or research assignments.

Intimacy, Indentureship, and Histories of Contact Across the Global South

- Burton, Antoinette. Africa in the Indian Imagination. Duke University Press, 2016.

-

Despite tentatively framing the uplifting vision of a past where Indians and Africans “undoubtedly worked and played together...fought with and against each other” in a variety of transnational exchanges, Burton’s book focuses primarily on the many dissonances that hinder the formation of a resilient anticolonial bond – critical among them being “colonial-era racial hierarchies.” This text would work as essential background/secondary reading for the sources in 2b.

- Hofmeyr, Isabel. Gandhi’s Printing Press: Experiments in Slow Reading. Harvard University Press, 2013.

-

Hoftmeyr’s chapter on the print cultures of the Indian Ocean world (ch. 1) do the valuable work of swiftly sketching an intercontinental architecture of print networks for students. The chapter fleshes out the relationship between print media and space through concepts like “diasporic printing” and “print frontiers” – thus offering a paradigm to question the widespread distribution and circulation of a mythicized African continent.

- Carter, Marina and Khal Torabully. Coolitude: An Anthology of Indian Labor Diaspora. Anthem Press, 2002.

-

Framing the identity of the “coolie” in a genealogy of terms including négritude and créolité, the Coolitude anthology focuses on coolie’s cultural production, a genre that could presumably include Shankar’s travelogue, and would bear a deeply contentious relation to Ghanada’s stories. Some of the stories of misled migrants in the early pages of the anthology echoes the bright hopes that Shankar’s uncle told him during recruitment, although the position clearly did not fit Shankar’s interests. The text also places migration into South Africa within a larger panorama of South Asian indentured migration to British colonies worldwide.

- Lowe, Lisa. The Intimacies of Four Continents. Duke University Press, 2016.

-

A byword for influential and deeply careful global study, Lisa Lowe’s The Intimacies could be meaningfully placed in any part of this module but especially paired with texts in 2c. In conversation with Burton (2016) for example, her idea of intercontinental alliances and relations between people of color can offer a critical counterpoint to the fraught relations between immigrant South Asian and Indigenous African people in the Bengali narratives included here.

- Mowtushi, Mahruba T. Africa in the Bengali Imagination:From Calcutta to Kampala, 1928-1973. Taylor & Francis, 2022.

-

This monograph is a valuable resource for contextualizing the Bengali language primary texts and their unfolding against the background of transnational connections between Africa and India. Most importantly, they would ground students in the role of these texts in a Bengali literary/cultural milieu, emphasizing their participation in regional and transimperial literary traditions.

- Islam, Najnin. “Life Unadministered: Colonial Care and the Indian Care” Small Axe, vol. 27 no. 1, March 2023, pp. 1-18.

-

This recent article employs the concept of “care” to demonstrate the ways in which racialized labor was subjected to soft forms of management and control. Since it focuses on a historical voyage from Calcutta to the Caribbean, it can both make students aware of the historical contexts of the actual journey across the Indian Ocean faced by indentured laborers, and the close connection between the Caribbean and Africa in practices of indentureship and its maintenance.

- Banerjee, S. and Basu, S. “Mountain of the Moon: Africa and the Gendered Imagining of Modern India.” Gender & History, vol. 27, 2023, pp. 171-189.

-

This important article highlights the aspect of imperial masculinity that is a critical framework to understand the affective construction of Africa in imperial texts. It is a perfect complement to the lesson plans in Section 2, since it will allow students to identify the Bengali imperialist figures within existing logics of “proper manhood” among colonial subjects as a response to accepted forms of English manliness.

- Sengupta, Oishani. “The Brown Adventure Romance: Chander Pahar and the Management of Racial Capital.” Verge: Studies in Global Asias, 2024. (Forthcoming)

-

This article was written in conjunction with the research done to produce this lesson module and can form a natural pairing when read alongside it. In particular, it can be read with Section 2.1 (lesson plan) since it explores many of the questions related to Shankar’s remaking as an imperialist adventurer who is, paradoxically, racialized as brown.

- Lewis, Su Lin and Carolien Stolte. "Other Bandungs: Afro-Asian Internationalisms in the Early Cold War." Journal of World History, vol. 30 no. 1, p. 1-19, 2019.

-

The purpose of this article is to give students a wider view of Afro-Asian contact beyond the dominant narrative of the Bandung Conference. While the article’s focus on “disrupt[ing] hard divisions between state and non-state and warring Cold War blocs” might seem a little distant from the concerns of its volume, it can affirm to students that grand narratives of intercontinental alliance are rife with slippage and untold histories.

Multimodal Assignments

Mapping Assignment

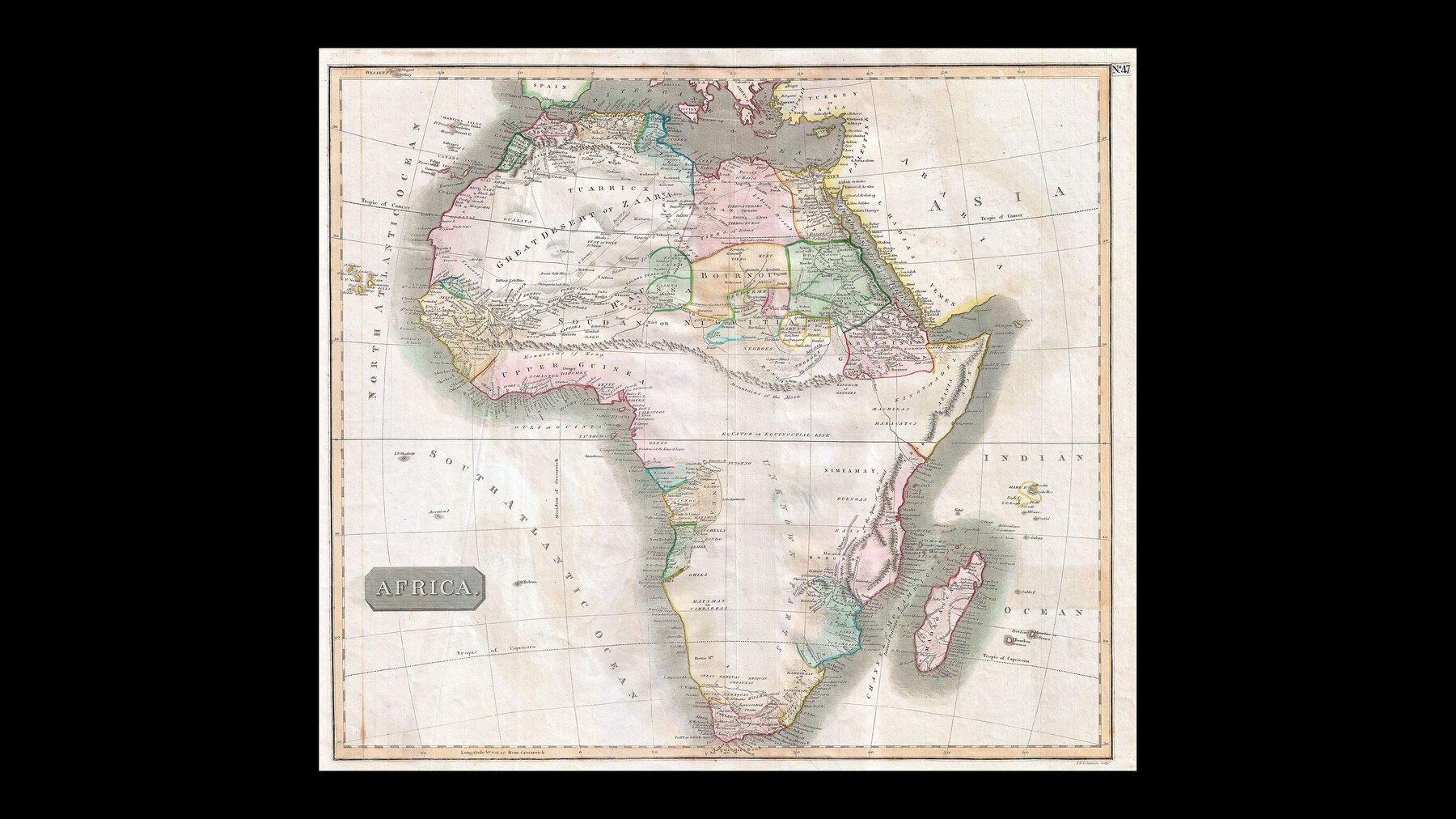

Since these primary texts contain racialized geographies that are produced from a relationship between imperial print culture and the imagination, one simple mapping assignment might be to compare three maps of African territories:

- An early hand-drawn/published map by a European explorer

- A twentieth-century map of the region

- A fictional map (either verbal or visual)

Edward Said’s concept of “imaginary geographies” (Orientalism) and Matthew H. Edney’s concept of “framing” colonized space may assist students with articulating the strategic differences of mapping used in each of the three objects.

Step 1: The assignment can start from the idea that maps are layered, so Map 1 led to the creation of Map 2 and Map 3; in some cases, both Map 1 and Map 2 lead to the creation of Map 3.

Step 2: Interrogating and historicizing the clearly inaccurate maps will lead to a more critical engagement with the history of mapping itself.

Step 3: Finally, the class will approach the goal of defamiliarizing the “contemporary map” as a product of fiction, politics, and power deeply shaped by imperial technologies and fantasies.

Step 4: This critique of maps of Africa could be articulated visually as slides or a Story Map that demonstrates the political decision-making that impacted the process of marking colonial space.

Archival Assignment

Archival assignments in the classroom serve to familiarize students with the material aspects of these texts. An example of such an assignment that can be completed in class is one pairing Mountains of the Moon with articles from Indian Opinion, the activist pamphlet published by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa to agitate on because of South Asians’ political rights. Hofmeyr’s chapter situating the physical context of the pamphlet’s publication (ch. 3) and Carter and Torabully’s discussion of indentured workers becoming “international proletarians” (ch, 2; 2002) can provide framing material for the exercise.

Step 1: Select an early volume of Indian opinion, for example Vol. 5.

Step 2: Students can spend some time in larger groups discussing the structure and framework of the volume. There could be broad guiding questions about print production, typography, images, multilingualism, materiality, etc. to situate their explorations.

Step 3: Each student should pick 3 items connecting the same rough topic – it could be 2 advertisements and 1 article about bicycle sales for instance. They could triangulate these three sources, use their own research skills, and craft a brief glimpse of life viewed from the perspective of Indians in South Africa in the early twentieth century.

Step 4: They could place this narrative in conversation with any of the primary/secondary text in this module to frame their discovery within a larger context of exploring indentureship, migration, and racialized labor in empire.

Developer Biography

Oishani Sengupta is an assistant professor of English at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her work explores the role of colonial visual print culture in shaping race-making in the transatlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. Her work has appeared in Criticism and Verge: Studies in Global Asias, and Modernism/modernity Print+. Her first book tentatively titled Dark Empire: Racializing Africa in Indian Ocean Print Cultures is currently in progress and directly related to the work reproduced in this cluster.Tile/Header Image Caption

Thomson, John. Africa. 1813. Geographicus. This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art.

Page/Lesson Plan Citation (MLA)

Oishani Sengupta, dev. “Colonial/Postcolonial Texts of the “Dark Continent.” Barbara Barrow, Renée Fox, Cherrie Kwok, Diana Rose Newby, Matthew Poland, Jessie Reeder, and Emma Soberano, collab. peer revs.; Ryan D. Fong, les. plan clust. dev./copyed. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2024, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/lesson_plans/contemporary_postcolonial_texts.html.